WawonaNews.com - November 2018

‘Entering Burn Area’: Yosemite After the Fire

America’s national parks are increasingly bearing the burden of climate change, as rising temperatures and new weather patterns create mega blazes. A report from the burn zone.

By Bonnie Tsui, NYT

A megafire is a fire that consumes more than 100,000 acres.

A few months ago, in an area near Yosemite National Park, the Ferguson fire raged through the Sierra Nevada mountains, burning 86,000 acres of forest before jumping Highway 41 into the park and scorching another 11,000 acres within its boundaries — not technically a megafire, but just shy of it.

Three thousand people from around the world were dispatched to help fight the blaze, which choked the valley in an impenetrable wall of smoke; two firefighters died. For three weeks during peak season, one of the most popular national parks in the country was closed to the public.

A friend of mine went camping in Yosemite a few weeks after the park reopened. During the day, she and her husband and children passed controlled burns and set up camp amid the stunning autumn colors of Tuolumne Meadows. She awoke in the middle of the night to strangely warm, high winds whipping her family’s tent, and felt something she hadn’t felt before: fear.

“Is this what it is to camp in California in the 21st century?” she asked me.

In early October, I went to experience the tactile reality of Yosemite after the fires for myself.

- Nov. 5, 2018

A megafire is a fire that consumes more than 100,000 acres.

A few months ago, in an area near Yosemite National Park, the Ferguson fire raged through the Sierra Nevada mountains, burning 86,000 acres of forest before jumping Highway 41 into the park and scorching another 11,000 acres within its boundaries — not technically a megafire, but just shy of it.

Three thousand people from around the world were dispatched to help fight the blaze, which choked the valley in an impenetrable wall of smoke; two firefighters died. For three weeks during peak season, one of the most popular national parks in the country was closed to the public.

A friend of mine went camping in Yosemite a few weeks after the park reopened. During the day, she and her husband and children passed controlled burns and set up camp amid the stunning autumn colors of Tuolumne Meadows. She awoke in the middle of the night to strangely warm, high winds whipping her family’s tent, and felt something she hadn’t felt before: fear.

“Is this what it is to camp in California in the 21st century?” she asked me.

In early October, I went to experience the tactile reality of Yosemite after the fires for myself.

At the edge of Glacier Point’s 3,200-foot cliff, one of the most iconic places in Yosemite, the absurd daylight grandeur of Half Dome and the forested slopes exert their solemn gravity.

In the face of this holy beauty, your jadedness falls away. You look and look, and look some more. You find you cannot look enough. Wait another quiet moment or two, and you see that this cliff is, in fact, a place of pilgrimage. You see people from all over the world; you listen to them speak a dozen different languages; you watch them gently touch a gnarled tree, a wall of granite. Something like grace remains.

This is where my friend Lynsay and I began our day hike on the sun-dappled Panorama Trail toward Nevada Fall, a round-trip, 10.5-mile hike that would take us a little over five hours to complete. We chose this trail for its larger, longer view on what fire means to a place like Yosemite — not just the most recent fire, but the constant, successive waves of fire that play a vital role in shaping and maintaining the health of a forest.

The drive up the switchbacked, 16-mile road leading to the Glacier Point trailhead, off Highway 41 out of the more-visited Yosemite Valley, is itself a kind of reverse visual timeline of the park’s recent fire history.

In the face of this holy beauty, your jadedness falls away. You look and look, and look some more. You find you cannot look enough. Wait another quiet moment or two, and you see that this cliff is, in fact, a place of pilgrimage. You see people from all over the world; you listen to them speak a dozen different languages; you watch them gently touch a gnarled tree, a wall of granite. Something like grace remains.

This is where my friend Lynsay and I began our day hike on the sun-dappled Panorama Trail toward Nevada Fall, a round-trip, 10.5-mile hike that would take us a little over five hours to complete. We chose this trail for its larger, longer view on what fire means to a place like Yosemite — not just the most recent fire, but the constant, successive waves of fire that play a vital role in shaping and maintaining the health of a forest.

The drive up the switchbacked, 16-mile road leading to the Glacier Point trailhead, off Highway 41 out of the more-visited Yosemite Valley, is itself a kind of reverse visual timeline of the park’s recent fire history.

Near the Glacier Point turnoff, we passed coal-black trees lined up like scarecrows on the side of the road, arms raised in supplication, and dark umber burn scars so fresh from the Ferguson fire that they still smelled of smoke, even through the car windows. Hastily chopped trees betrayed firefighting efforts to create fire breaks in the middle of the night. Climbing higher in elevation, we left Ferguson’s burn footprint behind, but as we passed Mono Meadow, we spotted healthy fir trees with lightly charred lower trunks — signs of a fast-moving brush fire that had left the canopies intact. These swaths of forest were burned by 2017’s Empire fire, caused by a lightning strike, and several other blazes over the last decade.

