A Year in Yosemite

In May 2009, while hiking in Yosemite National Park, long-time Los Angeles resident Jamie Simons turned to her husband and said, "I want to live here." Months later she and her family made the move to live for one year in Wawona, where her daughter attended the one-room schoolhouse, Jamie wrote, and her husband longed for noise, fast food, people, and the city. (Though he learned to appreciate mountain life.) Eventually they would extend their stay in Yosemite for a third year.

12/08/2009 Year in Yosemite: Into the Park

In May, 2009, while hiking in Yosemite National Park, Jamie Simons and her family stumbled across the public school on the Valley floor. As her daughter made a beeline for the slide, Jamie turned to her husband and said, "I want to live here." Easier said than done if you don't work for the park. But Jamie was persistent and six months later she and her family made the move to live for one year in Wawona, where her daughter attended the one-room schoolhouse. While Jamie wrote, her husband longed for noise, fast food, people, and the sights and sounds of the city.

This was Jamie's first weekly post.

-- Tioga Jenny

I'm standing on top of Sentinel Dome in Yosemite National Park. Below me thunder the waters of Yosemite and Nevada Falls. Directly to my right is Half Dome, to my left, El Capitan and the Three Brothers. My head feels light, whether from the altitude or the view, I can't say. I only know that I feel like the luckiest person alive. For this year, at least, Yosemite is my home.

We moved into the park in mid-August so our daughter could attend one of the park's public schools. She's eight, and as hard as it is for the adult in me to believe that second grade can be grueling, for her it was. It wasn’t that she couldn't keep up (her grades were fine), it's that her natural exuberance and confident nature were being undermined. Now she goes to a one-room schoolhouse with only seven other students. As the only third grader, there is no one with whom to compare herself, nobody who can do third-grade math faster or spell better or read more books. There is no chart up on the classroom door reminding her that everyone is doing better on their timed math tests than she is. With only one teacher, and kids ranging in age from 5 to 10, it’s imperative that she is self-motivated and responsible and she's blossoming under the challenge.

So am I. This summer, once we knew a move to the park was imminent, I kept saying to my L.A. friends (Los Angeles has been our home for over three decades), “I don't know what to expect and that absolutely thrills me.” I loved not knowing what this year would bring. I loved the thought of going somewhere completely different than L.A. I loved not knowing anyone. I loved the idea of having total control of my day. Like my daughter at her new school, the quality of my experience is completely up to me. Now that I'm here, that still thrills me.

Yesterday morning, while talking on the phone, I saw a family of deer run by. My daughter spends hours in the forest that surrounds our home, building forts and stone sculptures. We live in a town so tiny it is the living embodiment of a village raising a child—everyone watches out for each other and for each other's children.

It's not perfect. With winter setting in, you realize that without tasks and hobbies and interests, one could lose one's mind. The nearest groceries are an hour-round-trip on a curvy mountain road. In winter, that same drive, with the added challenges of black ice and snow, can take twice as long. Every once in a while I'll find myself with two or three hours with absolutely nothing to do. Coming from L.A., where it is easy to fill every moment of every day with runs to the store, gabbing or meeting friends, working or running one's kid to endless classes, I find my reaction to the quiet and solitude is panic.

Then the magic of Yosemite takes hold again. I'll go for a walk. Or a hike. Or simply look out the window to see the sun hitting the fall leaves, making them look like a shower of golden coins raining from the trees. On a daily basis, the park surprises and fascinates me: like the Hassidic man standing in Pioneer Village talking on his cell phone or the Germans who stopped to ask me if there is anything worth seeing in Yosemite Valley or the way parents here will drive two hours just to take their kids to school or soccer practice or martial arts. I'm fascinated by the inner workings of the park service and the tourist board and the concessionaire and the homeowners, each with their own agenda and way of perceiving the park. Then there are the visitors, four million of them every year, each with their own experience.

I intend to spend my time in the park getting to know my new home better. Yes, the trails and the hikes and the secret places only the locals know. But I also want to understand just how this place works. Who runs it? How? What does each group bring to the table? I remember years ago (back when Californians actually smoked), picking up a book of matches from Yosemite Lodge. On the front was a picture of Half Dome covered in snow. On the other side were the words “Yosemite. Open all year.” It made me laugh to think that anyone had the chutzpah to think they would or could shut down nature. Of course, Yosemite is open all year—whether any of us are here or not. That is the Yosemite I want to understand as well as the one controlled by man, the one that takes this wild creation of nature and deems it a tourist destination. I hope you'll come along for the walk.

-- Jamie Simons

In May, 2009, while hiking in Yosemite National Park, Jamie Simons and her family stumbled across the public school on the Valley floor. As her daughter made a beeline for the slide, Jamie turned to her husband and said, "I want to live here." Easier said than done if you don't work for the park. But Jamie was persistent and six months later she and her family made the move to live for one year in Wawona, where her daughter attended the one-room schoolhouse. While Jamie wrote, her husband longed for noise, fast food, people, and the sights and sounds of the city.

This was Jamie's first weekly post.

-- Tioga Jenny

I'm standing on top of Sentinel Dome in Yosemite National Park. Below me thunder the waters of Yosemite and Nevada Falls. Directly to my right is Half Dome, to my left, El Capitan and the Three Brothers. My head feels light, whether from the altitude or the view, I can't say. I only know that I feel like the luckiest person alive. For this year, at least, Yosemite is my home.

We moved into the park in mid-August so our daughter could attend one of the park's public schools. She's eight, and as hard as it is for the adult in me to believe that second grade can be grueling, for her it was. It wasn’t that she couldn't keep up (her grades were fine), it's that her natural exuberance and confident nature were being undermined. Now she goes to a one-room schoolhouse with only seven other students. As the only third grader, there is no one with whom to compare herself, nobody who can do third-grade math faster or spell better or read more books. There is no chart up on the classroom door reminding her that everyone is doing better on their timed math tests than she is. With only one teacher, and kids ranging in age from 5 to 10, it’s imperative that she is self-motivated and responsible and she's blossoming under the challenge.

So am I. This summer, once we knew a move to the park was imminent, I kept saying to my L.A. friends (Los Angeles has been our home for over three decades), “I don't know what to expect and that absolutely thrills me.” I loved not knowing what this year would bring. I loved the thought of going somewhere completely different than L.A. I loved not knowing anyone. I loved the idea of having total control of my day. Like my daughter at her new school, the quality of my experience is completely up to me. Now that I'm here, that still thrills me.