As we hitched up our day packs and headed down the first mile of the Panorama Trail on foot, we admired the fall palette of cinnamon, rust, citron and lime. Newly attuned to the little clues that the forest offers, we saw evidence of other, older fires almost immediately. Tree trunks were blistered and split from intense heat — the mottled pattern reminiscent of Dutch crunch bread — but there they were, still standing, with a lush carpet of verdant shrubs and other undergrowth filling in around their feet.

After crossing a wooden bridge over Illilouette Creek and a steep climb — 700 feet in elevation over 1.5 miles — to an exposed ridgeline, we descended again, and the microclimate shifted to upper montane forest: cooler, shadier and greener, with red fir, pine and juniper trees, some of them furry with electric-green moss. We began to see the patchwork way that fire ideally works in a big forest — different areas burn at different times, using up available fuels. In effect, this helps contain flames when subsequent fires do come through, giving older burned areas time to recover. Think of a farmer rotating crops.

As we hitched up our day packs and headed down the first mile of the Panorama Trail on foot, we admired the fall palette of cinnamon, rust, citron and lime. Newly attuned to the little clues that the forest offers, we saw evidence of other, older fires almost immediately. Tree trunks were blistered and split from intense heat — the mottled pattern reminiscent of Dutch crunch bread — but there they were, still standing, with a lush carpet of verdant shrubs and other undergrowth filling in around their feet.

After crossing a wooden bridge over Illilouette Creek and a steep climb — 700 feet in elevation over 1.5 miles — to an exposed ridgeline, we descended again, and the microclimate shifted to upper montane forest: cooler, shadier and greener, with red fir, pine and juniper trees, some of them furry with electric-green moss. We began to see the patchwork way that fire ideally works in a big forest — different areas burn at different times, using up available fuels. In effect, this helps contain flames when subsequent fires do come through, giving older burned areas time to recover. Think of a farmer rotating crops.

A mile before the 594-foot Nevada Fall, we began to hear the audible rush of water, and glimpsed Half Dome and Liberty Cap through the canopy. Here, too, were fire scars. As scars do on our own bodies, these tell a story of destruction, and renewal.

Yosemite became a national park 128 years ago. “For the people who manage the park, the impacts of climate change are ongoing,” Scott Gediman, a veteran ranger and public affairs officer who has been working in Yosemite for more than two decades, told me. After a century of fire suppression, during which forests got denser and accumulated woody debris led to hotter, more catastrophic infernos, fire chiefs in Yosemite and elsewhere have come to embrace periodic burns as good wilderness management.

“The Ferguson fire, from where it started and moved toward the park, it was slow moving. When it actually entered the park, a lot of areas had had previously prescribed fires, so it didn’t burn as hot, and it wasn’t as devastating as it could have been,” Mr. Gediman said. “That’s ultimately what we want.”

At the completion of the day’s hike, after our return to Glacier Point, Lynsay and I drove back to Highway 41 and headed south toward Fish Camp. By now, we’d seen plenty of fire traces around the park — in the burn piles in the valley, in the signs saying “Entering Burn Area, Watch Out For Rock Fall.” But this is where we would see the most dramatic views of all: vast tracts of blackened forest on the downhill side of 41, remnants of red fire retardant still lingering on trees on the uphill side, the road having served as a fire break for embattled firefighters struggling to contain the flames below.

We pulled over at one turnoff and walked down into the woods for a closer examination. Rustling leaves, felled trees, the faint scent of smoke, the burned and broken remains of a curious glass bottle stamped with the word “CONTENTS.” And, in the middle of this devastation, bright little shoots sprouting up, doing what grass does — grow, of course, cheerfully and obliviously.

Yosemite became a national park 128 years ago. “For the people who manage the park, the impacts of climate change are ongoing,” Scott Gediman, a veteran ranger and public affairs officer who has been working in Yosemite for more than two decades, told me. After a century of fire suppression, during which forests got denser and accumulated woody debris led to hotter, more catastrophic infernos, fire chiefs in Yosemite and elsewhere have come to embrace periodic burns as good wilderness management.

“The Ferguson fire, from where it started and moved toward the park, it was slow moving. When it actually entered the park, a lot of areas had had previously prescribed fires, so it didn’t burn as hot, and it wasn’t as devastating as it could have been,” Mr. Gediman said. “That’s ultimately what we want.”