Yesterday morning, while talking on the phone, I saw a family of deer run by. My daughter spends hours in the forest that surrounds our home, building forts and stone sculptures. We live in a town so tiny it is the living embodiment of a village raising a child—everyone watches out for each other and for each other's children.

It's not perfect. With winter setting in, you realize that without tasks and hobbies and interests, one could lose one's mind. The nearest groceries are an hour-round-trip on a curvy mountain road. In winter, that same drive, with the added challenges of black ice and snow, can take twice as long. Every once in a while I'll find myself with two or three hours with absolutely nothing to do. Coming from L.A., where it is easy to fill every moment of every day with runs to the store, gabbing or meeting friends, working or running one's kid to endless classes, I find my reaction to the quiet and solitude is panic.

Then the magic of Yosemite takes hold again. I'll go for a walk. Or a hike. Or simply look out the window to see the sun hitting the fall leaves, making them look like a shower of golden coins raining from the trees. On a daily basis, the park surprises and fascinates me: like the Hassidic man standing in Pioneer Village talking on his cell phone or the Germans who stopped to ask me if there is anything worth seeing in Yosemite Valley or the way parents here will drive two hours just to take their kids to school or soccer practice or martial arts. I'm fascinated by the inner workings of the park service and the tourist board and the concessionaire and the homeowners, each with their own agenda and way of perceiving the park. Then there are the visitors, four million of them every year, each with their own experience.

I intend to spend my time in the park getting to know my new home better. Yes, the trails and the hikes and the secret places only the locals know. But I also want to understand just how this place works. Who runs it? How? What does each group bring to the table? I remember years ago (back when Californians actually smoked), picking up a book of matches from Yosemite Lodge. On the front was a picture of Half Dome covered in snow. On the other side were the words “Yosemite. Open all year.” It made me laugh to think that anyone had the chutzpah to think they would or could shut down nature. Of course, Yosemite is open all year—whether any of us are here or not. That is the Yosemite I want to understand as well as the one controlled by man, the one that takes this wild creation of nature and deems it a tourist destination. I hope you'll come along for the walk.

-- Jamie Simons

12/15/2009 Year in Yosemite: Silent Night

When I crawl into bed at night I hear absolutely nothing, or leastways, nothing human. Around my house the air hangs as quiet and still as freshly fallen snow. There's no freeway roar. No garbled noise from a neighbor's TV. No radios. No car engines. Not even conversations. At night, Yosemite is absolutely quiet. For someone like me, who craves silence the way some people crave chocolate, this feels like the ultimate indulgence.

Having a husband who loves the sounds of a city – for him it's a kind of human lullaby –- I understand that there are people who don't love silence the way I do. They love the hustle and bustle. The comings and goings. The sense that life is going on around them at a furious pace. I thought I was one of those people. And, truth be told, for years I was. But during my final two years in Los Angeles, I would wake up every night to the roar of the freeway (which was more than two miles from our home) and know I had to leave the city. The noise was driving me away.

That I ended up somewhere so peaceful is mere happenstance. But as I've quieted down, I've noticed something strange. When people visit from the city they conduct their lives at a louder decibel level than those who live here year round.

This came as a shock. It never occurred to me that city dwellers are so surrounded by noise that they up their sound level just to compete. I'm sure it’s unconscious. But now that I live here, it's startling to me. My findings are less than scientific, just my observations. But it makes me wonder. What did the world sound like before there was man? How noisy were cities 100, 500, 3000 years ago?

When I crawl into bed at night I hear absolutely nothing, or leastways, nothing human. Around my house the air hangs as quiet and still as freshly fallen snow. There's no freeway roar. No garbled noise from a neighbor's TV. No radios. No car engines. Not even conversations. At night, Yosemite is absolutely quiet. For someone like me, who craves silence the way some people crave chocolate, this feels like the ultimate indulgence.

Having a husband who loves the sounds of a city – for him it's a kind of human lullaby –- I understand that there are people who don't love silence the way I do. They love the hustle and bustle. The comings and goings. The sense that life is going on around them at a furious pace. I thought I was one of those people. And, truth be told, for years I was. But during my final two years in Los Angeles, I would wake up every night to the roar of the freeway (which was more than two miles from our home) and know I had to leave the city. The noise was driving me away.

That I ended up somewhere so peaceful is mere happenstance. But as I've quieted down, I've noticed something strange. When people visit from the city they conduct their lives at a louder decibel level than those who live here year round.

This came as a shock. It never occurred to me that city dwellers are so surrounded by noise that they up their sound level just to compete. I'm sure it’s unconscious. But now that I live here, it's startling to me. My findings are less than scientific, just my observations. But it makes me wonder. What did the world sound like before there was man? How noisy were cities 100, 500, 3000 years ago?

As a child I was fascinated with the image of Indians walking through forests, one foot in front of another, so quiet they could track a deer without being heard. Now I wonder if it went beyond their prowess at hunting. As people who lived in nature, did they have an aptitude for quiet?

One of the groups of people on the government payroll in a national park are those in charge of sound control. They monitor the human noise level and, if it gets too loud, remind us to keep it down. They do this as much for the animals as for the visitors. Turns out that one of the ways you protect wildlife is to keep the lid on the sounds produced by humans.

If that's what it takes to keep Yosemite quiet, I say thank you to every deer, bear, mountain lion and fox living in the park. Because of you my nights are filled with silence, broken only by the occasional yipping and howling of a coyote pack on its nighttime rounds, waking me to marvel at its magic and the peacefulness of life away from the freeway's roar.

-- Jamie Simons

The writer's daughter and her friend know exactly what to do when it dumps snow in Yosemite.

The writer's daughter and her friend know exactly what to do when it dumps snow in Yosemite.

12/23/2009 Year in Yosemite: Santa's Baby

Remember the old warning, "If you don't behave, Santa's going to leave a snowball in your stocking?" Turns out at our house that threat rings hollow. There's nothing our daughter would rather get than snow.

Raised in Los Angeles and too young to remember her first and only encounter with the white stuff, she was positively aching to experience it. In October, when the first few flurries showed up, she ran outside, crazy with excitement. But by the time she’d stuck her tongue out to catch the flakes, they had melted in the warming air.

So desperate was she that a November hailstorm sent her flying out onto the deck, where she built teeny little hailmen complete with stone eyes and noses. But then the weather turned unseasonably warm. Most of November was in the 70s.

Remember the old warning, "If you don't behave, Santa's going to leave a snowball in your stocking?" Turns out at our house that threat rings hollow. There's nothing our daughter would rather get than snow.