At the completion of the day’s hike, after our return to Glacier Point, Lynsay and I drove back to Highway 41 and headed south toward Fish Camp. By now, we’d seen plenty of fire traces around the park — in the burn piles in the valley, in the signs saying “Entering Burn Area, Watch Out For Rock Fall.” But this is where we would see the most dramatic views of all: vast tracts of blackened forest on the downhill side of 41, remnants of red fire retardant still lingering on trees on the uphill side, the road having served as a fire break for embattled firefighters struggling to contain the flames below.

We pulled over at one turnoff and walked down into the woods for a closer examination. Rustling leaves, felled trees, the faint scent of smoke, the burned and broken remains of a curious glass bottle stamped with the word “CONTENTS.” And, in the middle of this devastation, bright little shoots sprouting up, doing what grass does — grow, of course, cheerfully and obliviously.

The next morning, Lynsay and I hiked the new trails at Mariposa Grove, a huge cathedral of giant sequoias 250 to 300 feet high, with some trees as old as 3,000 years. In June, the grove reopened to the public after three years of restoration work. Giant sequoias are fire-resistant, which helps explain their longevity, and depend on fire to reproduce: the fire clears away undergrowth and helps to disperse seed cones into mineral-rich soil. Within the park, prescribed fire is one part of maintaining the health of these ancient giants.

The grove’s restoration — as well as the current fire management plan for Yosemite — was designed in consultation with affiliated American Indian tribes and Native American groups. In the centuries long before European visitors arrived, native populations in Yosemite Valley used controlled burning and other tools to manage the living landscape on which they depended.

Trees, it turns out, have a heartbeat. I read this in a scientific journal, in an article about a new study showing that trees exhibit a periodic pulse, a result of their pumping water throughout the day and night. They do it so slowly that it is virtually undetectable to the human eye.

It’s an intriguing, romantic bit of poetry, more literary conceit than literal fact. But it got me thinking about our complex and emotional human relationship with the wilderness.

The grove’s restoration — as well as the current fire management plan for Yosemite — was designed in consultation with affiliated American Indian tribes and Native American groups. In the centuries long before European visitors arrived, native populations in Yosemite Valley used controlled burning and other tools to manage the living landscape on which they depended.

Trees, it turns out, have a heartbeat. I read this in a scientific journal, in an article about a new study showing that trees exhibit a periodic pulse, a result of their pumping water throughout the day and night. They do it so slowly that it is virtually undetectable to the human eye.

It’s an intriguing, romantic bit of poetry, more literary conceit than literal fact. But it got me thinking about our complex and emotional human relationship with the wilderness.

This summer, soon after the evacuation order for Yosemite was lifted, an anonymous ranger posted a heartfelt reflection on the park’s website. The writer spoke of feeling separation anxiety from the park, a yearning to return, and expressed a surprisingly poignant view of being a park ranger: “A spark emits from a visitor, a moment when one transcends the physical elements of a place and makes an emotional, sometimes spiritual, connection to place. As an interpreter, I am constantly chasing that moment and, regardless of the fire, I couldn’t give up the opportunity to facilitate the formation of those sparks. I wasn’t willing to let my relationship with Yosemite fade away.”Is it weird that I have a framed photo of John Muir and Teddy Roosevelt hanging in my bedroom?

Taken in 1903, it is a quintessential image of the two men at Glacier Point during a three-day wilderness trip into Yosemite. The first night, they camped at Mariposa Grove.

“No temple made with human hands can compete with Yosemite,” wrote Muir. His advocacy is what led to the creation of this national park in 1890.

Roosevelt himself said this in a 1915 appreciation of Muir: “He was a great factor in influencing the thought of California and the thought of the entire country so as to secure the preservation of those great natural phenomena — wonderful canyons, giant trees, slopes of flower-spangled hillsides.”

Taken in 1903, it is a quintessential image of the two men at Glacier Point during a three-day wilderness trip into Yosemite. The first night, they camped at Mariposa Grove.

“No temple made with human hands can compete with Yosemite,” wrote Muir. His advocacy is what led to the creation of this national park in 1890.

Roosevelt himself said this in a 1915 appreciation of Muir: “He was a great factor in influencing the thought of California and the thought of the entire country so as to secure the preservation of those great natural phenomena — wonderful canyons, giant trees, slopes of flower-spangled hillsides.”

Our national parks are bearing a disproportionate burden of climate change. By virtue of location — high-altitude, high-latitude regions warm more quickly, and arid areas across the West have been seeing record low rainfall — national parklands are getting hotter and drier twice as fast as the rest of the country, according to a new study by climate scientists at the University of California, Berkeley.