Raised in Los Angeles and too young to remember her first and only encounter with the white stuff, she was positively aching to experience it. In October, when the first few flurries showed up, she ran outside, crazy with excitement. But by the time she’d stuck her tongue out to catch the flakes, they had melted in the warming air.

So desperate was she that a November hailstorm sent her flying out onto the deck, where she built teeny little hailmen complete with stone eyes and noses. But then the weather turned unseasonably warm. Most of November was in the 70s.

This, of course, made me incredibly happy. In spite of living in a place where snow, ice and cold hang on for 4 or 5 months, I was secretly hoping that this year, winter (perhaps out of sympathy for my thin L.A. blood) would show up for maybe a week or so. In June … while I'm away on vacation.

Promises of global warming aside, at exactly midnight on December 7th, the snow began to fall. It then proceeded to float and flutter to the ground for the next twelve hours. When I first saw it, I thought about waking my daughter. But my ever-practical mother mind (the one that likes to sleep) took over, and I let it go 'til morning.

By then, snow covered everything –- ground, rocks, roads, roofs, trees and cars –- in its winter coat of white. Outside the temperature was a balmy 11 degrees. But that didn't bother my daughter. Normally, she prefers to lie in bed, groaning that she's tired and cold. But on this morning, she jumped out of bed, threw on whatever she could find and made herself breakfast. Then, too excited to eat, she ran out, grabbed the shovel and began to clear off the deck. She might have been trying to get on Santa's good side. She certainly got on mine.

As did the snow. For months I had dreaded its arrival. I don't like to be cold. I certainly have no desire to drive in it. Shoveling? No way. Not for me. But there I was, wrapped up in every outdoor garment I could find, walking my daughter to school in weather that has people across the country making a beeline for the Sun Belt. And I was enjoying every step. In fact, it seemed perfect. Like the way Yosemite is meant to be. Quiet. And white. And beautiful. And serene. Sort of, I imagine, like the North Pole. No wonder Santa lives there.

-- Jamie Simons

Wawona post boxes. Photo by Jon Jay.

Wawona post boxes. Photo by Jon Jay.

12/29/2009 Year in Yosemite: Mail Time

On nice days we often walk to the post office. We leave our house, go past the bear-proof dumpster, through the forest, over a bridge and down Spelt Road (obviously named by natural food fanatics). There we pass the Indian matate sites, get on the trail that runs behind the library and up to the school, cross the road and finish up on the hilly horse trail that takes us directly to Pioneer Village.

At Pioneer Village we walk past the horse stables and a collection of log cabins built in the 1800s, through a covered bridge erected in 1857 and make our way to the parking lot of the Wawona General Store.

To the right of the general store is a stamp-size post office so old there are still bars on the window –- the old-fashioned kind like you see in banks in Westerns –- where you ask for your mail. That is if you don't have a post box.

For the first few months we lived in Yosemite, our mail went to “General Delivery.” Before we moved here I had so little knowledge of rural life that I actually had to ask what “General Delivery” meant. It means this.

No home delivery. No residential address. You just go to the window and ask. My daughter loved this. Xboxes and computer games aside, asking for the mail from a real, live human being gave her an incredible thrill. Sometimes, it's the little things that count.

Then one day I decided it would be nice to have a post box. You have to pay for them but it means you can pick up your mail anytime, 24/7, and not just when the post office is officially open.

If I had realized what a thrill these boxes would give me, I would have rented one sooner. Because they are so charming and old, they remind you more of square dancing than of modern communication. Combinations go something like: circle three times right to A1/2, then left two times to G, pass your partner and it's on to K1/2. Then you do-si-do.

The boxes themselves are so tiny they were surely installed at a time when people wrote on small, wispy pieces of crinkly paper that got tucked into little envelopes and addressed with a perfect hand.

And that hand belonged to a righty. Left-handed myself, it is impossible for me to open my mailbox without my fingers getting in the way, blocking the letters of my weird and wacky combination. No, these boxes belong to a time when teachers prowled the classroom and slapped all lefties' hands with a ruler, forcing them to change to the right.

But it’s worth the finger gymnastics. In these days of instant communication, these boxes are so whimsical and unexpected that one day I know I'll dial in our combination and out will jump Seuss's Thing 1 and Thing 2. I have no doubt they will do-si-do, do an allemande left and then, like us, promenade back home.

-- Jamie Simons

Photo of Half Dome courtesy Tom Valtin.

Photo of Half Dome courtesy Tom Valtin.

01/05/2010 Year in Yosemite: Okay, I Admit It

Somewhere on this planet I know there's a 12-step program designed especially for me. "Hello. My name is Jamie. And I'm addicted to telling people I live in a national park." I can see it all. The dingy room, the folding chairs, the worn linoleum, the bad lighting. Next to me is a woman who calls the Loire Valley home. Across the room is a guy renting a flat in Istanbul. The leader runs a safari park in Kenya. Together we'll join hands and admit we've hit rock bottom. We can’t help ourselves. Wherever we go, we feel compelled to tell people where we live.

And who can blame us? How many times do you get to bask in the glow, not of what you've done, but where you live? I didn’t put Half Dome there or cause Yosemite Falls to thunder down the mountain. Yet I feel special because I inhabit the same piece of real estate they do. It’s the lazy man’s way to ego fulfillment.

Better yet, if done right, it’s subtle, even elegant. No boorish name-dropping (at least not human names). I get all the ooh's and aah's I can handle just from saying "We live in Yosemite. The National Park.

But there's a flip side to loving where you live. Your city friends don't want to hear it. As I wax poetic about the deer wandering by my window, I can sense my friends from home gearing up to stage an intervention.

So I think I've come up with a solution. I'm not going to tell a soul (or at least anyone I'm close to) that I wake up every day and say, "Pinch me, I can't believe I live here." I dwell instead on the bad stuff. Like the curvy mountain roads that become impassable in winter. The isolation. The teeny tiny population of our village. The scarcity of culture. The tension in my marriage because one of us loves the place and the other doesn't. The winter storms. The shoveling. The impossibly long drives just to shop. Moving in and out of our home every few weeks because that's the only way we could find housing. Every bit of it may be true but I don't let people know it's a price I'm willing to pay. Instead, I make it sound bad. Really bad. It's the only way my loved ones will believe I have a handle on my addiction.."

Then, when I can't stand it another moment, when I think I will go crazy, I go to the store and tell the clerk I am buying masses of food because I live in Yosemite National Park and it's a three-hour round trip just to get to Trader Joe's. Instantly I'm rewarded with the ooh's and aah's I crave. My city friends don't even have to know.