The truth is that the Yosemite Valley of today is not the same place it was a century ago. One hundred years from now, because of increased warming trends, it may well be unrecognizable.

After all, the way we use the park is changing, too. My friend Sarah told me recently about something called the firefall, a massive bonfire of burning logs shoveled off Glacier Point’s ledge into the inky nighttime darkness, a stupendously popular tradition that began in 1872.

Her family has been in California for generations, and she grew up backpacking in Yosemite. She recalls her dad’s tales of the nightly spectacle with wonder and skepticism. Real fire! Shoveled off a cliff into the wilderness! What would Smokey Bear say? We Google “Yosemite” and “fire” and “cliff,” and, in short order, we find ourselves exclaiming over a blurry archival video from the 1960s.

It is astounding to think that they did this and the whole place didn’t go up in flames. The National Park Service finally banned the practice in 1968, and a few years later, people noticed that a waterfall on the eastern side of El Capitan created the same fiery effect for a few weeks in February, when the winter light hit the font of melting snowpack just right. The fame of this illusory firefall has since eclipsed that of the old one, but I can’t stop thinking of the original firefall — the one made out of real fire.

Here’s another definition of firefall, this time from Merriam-Webster: “a tree whose fall is caused by the partial destruction of its roots in a ground fire.”

The truth is that the Yosemite Valley of today is not the same place it was a century ago. One hundred years from now, because of increased warming trends, it may well be unrecognizable.

After all, the way we use the park is changing, too. My friend Sarah told me recently about something called the firefall, a massive bonfire of burning logs shoveled off Glacier Point’s ledge into the inky nighttime darkness, a stupendously popular tradition that began in 1872.

Her family has been in California for generations, and she grew up backpacking in Yosemite. She recalls her dad’s tales of the nightly spectacle with wonder and skepticism. Real fire! Shoveled off a cliff into the wilderness! What would Smokey Bear say? We Google “Yosemite” and “fire” and “cliff,” and, in short order, we find ourselves exclaiming over a blurry archival video from the 1960s.

It is astounding to think that they did this and the whole place didn’t go up in flames. The National Park Service finally banned the practice in 1968, and a few years later, people noticed that a waterfall on the eastern side of El Capitan created the same fiery effect for a few weeks in February, when the winter light hit the font of melting snowpack just right. The fame of this illusory firefall has since eclipsed that of the old one, but I can’t stop thinking of the original firefall — the one made out of real fire.

Here’s another definition of firefall, this time from Merriam-Webster: “a tree whose fall is caused by the partial destruction of its roots in a ground fire.”

The one hits uncomfortably close to home. Attitudes toward fire and fire dangers are evolving, but we are still cavalier in our own ways. As we build lives deeper and deeper into every corner of the wild, we are increasingly vulnerable to fire’s fiercely destructive power, the way it behaves in ways we don’t completely understand. It is a given that fire management in these places will become ever more challenging, with a human cost.

For now, nature continues to endure. What did we see, post-fire? That resilience and rebirth can still be found. In the tiny green ferns shyly unfurling in the enriched earth. In the naturalization ceremony held at Glacier Point for 43 of the country’s newest citizens, just a month after the park reopened. In the multiagency crews working diligently to clear remaining fire hazards, and to seed and shore up eroding hillsides. In the rangers welcoming returning visitors, in the full campgrounds, in the climbers walking along the trails in the glorious late-afternoon light, their carabiners clinking a musical accompaniment on the approach to the great walls of granite.

Bonnie Tsui is a writer based in Berkeley, Calif. Her next book, “Why We Swim,” will be published by Algonquin Books in March 2020.

Selfie appears to show woman before she and husband fell to deaths at Taft Point

CBS News SAN JOSE – An East Bay man who was recently visiting Yosemite National Park was shocked to discover he might have taken the last known photo of the woman who died with her husband after a horrific fall from the park's popular Taft Point last week. The couple – Vishnu Viswanath and his wife Meenakshi Moorthy — were popular travel bloggers who recently moved to San Jose and loved to explore the world.

CBS San Francisco found a man who may have been one of the last people to see the couple alive.

When Oakland resident Sean Matteson snapped a selfie just feet from Taft Point, he had no idea it may have been moments

before Moorthy and Viswanath plunged to their death. Moorthy can be seen behind Matteson's shoulder, her distinctive dyed pink hair plainly visible in the photo.

"It gave me goosebumps to be honest," said Matteson. "I got the chills. It was very eerie."