But should I slip up and tell them I'm happy, I'll rejoice when they drag me off to the 12-step program for inveterate braggarts. If I play my cards right, I might be able to befriend the woman in the Loire Valley. Surely, she’d like to trade houses for a month. After all, I live in Yosemite National Park.

-- Jamie Simons

Somewhere on this planet I know there's a 12-step program designed especially for me. "Hello. My name is Jamie. And I'm addicted to telling people I live in a national park." I can see it all. The dingy room, the folding chairs, the worn linoleum, the bad lighting. Next to me is a woman who calls the Loire Valley home. Across the room is a guy renting a flat in Istanbul. The leader runs a safari park in Kenya. Together we'll join hands and admit we've hit rock bottom. We can’t help ourselves. Wherever we go, we feel compelled to tell people where we live.

And who can blame us? How many times do you get to bask in the glow, not of what you've done, but where you live? I didn’t put Half Dome there or cause Yosemite Falls to thunder down the mountain. Yet I feel special because I inhabit the same piece of real estate they do. It’s the lazy man’s way to ego fulfillment.

Better yet, if done right, it’s subtle, even elegant. No boorish name-dropping (at least not human names). I get all the ooh's and aah's I can handle just from saying "We live in Yosemite. The National Park.

But there's a flip side to loving where you live. Your city friends don't want to hear it. As I wax poetic about the deer wandering by my window, I can sense my friends from home gearing up to stage an intervention.

So I think I've come up with a solution. I'm not going to tell a soul (or at least anyone I'm close to) that I wake up every day and say, "Pinch me, I can't believe I live here." I dwell instead on the bad stuff. Like the curvy mountain roads that become impassable in winter. The isolation. The teeny tiny population of our village. The scarcity of culture. The tension in my marriage because one of us loves the place and the other doesn't. The winter storms. The shoveling. The impossibly long drives just to shop. Moving in and out of our home every few weeks because that's the only way we could find housing. Every bit of it may be true but I don't let people know it's a price I'm willing to pay. Instead, I make it sound bad. Really bad. It's the only way my loved ones will believe I have a handle on my addiction.."

Then, when I can't stand it another moment, when I think I will go crazy, I go to the store and tell the clerk I am buying masses of food because I live in Yosemite National Park and it's a three-hour round trip just to get to Trader Joe's. Instantly I'm rewarded with the ooh's and aah's I crave. My city friends don't even have to know.

But should I slip up and tell them I'm happy, I'll rejoice when they drag me off to the 12-step program for inveterate braggarts. If I play my cards right, I might be able to befriend the woman in the Loire Valley. Surely, she’d like to trade houses for a month. After all, I live in Yosemite National Park.

-- Jamie Simons

Meadow Loop Trail. Photo courtesy Jon Jay.

Meadow Loop Trail. Photo courtesy Jon Jay.

01/12/2010 Year in Yosemite: Lessons on the Loop Trail

Here's what a day off from school looks like in a national park: No museums. No movies. No fast-food restaurants or visits to Chuck E. Cheese. Instead, you gather every child you know and head out on a trail.

That's when you find out that kids who have been raised in a national park don't necessarily like hiking. When nature is all you know, nature isn't necessarily that appealing. The kid who wants to organize a hiking club and walks for miles with nary a complaint happens to be my own. And she was raised in a city. The other kids make it about half a mile and then ask to turn back or beg to be carried or they stop every two seconds for something to eat.

Which brings me to my next important lesson. Think small. When I organized the day, I was thinking we’d drive out to Sentinel Dome, my favorite Yosemite trail. Sure, it's a long way from where we live but I thought it had all the kid essentials. It’s easy to do with a huge payoff — the views are some of the best in the park. Big news. When you are 4, 6, 8 or 9, as were the kids on our hike, hanging with your friends and throwing leaves at each other is more exciting than staring at Half Dome.

So after that half-mile on the virtually flat (but still quite gorgeous) Meadow Trail, we turned around and headed for home. The plan for the rest of the day? Arts and crafts collages made with leaves we’d found in the forest.

But wait. Not so fast. It was time for my next lesson. You see, the kids on this hike were not just any kids. For the most part, they were the children of park employees. Kids whose parents take the admonition that what you find in the park stays in the park very seriously. In the city, you might organize a hike, pick up leaves, take them home, hand out bottles of glue and glitter and pat yourself on the back for getting your kids outside at all. In a national park, you have a designated leaf picker who brings bags of them from her home outside the park. Who knew?

There are times since moving here when I feel as if I've entered a special realm — a place where Mayberry has collided with Northern Exposure with a hint of Seinfeld thrown in. Life up here is charming and funny and surprising too in ways this city mom could have never guessed. We came here for our daughter's schooling, but her mom is getting the education.

-- Jamie Simons

Here's what a day off from school looks like in a national park: No museums. No movies. No fast-food restaurants or visits to Chuck E. Cheese. Instead, you gather every child you know and head out on a trail.

That's when you find out that kids who have been raised in a national park don't necessarily like hiking. When nature is all you know, nature isn't necessarily that appealing. The kid who wants to organize a hiking club and walks for miles with nary a complaint happens to be my own. And she was raised in a city. The other kids make it about half a mile and then ask to turn back or beg to be carried or they stop every two seconds for something to eat.

Which brings me to my next important lesson. Think small. When I organized the day, I was thinking we’d drive out to Sentinel Dome, my favorite Yosemite trail. Sure, it's a long way from where we live but I thought it had all the kid essentials. It’s easy to do with a huge payoff — the views are some of the best in the park. Big news. When you are 4, 6, 8 or 9, as were the kids on our hike, hanging with your friends and throwing leaves at each other is more exciting than staring at Half Dome.

So after that half-mile on the virtually flat (but still quite gorgeous) Meadow Trail, we turned around and headed for home. The plan for the rest of the day? Arts and crafts collages made with leaves we’d found in the forest.

But wait. Not so fast. It was time for my next lesson. You see, the kids on this hike were not just any kids. For the most part, they were the children of park employees. Kids whose parents take the admonition that what you find in the park stays in the park very seriously. In the city, you might organize a hike, pick up leaves, take them home, hand out bottles of glue and glitter and pat yourself on the back for getting your kids outside at all. In a national park, you have a designated leaf picker who brings bags of them from her home outside the park. Who knew?

There are times since moving here when I feel as if I've entered a special realm — a place where Mayberry has collided with Northern Exposure with a hint of Seinfeld thrown in. Life up here is charming and funny and surprising too in ways this city mom could have never guessed. We came here for our daughter's schooling, but her mom is getting the education.