Park rangers recovered the bodies of the couple last Thursday about 800 feet below Taft Point after hikers spotted them the day before.

Matteson said his selfie was taken on Sunday just after 5 p.m.

"It seemed like a lot of stories out there, of speculation of when and how and all this stuff," explained Matteson. "And I guess we just felt that it was incumbent upon us to share our impression of that day and the fact that we saw her in person."

Matteson said Moorthy appeared to enjoy the scenery from the popular view point. The 30-year-old was no stranger to the risk she was taking.

Moorthy and her husband had posted risky photos on their popular travel blog.

Just this past spring, she posted a picture of herself at the Grand Canyon that acknowledge the danger. The caption of the photo read, "A lot of us including yours truly is a fan of daredevilry attempts of standing at the edge of cliffs. But did you know that wind gusts can be fatal? Is our life worth one photo?"

Matteson said he saw Moorthy standing on a lower ledge closer to the edge than he and his girlfriend were standing.

"But yeah, no railings. I mean, it's very treacherous out there," said Matteson. "It could be very easy to make one wrong step and be in trouble."

Moorthy's husband Viswanath worked for Cisco. They were new to California, having relocated recently from New York.

On her travel blog, Moorthy wrote "live every moment" and called her husband "an amazing guy."

"Nothing seemed like anything was wrong or anything like that," remembered Matteson. "It seemed like they were there doing what they loved to do. That was my impression."

CBS San Francisco reached out to Cisco, which released the following statement: "It is with great sadness that we learned of the passing of a Cisco employee, Vishnu Viswanath. As always, we will pull together to extend our support to the employee's family and our fellow colleagues during this difficult time."

CBS News SAN JOSE – An East Bay man who was recently visiting Yosemite National Park was shocked to discover he might have taken the last known photo of the woman who died with her husband after a horrific fall from the park's popular Taft Point last week. The couple – Vishnu Viswanath and his wife Meenakshi Moorthy — were popular travel bloggers who recently moved to San Jose and loved to explore the world.

CBS San Francisco found a man who may have been one of the last people to see the couple alive.

When Oakland resident Sean Matteson snapped a selfie just feet from Taft Point, he had no idea it may have been moments

before Moorthy and Viswanath plunged to their death. Moorthy can be seen behind Matteson's shoulder, her distinctive dyed pink hair plainly visible in the photo.

"It gave me goosebumps to be honest," said Matteson. "I got the chills. It was very eerie."

Park rangers recovered the bodies of the couple last Thursday about 800 feet below Taft Point after hikers spotted them the day before.

Matteson said his selfie was taken on Sunday just after 5 p.m.

"It seemed like a lot of stories out there, of speculation of when and how and all this stuff," explained Matteson. "And I guess we just felt that it was incumbent upon us to share our impression of that day and the fact that we saw her in person."

Matteson said Moorthy appeared to enjoy the scenery from the popular view point. The 30-year-old was no stranger to the risk she was taking.

Moorthy and her husband had posted risky photos on their popular travel blog.

Just this past spring, she posted a picture of herself at the Grand Canyon that acknowledge the danger. The caption of the photo read, "A lot of us including yours truly is a fan of daredevilry attempts of standing at the edge of cliffs. But did you know that wind gusts can be fatal? Is our life worth one photo?"

Matteson said he saw Moorthy standing on a lower ledge closer to the edge than he and his girlfriend were standing.

"But yeah, no railings. I mean, it's very treacherous out there," said Matteson. "It could be very easy to make one wrong step and be in trouble."

Moorthy's husband Viswanath worked for Cisco. They were new to California, having relocated recently from New York.

On her travel blog, Moorthy wrote "live every moment" and called her husband "an amazing guy."

"Nothing seemed like anything was wrong or anything like that," remembered Matteson. "It seemed like they were there doing what they loved to do. That was my impression."

CBS San Francisco reached out to Cisco, which released the following statement: "It is with great sadness that we learned of the passing of a Cisco employee, Vishnu Viswanath. As always, we will pull together to extend our support to the employee's family and our fellow colleagues during this difficult time."

Yosemite engagement mystery solved! Photographer found couple after viral search

(CNN) — The photographer whose photo of an engagement in Yosemite National Parksparked a viral search, says he's found the mystery couple.

Matthew Dippel was getting ready to take a picture of a friend at Yosemite's Taft Pointearlier this month, when he saw a man get on one knee to propose to a woman.

He didn't see any other photographers around, so he snapped a picture of the moment to give to the couple.

Dippel ran over to find them, but they were gone by the time he got there.

"I must have just ran right past their friends that they had up there with them," he said.