-- Jamie Simons

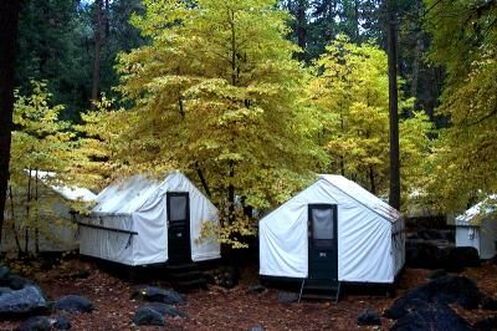

Tent cabins at Camp Curry, Yosemite National Park. Photo courtesy Delaware North Campanies.

Tent cabins at Camp Curry, Yosemite National Park. Photo courtesy Delaware North Campanies.

01/19/2010 Year in Yosemite: The Housing Crisis

If the idea of living inside Yosemite National Park sounds enchanting, I can tell you now that the key to accomplishing this feat can be summed up in one word…housing. The challenge? There isn’t any…or at least any that hasn’t been spoken for.

If you work for the park service, chances are you live outside the park. If you work for the concessionaire but you have children, chances are you live outside the park. If you are a private citizen and don’t own gobs of Berkshire Hathaway stock, chances are you live outside the park.

So what are all those homes I see on the valley floor, you ask? They belong to two groups of people. The first is park service employees who are deemed "required occupants." That means that they are essentially on call 24/7. So if you are a law- enforcement ranger -- the type who patrols the roads, or works in search and rescue, or arrests the drunk and disorderly -- you live inside the park. If you are a firefighter, you live inside the park. If you are the superintendent or the chief ranger, you live inside the park.

If the idea of living inside Yosemite National Park sounds enchanting, I can tell you now that the key to accomplishing this feat can be summed up in one word…housing. The challenge? There isn’t any…or at least any that hasn’t been spoken for.

If you work for the park service, chances are you live outside the park. If you work for the concessionaire but you have children, chances are you live outside the park. If you are a private citizen and don’t own gobs of Berkshire Hathaway stock, chances are you live outside the park.

So what are all those homes I see on the valley floor, you ask? They belong to two groups of people. The first is park service employees who are deemed "required occupants." That means that they are essentially on call 24/7. So if you are a law- enforcement ranger -- the type who patrols the roads, or works in search and rescue, or arrests the drunk and disorderly -- you live inside the park. If you are a firefighter, you live inside the park. If you are the superintendent or the chief ranger, you live inside the park.

But if you are an interpretive ranger, the type of ranger who gives the walks and talks, you live outside the park. If you work in administration, you live outside the park. If you work in forestry, you live outside the park. If you are an archeologist, you live outside the park. If your area of expertise is trail building or sound control or education, you live outside the park. In other words, most park-service employees live outside the park.

The other group living inside the park is the concessionaire’s employees -- not all of them, just those in management and those who are willing to live in dorms (which is what makes it tough to house families).

So how did my husband, daughter, and I manage to live here? For one, we don’t live on the Yosemite Valley floor. We live in a teeny-tiny village where private home-ownership is allowed. But even here, housing is virtually non-existent. We’re only here because once I knew there were public schools in the park, nothing was going to deter me from my mission.

I began searching for a home in Yosemite last May. My goal was to be moved in by the time school started in mid-August. Since I’d just been in the park on a travel-writing assignment, I started with the people who played host during our stay, the concessionaire. In Yosemite’s case it’s a family business (one that’s two billion dollars strong) called Delaware North Companies (DNC). They are the people responsible for filling the beds and the restaurants in Curry Village, Yosemite Lodge at the Falls, The Ahwahnee, and the Wawona Hotel.

They instantly took to the idea of my living in the park with my family and writing about it. For a week, their top guns sought out housing for us. After seven days, the call came through: "The only housing we can locate is a tent cabin in Curry Village. There’s no kitchen, no bathroom, no heat or indoor plumbing, and one of you would have to work for DNC to qualify to get it."

"Um, no thanks." (Believe it or not, many DNC employees are ecstatic to get even this most basic of housing as it means they can live in the valley and avoid a long commute to work.)

Clearly this was not going to be as easy as I’d hoped. After ruling out Foresta and Yosemite West –- too much snow, too tiny, too far from our daughter’s school –- I took the advice of a DNC employee and zeroed in on Wawona.

It’s lovely here –- far from the hustle and bustle of the valley floor, close to the south gate so getting out of the park is not the time-consuming ordeal it is when you live on the valley floor. There’s a school, a library, and a vibrant, welcoming, interesting population. There’s only one problem. And you’ve probably guessed it. There is no housing.

If you want to buy, you have to wrap your mind around the fact that two-bedroom/two-bath cabins go for about a million dollars. People who own homes (which have usually been passed down in families for generations) either use them themselves or rent them for between $400 and $750 a night during high season.

So what’s a girl to do? In our case, we compromised. We knew somebody who knew somebody who knew somebody who agreed to let us use their cabin, but we move out every time they, or their friends, want to use it. And I don’t mean "pack a suitcase and hit the road" moving out. I mean "empty the cupboards, the refrigerator, dressers and closets" moving out.

Is it fun? No. Do we do it so we can be here? Yep. Are we hoping to win the lottery so we can buy that two-bedroom/two-bath? You bet.

Still want to live in a national park? The park superintendent’s job is open and that house is amazing -- comes with everything including a view of Half Dome and indoor plumbing.

-- Jamie Simons

10/27/2010 Year in Yosemite: The Long and Winding Road

When I first became a parent, countless people came forward with advice. Almost all of it was useful and appreciated but none of it had the enduring quality of what my brother calls his First Rule of Parenting—never leave home without a coloring book and a bagel. In other words, if you want happy children, keep them fed and entertained.

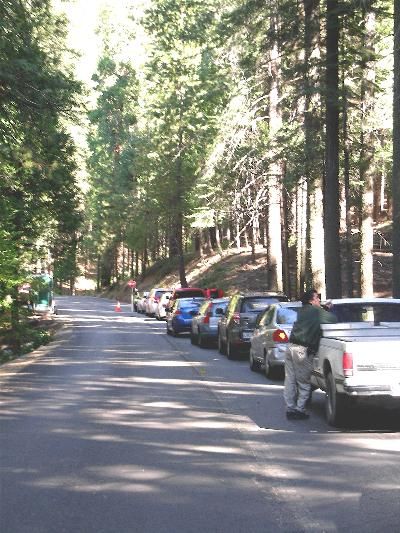

These days I think of this rule every time I drive in Yosemite National Park. Thanks to the nation’s tax dollars, the south end of the park is getting a newly asphalted, spiffed-up road, complete with gutters and freshly painted double lines. What that means for future visitors is smooth roads and easier driving. For now, what that means is weekday traffic delays and congestion, with stops sometimes totaling more than an hour.

It seems to me there are two kinds of fear—the real kind that warns us to fight or take flight and the kind that exists in our head. I excel at the latter. When my family and I moved to the village of Wawona in Yosemite National Park a year ago, we moved to a place that is the very epitome of serenity and quiet. Life—or what most people call life—seems far, far away. I don’t read the newspaper (at least when the news is happening), seldom watch television or listen to the radio. Instead I take walks, watch the wind in the trees that tower over our home, and escort my daughter to her various activities. But tranquility must be more than my mind can stand because I’ve found a way to be white-knuckle Blair Witch afraid. And it’s not from thoughts of anything or anyone jumping out at me from the forest. I’ve put all my fear eggs in one basket, a basket I call The Road.

When I first became a parent, countless people came forward with advice. Almost all of it was useful and appreciated but none of it had the enduring quality of what my brother calls his First Rule of Parenting—never leave home without a coloring book and a bagel. In other words, if you want happy children, keep them fed and entertained.

These days I think of this rule every time I drive in Yosemite National Park. Thanks to the nation’s tax dollars, the south end of the park is getting a newly asphalted, spiffed-up road, complete with gutters and freshly painted double lines. What that means for future visitors is smooth roads and easier driving. For now, what that means is weekday traffic delays and congestion, with stops sometimes totaling more than an hour.

It seems to me there are two kinds of fear—the real kind that warns us to fight or take flight and the kind that exists in our head. I excel at the latter. When my family and I moved to the village of Wawona in Yosemite National Park a year ago, we moved to a place that is the very epitome of serenity and quiet. Life—or what most people call life—seems far, far away. I don’t read the newspaper (at least when the news is happening), seldom watch television or listen to the radio. Instead I take walks, watch the wind in the trees that tower over our home, and escort my daughter to her various activities. But tranquility must be more than my mind can stand because I’ve found a way to be white-knuckle Blair Witch afraid. And it’s not from thoughts of anything or anyone jumping out at me from the forest. I’ve put all my fear eggs in one basket, a basket I call The Road.

Starting in the town of Oakhurst 22 miles south of us, and snaking its way through the park to the Valley floor 26 miles north is a two-lane highway the state calls 41 and I call pure hell. It twists and turns and presents endless blind curves and that’s just on the way going down. Coming back to Wawona from either Oakhurst or the Valley, there are numerous places where one could plummet off the side, if one chose to do so.

-- Jamie Simons

-- Jamie Simons

11/11/2010 Year in Yosemite: It's Official

It’s official. I am now a country girl. I know this because I just spent the last week in Los Angeles. My daughter Karis and I went down there for a few days and had an absolutely fantastic time. Because of Yosemite’s tiny population of year-round residents, my daughter’s friends are few and far between. In Los Angeles, she is wildly popular. For three days she had a play date with a different friend every couple of hours.

Ditto for me. I don’t know if I’m wildly popular but I do count myself lucky to have a large group of extraordinary friends. I had breakfast, lunch and dinner dates and still couldn’t get everyone in. That’s the great blessing of Los Angeles. Having lived there for decades, I’ve had the good fortune to create a family of friends where the bonds of love run true and deep. So why aren’t we hightailing it back to the city?

In a word: the quiet. Los Angeles may have hustle and excitement and great restaurants and gobs of endless entertainment, but it can’t begin to compete with Yosemite when it comes to silence. For whatever reason, my daughter and I can’t seem to get enough of it. We drink it in like ambrosia. It seems to calm our souls.

This is not what I thought would happen when we took up residence here. By nature, I’m social, chatty, and out-going. I never spent a moment in nature (aside from summer camp, which I loathed) until I was 22. I was in love with cities and everything they had to offer from shops to restaurants to museums.

My husband is at the other side of the spectrum. He’s quiet and calm, gracious to everyone but a loner at heart. He spent his childhood playing in the woods and now, surprisingly, he craves the noise and bustle of the city with exactly the same intensity my daughter and I feel for life in the park. This has come as a shock to anyone who knows us. Everyone was convinced that Jon would take to Yosemite like the proverbial fish to water and I would run back to the city within weeks. But the opposite has held true.

So here’s my theory. Contrary to what anyone would expect, I think ADHD people like me do best in a quiet setting. My mind has a tendency to bounce around like a jackrabbit, so there is something about the utter calm of this place that makes me feel alive. At last, the constant chatter in my head is forced to take a breather and I can concentrate—at least more of the time. The same holds true for our daughter. We moved here because by second grade the noise and constant movement in a typical big-city classroom were literally driving her to distraction. She could not focus and we were hearing about it from her teachers on a daily basis.

Still, much as I love it here, I feel a permanent sense of ambivalence. Living with someone who dislikes what you love is not an easy task. My husband and I have what I call a “Gift of the Magi” marriage. He’s forever giving up what he wants to make me happy and I, in turn, try to do the same. That leaves us with two loving people at cross-purposes.

On the final leg of our journey back to Yosemite, Karis started to talk about missing her L.A. friends. With my husband in mind, I said, “You know honey, we can always move back to the city.” “No way!” came the vehement cry from the back seat, “I need the quiet.” That afternoon it was rainy and dark on the drive home along Highway 41. The pine trees looked black in the deepening gloom. In and around them were luminous golden and red-leaved oaks and aspens, making the forest seem lit from within. Shocked once again by the startling beauty of this place, all I could say was, “So do I, baby. So do I.”

-- Jamie Simons

It’s official. I am now a country girl. I know this because I just spent the last week in Los Angeles. My daughter Karis and I went down there for a few days and had an absolutely fantastic time. Because of Yosemite’s tiny population of year-round residents, my daughter’s friends are few and far between. In Los Angeles, she is wildly popular. For three days she had a play date with a different friend every couple of hours.

Ditto for me. I don’t know if I’m wildly popular but I do count myself lucky to have a large group of extraordinary friends. I had breakfast, lunch and dinner dates and still couldn’t get everyone in. That’s the great blessing of Los Angeles. Having lived there for decades, I’ve had the good fortune to create a family of friends where the bonds of love run true and deep. So why aren’t we hightailing it back to the city?