Dippel was in the middle of a road trip, but he posted the photo on social media when he got home to Grand Rapids, Michigan on October 17.

The posts were shared thousands of times by people all over the world.

Charlie Bear told HLN that he and his now-fiance Melissa stumbled on the post on Instagram last week.

"At first, I wasn't really sure it was us to be honest," Bear said. But they compared Dippel's photo with pictures they had taken to make sure.

Dippel was a little skeptical, at first, because he'd gotten tons of messages from people claiming to be the couple, so he asked them to prove it.

"They sent me over iPhone screen shots of some of their friends that were up on that point that day, and they are wearing the exact same thing, and the photos are timestamped on the exact same day and the same time that I was there," Dippel said. "It just perfectly matched up to Charlie and Melissa."

Dippel said he's still working out the details to get them a print of the photo.

Bear said that it was actually their second proposal. He'd asked in February, but wanted to something personal, that would be memorable for them.

Mission accomplished.

"Even though this was the second time around I was just as nervous as the first time, and I was even more nervous being high up on the cliff," Bear said. "I have a fear of heights, and I kind of overcame that for her."

They're now planning an April wedding in Malibu, California.

Matthew Dippel was getting ready to take a picture of a friend at Yosemite's Taft Pointearlier this month, when he saw a man get on one knee to propose to a woman.

He didn't see any other photographers around, so he snapped a picture of the moment to give to the couple.

Dippel ran over to find them, but they were gone by the time he got there.

"I must have just ran right past their friends that they had up there with them," he said.

Dippel was in the middle of a road trip, but he posted the photo on social media when he got home to Grand Rapids, Michigan on October 17.

The posts were shared thousands of times by people all over the world.

Charlie Bear told HLN that he and his now-fiance Melissa stumbled on the post on Instagram last week.

"At first, I wasn't really sure it was us to be honest," Bear said. But they compared Dippel's photo with pictures they had taken to make sure.

Dippel was a little skeptical, at first, because he'd gotten tons of messages from people claiming to be the couple, so he asked them to prove it.

"They sent me over iPhone screen shots of some of their friends that were up on that point that day, and they are wearing the exact same thing, and the photos are timestamped on the exact same day and the same time that I was there," Dippel said. "It just perfectly matched up to Charlie and Melissa."

Dippel said he's still working out the details to get them a print of the photo.

Bear said that it was actually their second proposal. He'd asked in February, but wanted to something personal, that would be memorable for them.

Mission accomplished.

"Even though this was the second time around I was just as nervous as the first time, and I was even more nervous being high up on the cliff," Bear said. "I have a fear of heights, and I kind of overcame that for her."

They're now planning an April wedding in Malibu, California.

Maeve Juarez To Be Honored With Valor Award

Oct 25, 2018 at 08:05 PM

The Montecito Fire Department will host a Valor Ceremony to recognize Firefighter Paramedic, Andy Rupp and Wildland Fire Specialist, Maeve Juarez, who worked in Wawona during the Ferguson fire, for their heroic efforts during the Montecito Debris Flow event on January 9, 2018.

The Valor award is the highest honor presented to Montecito Fire Personnel for extraordinary acts of courage involving significant risk of injury or death to the member.

The Ceremony will take place at the Montecito Union School, 385 San Ysidro Road on Tuesday, October 30, at 5:30 p.m.

The public is welcome to attend this special event.

Oct 25, 2018 at 08:05 PM

The Montecito Fire Department will host a Valor Ceremony to recognize Firefighter Paramedic, Andy Rupp and Wildland Fire Specialist, Maeve Juarez, who worked in Wawona during the Ferguson fire, for their heroic efforts during the Montecito Debris Flow event on January 9, 2018.

The Valor award is the highest honor presented to Montecito Fire Personnel for extraordinary acts of courage involving significant risk of injury or death to the member.

The Ceremony will take place at the Montecito Union School, 385 San Ysidro Road on Tuesday, October 30, at 5:30 p.m.

The public is welcome to attend this special event.

Rangers recover bodies of 2 people who fell to their deaths at Taft Point

CBS News- A Yosemite National Park official says park rangers have recovered the bodies of two people who fell to their deaths from a popular overlook. Rangers recovered the bodies of a male and a female on Thursday after working all day to get to them, said Jamie Richards, a park spokesperson.

Richards said she did not know how the rangers reached the bodies but that they worked all day in the "challenging area."

She said officials are investigating when the pair fell and from which part of Taft Point, which is 3,000 feet above the famed Yosemite Valley floor. The victims have not been identified.