In a word: the quiet. Los Angeles may have hustle and excitement and great restaurants and gobs of endless entertainment, but it can’t begin to compete with Yosemite when it comes to silence. For whatever reason, my daughter and I can’t seem to get enough of it. We drink it in like ambrosia. It seems to calm our souls.

This is not what I thought would happen when we took up residence here. By nature, I’m social, chatty, and out-going. I never spent a moment in nature (aside from summer camp, which I loathed) until I was 22. I was in love with cities and everything they had to offer from shops to restaurants to museums.

My husband is at the other side of the spectrum. He’s quiet and calm, gracious to everyone but a loner at heart. He spent his childhood playing in the woods and now, surprisingly, he craves the noise and bustle of the city with exactly the same intensity my daughter and I feel for life in the park. This has come as a shock to anyone who knows us. Everyone was convinced that Jon would take to Yosemite like the proverbial fish to water and I would run back to the city within weeks. But the opposite has held true.

So here’s my theory. Contrary to what anyone would expect, I think ADHD people like me do best in a quiet setting. My mind has a tendency to bounce around like a jackrabbit, so there is something about the utter calm of this place that makes me feel alive. At last, the constant chatter in my head is forced to take a breather and I can concentrate—at least more of the time. The same holds true for our daughter. We moved here because by second grade the noise and constant movement in a typical big-city classroom were literally driving her to distraction. She could not focus and we were hearing about it from her teachers on a daily basis.

Still, much as I love it here, I feel a permanent sense of ambivalence. Living with someone who dislikes what you love is not an easy task. My husband and I have what I call a “Gift of the Magi” marriage. He’s forever giving up what he wants to make me happy and I, in turn, try to do the same. That leaves us with two loving people at cross-purposes.

On the final leg of our journey back to Yosemite, Karis started to talk about missing her L.A. friends. With my husband in mind, I said, “You know honey, we can always move back to the city.” “No way!” came the vehement cry from the back seat, “I need the quiet.” That afternoon it was rainy and dark on the drive home along Highway 41. The pine trees looked black in the deepening gloom. In and around them were luminous golden and red-leaved oaks and aspens, making the forest seem lit from within. Shocked once again by the startling beauty of this place, all I could say was, “So do I, baby. So do I.”

-- Jamie Simons

11/24/2010 Year in Yosemite: Moving On

I'm a person who looks for signs everywhere. Not the "Eat Here" or "Gas Ahead" type, but little messages from the universe that I interpret to mean I am, or am not, on the right path. I know I'm being foolish, but like the fortune that comes at the end of a Chinese meal, I tuck away the ones I feel lend hope or meaning to my life and discard the rest. Lately, I’m questioning this practice. Because all the signs regarding our move to Yosemite National Park seem to be weighing in on the negative side and I've begun to wonder why we're here.

A year ago, I felt like I could easily have been cast in a Boeing commercial. At the time, their "We know why we're here" slogan was my daily mantra. We had moved to Yosemite for our daughter Karis and to feed my hunger for adventure. Tired of the noise and distractions of Los Angeles, both Karis and I needed time to regroup and quiet down — she in the classroom, me in life. We found that here. Amid the quiet and the beauty, I felt at peace.

Staying far away from the madness of Yosemite Valley, we settled in Wawona, a tiny hamlet at the southern end of the park where the year-round population hovers around 150. Our daughter started at the one-room schoolhouse and my husband and I tried to make a home . . . but that was not to be. We were so desperate to get up here and enroll our daughter in the local school, that I made a fatal calculation. I agreed to move into a house from which we had to move every time the owners wanted to use it themselves and/or whenever they could get more money from someone else — a "deal" which produced the odd sensation of feeling homeless while paying a rather sizable rent.

Now in the middle of our 17th move in 14 months, I realize how deeply this constant feeling of instability has colored our time in the park. I'm not calm. I'm not relaxed. And I'm looking everywhere for signs that it's time to leave. Nature complied by dropping 28 inches of snow the day before our latest move, then sending temperatures plummeting to Arctic lows. Our daughter's school complied by becoming, once again, immersed in the seemingly endless drama to keep its doors open. Our daughter even seemed to comply. Her lack of focus in the classroom was our main motivator for making this move, so my heart grew heavy as her teachers complained about her inability to stay "on task" (this in a classroom with nine children and three adults). Listening to them, something inside me broke and all I could think about was leaving.

Then, in the midst of it all, there appeared signs that maybe we belong here after all. On a Saturday morning, a friend offered to help us move our wood. Our soon-to-be new neighbor called to lend us his truck. One of the women I hike with declared a moving/cleaning/painting day at our new home in lieu of our usual rovings. Another friend emailed to invite us to live with them while we vacated one house and waited for the next one to be ready. Our beloved across-the-street neighbors (who were the very best part of where we have been living) let us store our things and took our daughter at a moment's notice whenever we needed to pack. Every time we walked down the street, people stopped to ask if we needed help. Even the librarian offered her assistance.

On a day when the snow was constant and my mood at its lowest, the Seventh Day Adventist Camp staff (we are not Seventh Day Adventist ourselves, but they have been extraordinarily kind neighbors) called to say they wanted to help us paint and fix up the house we’re moving to (a lovely place but in much need of TLC). When I asked what it would cost, they answered, "It's our Christmas gift. If you insist, you can make a donation to a worthy cause."

I'm a person who looks for signs everywhere. Not the "Eat Here" or "Gas Ahead" type, but little messages from the universe that I interpret to mean I am, or am not, on the right path. I know I'm being foolish, but like the fortune that comes at the end of a Chinese meal, I tuck away the ones I feel lend hope or meaning to my life and discard the rest. Lately, I’m questioning this practice. Because all the signs regarding our move to Yosemite National Park seem to be weighing in on the negative side and I've begun to wonder why we're here.

A year ago, I felt like I could easily have been cast in a Boeing commercial. At the time, their "We know why we're here" slogan was my daily mantra. We had moved to Yosemite for our daughter Karis and to feed my hunger for adventure. Tired of the noise and distractions of Los Angeles, both Karis and I needed time to regroup and quiet down — she in the classroom, me in life. We found that here. Amid the quiet and the beauty, I felt at peace.