The Taft Point overlook has some railings but visitors can walk to the edge of a vertigo-inducing granite ledge that does not have a railing and has become a popular spot for photos posted on social media.

"It's a super-popular place in Yosemite. Really popular for engagements, proposals, weddings," photographer Matt Dippel told CNN. "There were at least three or four different brides and grooms up there doing their post-wedding photos, so it's definitely not an uncommon thing to see up there."

More than 10 people have died at the park this year, six of them from falls and the others from natural causes, park spokesman Scott Gediman said.

Last month, an Israeli teenager fell hundreds of feet to his death while hiking near the top of 600-foot-tall Nevada Fall. The death of 18-year-old Tomer Frankfurter was considered an accident, the Mariposa County coroner's office said.

Taft Point is also where world-famous wingsuit flier Dean Potter and his partner, Graham Hunt, died after leaping from the cliff in 2015. The pair were experienced at flying in wingsuits - the most extreme form of BASE jumping - and crashed after trying to clear a V-shaped notch in a ridgeline.

BASE jumping stands for jumping off buildings, antennas, spans (such as bridges) and Earth and is illegal in the park.

An investigation concluded that the deaths were accidental. Despite video and photos of the jump, officials consider the specific reason why Potter and Hunt died a mystery.

Richards said she did not know how the rangers reached the bodies but that they worked all day in the "challenging area."

She said officials are investigating when the pair fell and from which part of Taft Point, which is 3,000 feet above the famed Yosemite Valley floor. The victims have not been identified.

The Taft Point overlook has some railings but visitors can walk to the edge of a vertigo-inducing granite ledge that does not have a railing and has become a popular spot for photos posted on social media.

"It's a super-popular place in Yosemite. Really popular for engagements, proposals, weddings," photographer Matt Dippel told CNN. "There were at least three or four different brides and grooms up there doing their post-wedding photos, so it's definitely not an uncommon thing to see up there."

More than 10 people have died at the park this year, six of them from falls and the others from natural causes, park spokesman Scott Gediman said.

Last month, an Israeli teenager fell hundreds of feet to his death while hiking near the top of 600-foot-tall Nevada Fall. The death of 18-year-old Tomer Frankfurter was considered an accident, the Mariposa County coroner's office said.

Taft Point is also where world-famous wingsuit flier Dean Potter and his partner, Graham Hunt, died after leaping from the cliff in 2015. The pair were experienced at flying in wingsuits - the most extreme form of BASE jumping - and crashed after trying to clear a V-shaped notch in a ridgeline.

BASE jumping stands for jumping off buildings, antennas, spans (such as bridges) and Earth and is illegal in the park.

An investigation concluded that the deaths were accidental. Despite video and photos of the jump, officials consider the specific reason why Potter and Hunt died a mystery.

YOSEMITE-WAWONA ELEMENTARY CHARTER SCHOOL

Board of Directors Workshop

Tuesday, October 30, 2018, 5:30 P<

Wawona Elementary School

7925 Chilnualana Falls Road

Wawona, CA

- CALL TO ORDER

- ROLL CALL

MONTHLY ITEMS AND FINANCIAL REPORTS

- HEARING OF PERSONS WISHING TO ADDRESS THE BOARD

ACTION ITEMS

- Discuss and approve Board Member Amber Champion volunteering to assume office responsibilities during time school is closed.

- Discuss and approve of an ad hoc committee to examine funding sources for the school

INFORMATION ITEMS

- Workshop on Board Governance

- ADJOURNMENT

Click here for Board Governance Handbook

US National Weather Service Hanford California

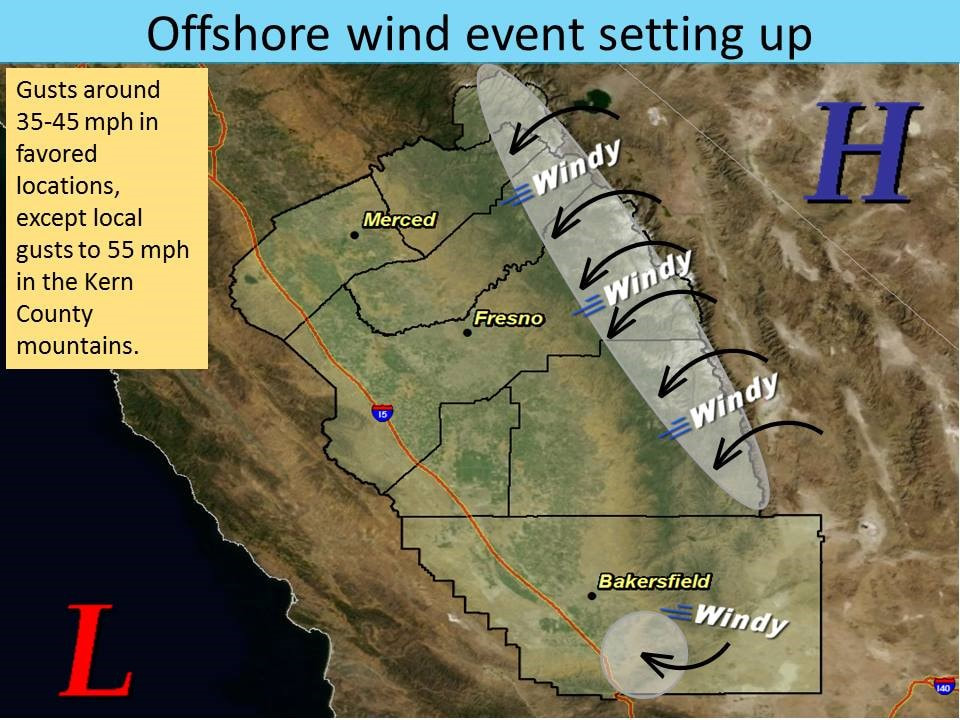

An offshore wind event will likely set up in portions of Central California starting Sunday night. Gusty winds are expected on westward facing slopes in the Sierra Nevada from Sunday night through Monday morning with gusts in favored locations, such as through the canyons, around 35-45 mph. However, locally stronger gusts, or as high as 55 mph, are possible in the Tehachapi Mountains, especially along the slopes facing the southern San Joaquin Valley. Also expect warmer temperatures and low relative humidity during the day on Monday, especially in areas where gusty winds occur. It is also possible trees may fall onto roadways in these areas; drive safe!

For local or point-specific forecasts, please visit weather.gov/hanford and enter in location or zip code.

An offshore wind event will likely set up in portions of Central California starting Sunday night. Gusty winds are expected on westward facing slopes in the Sierra Nevada from Sunday night through Monday morning with gusts in favored locations, such as through the canyons, around 35-45 mph. However, locally stronger gusts, or as high as 55 mph, are possible in the Tehachapi Mountains, especially along the slopes facing the southern San Joaquin Valley. Also expect warmer temperatures and low relative humidity during the day on Monday, especially in areas where gusty winds occur. It is also possible trees may fall onto roadways in these areas; drive safe!

For local or point-specific forecasts, please visit weather.gov/hanford and enter in location or zip code.

Wawona Town Planning Advisory Committee

Regular Meeting

11/16/2018 9:00 AM

Wawona Community Center

7915 Chilnualna Falls Road Wawona, CA 95389

WAWONA TOWN PLANNING ADVISORY COMMITTEE

Tony Christianson 2-28-19

Chuck Jones 2-29-20

Eugene Spindler 2-28-19

Lucy Royse 2-29-20

Edward Mee 2-28-19

Gale Banks 2-29-20

Alton J. Brown 2-29-20

Roger Soulanille 2-29-20

Paul DeSantis 2-29-20

William Rosenberg 2-28-19

Vacant 2-28-19

Vacant 2-28-15

Vacant 2-28-17

Vacant 2-28-18

Forrest Robertson 2-29-20

Ex-Officio Members:

Miles Menetrey Supervisor, District V

John McCamman Planning Commissioner, District V

(Vacant) National Park Service Rep.

Regular Meeting

11/16/2018 9:00 AM

Wawona Community Center

7915 Chilnualna Falls Road Wawona, CA 95389

WAWONA TOWN PLANNING ADVISORY COMMITTEE

Tony Christianson 2-28-19

Chuck Jones 2-29-20

Eugene Spindler 2-28-19

Lucy Royse 2-29-20

Edward Mee 2-28-19

Gale Banks 2-29-20

Alton J. Brown 2-29-20

Roger Soulanille 2-29-20

Paul DeSantis 2-29-20

William Rosenberg 2-28-19

Vacant 2-28-19

Vacant 2-28-15

Vacant 2-28-17

Vacant 2-28-18

Forrest Robertson 2-29-20

Ex-Officio Members:

Miles Menetrey Supervisor, District V

John McCamman Planning Commissioner, District V

(Vacant) National Park Service Rep.

Wawona Area Private Property Owners’ Advocates (WAPPOA) Meeting

Saturday, October 13th, 9:00 AM

Community Center

Please join us for this community meeting

Coffee and Pastries will be served

Saturday, October 13th, 9:00 AM

Community Center

Please join us for this community meeting

Coffee and Pastries will be served