Staying far away from the madness of Yosemite Valley, we settled in Wawona, a tiny hamlet at the southern end of the park where the year-round population hovers around 150. Our daughter started at the one-room schoolhouse and my husband and I tried to make a home . . . but that was not to be. We were so desperate to get up here and enroll our daughter in the local school, that I made a fatal calculation. I agreed to move into a house from which we had to move every time the owners wanted to use it themselves and/or whenever they could get more money from someone else — a "deal" which produced the odd sensation of feeling homeless while paying a rather sizable rent.

Now in the middle of our 17th move in 14 months, I realize how deeply this constant feeling of instability has colored our time in the park. I'm not calm. I'm not relaxed. And I'm looking everywhere for signs that it's time to leave. Nature complied by dropping 28 inches of snow the day before our latest move, then sending temperatures plummeting to Arctic lows. Our daughter's school complied by becoming, once again, immersed in the seemingly endless drama to keep its doors open. Our daughter even seemed to comply. Her lack of focus in the classroom was our main motivator for making this move, so my heart grew heavy as her teachers complained about her inability to stay "on task" (this in a classroom with nine children and three adults). Listening to them, something inside me broke and all I could think about was leaving.

Then, in the midst of it all, there appeared signs that maybe we belong here after all. On a Saturday morning, a friend offered to help us move our wood. Our soon-to-be new neighbor called to lend us his truck. One of the women I hike with declared a moving/cleaning/painting day at our new home in lieu of our usual rovings. Another friend emailed to invite us to live with them while we vacated one house and waited for the next one to be ready. Our beloved across-the-street neighbors (who were the very best part of where we have been living) let us store our things and took our daughter at a moment's notice whenever we needed to pack. Every time we walked down the street, people stopped to ask if we needed help. Even the librarian offered her assistance.

On a day when the snow was constant and my mood at its lowest, the Seventh Day Adventist Camp staff (we are not Seventh Day Adventist ourselves, but they have been extraordinarily kind neighbors) called to say they wanted to help us paint and fix up the house we’re moving to (a lovely place but in much need of TLC). When I asked what it would cost, they answered, "It's our Christmas gift. If you insist, you can make a donation to a worthy cause."

That's Wawona. That's our home. In a place where being kind is a necessity, not an indulgence, once again community trumped all—my fear, my feelings of wanting to run, my deep dislike of snow, ice, and cold. (The next time I want an adventure, I'm opting for some place warm).

Every day last year a family of deer grazed outside our bedroom window. I came to think of them as neighbors, too, and was cheered by their daily appearance. This year they didn't come, even once. Then, on our final day in our move-in/move-out house, there they were, led this time by the most magnificent buck I’ve ever seen. As I stood transfixed, he raised his head and stared directly at me. Was this a sign that we belong here? Or a last farewell before we move on?

-- Jamie Simons

Every day last year a family of deer grazed outside our bedroom window. I came to think of them as neighbors, too, and was cheered by their daily appearance. This year they didn't come, even once. Then, on our final day in our move-in/move-out house, there they were, led this time by the most magnificent buck I’ve ever seen. As I stood transfixed, he raised his head and stared directly at me. Was this a sign that we belong here? Or a last farewell before we move on?

-- Jamie Simons

12/09/2010 Year In Yosemite: Time to Celebrate?

My family has lived in Yosemite National Park for a grand total of 16 months. Oddly enough for such a short sojourn, some things already loom large in my mind as established tradition. One of these is the divvying up of holidays among the tiny populace of Wawona, where we live. One family hosts Halloween, another Cinco de Mayo, and still another New Year’s Eve. Because my daughter is originally from China, I called dibs on Chinese New Year, and in homage to my own background, Hanukah . . . at least last year I did.

This year is different. We’re moving . . . again. And with our new home stacked up with boxes and bins, there was no chance to find our menorah and no time to drive to Fresno to buy the ritual foods. So Hanukah, at least the community celebration of it, was a no go for us.For a while I was bummed. Along with my sanity, it seemed like one more casualty of our near constant moves. Then, amazingly enough for someone secular like myself; I began to reflect on the meaning of the holiday. From a historical/religious point of view, Hanukah marks the defeat of a large, established army by the Maccabees, a tiny group of warriors. Once they won, they purified the Second Temple and, to mark the occasion, lit the eight-branched menorah. The only problem? They had enough oil to burn for 24 hours; they needed enough to burn for eight days. In what many consider a miracle, that tiny bit of oil burned for the whole week, hence Hanukah, the eight-day Celebration of Lights.

But that’s the historical, not the spiritual side of Hanukah, which rabbis explain something like this: The tiny army taking on a larger foe teaches that when we think we’re not enough, we are, while the lighting of the oil shows us that when we think there isn’t enough, there is. The rededication of the temple means the impure can be made pure again and the miracle of the oil is not that it lasted for eight days but that, knowing there wasn’t enough, someone had the faith to light it anyway.

My family has lived in Yosemite National Park for a grand total of 16 months. Oddly enough for such a short sojourn, some things already loom large in my mind as established tradition. One of these is the divvying up of holidays among the tiny populace of Wawona, where we live. One family hosts Halloween, another Cinco de Mayo, and still another New Year’s Eve. Because my daughter is originally from China, I called dibs on Chinese New Year, and in homage to my own background, Hanukah . . . at least last year I did.

This year is different. We’re moving . . . again. And with our new home stacked up with boxes and bins, there was no chance to find our menorah and no time to drive to Fresno to buy the ritual foods. So Hanukah, at least the community celebration of it, was a no go for us.For a while I was bummed. Along with my sanity, it seemed like one more casualty of our near constant moves. Then, amazingly enough for someone secular like myself; I began to reflect on the meaning of the holiday. From a historical/religious point of view, Hanukah marks the defeat of a large, established army by the Maccabees, a tiny group of warriors. Once they won, they purified the Second Temple and, to mark the occasion, lit the eight-branched menorah. The only problem? They had enough oil to burn for 24 hours; they needed enough to burn for eight days. In what many consider a miracle, that tiny bit of oil burned for the whole week, hence Hanukah, the eight-day Celebration of Lights.

But that’s the historical, not the spiritual side of Hanukah, which rabbis explain something like this: The tiny army taking on a larger foe teaches that when we think we’re not enough, we are, while the lighting of the oil shows us that when we think there isn’t enough, there is. The rededication of the temple means the impure can be made pure again and the miracle of the oil is not that it lasted for eight days but that, knowing there wasn’t enough, someone had the faith to light it anyway.

All of which adds up to a Hanukah that this year had real meaning for me. With Yosemite’s none-too-inviting winter weather, all the moves and, quite frankly, the inconvenience of living in such a rural place, this last year has been hard for my husband and myself—but it’s been a blessing for our daughter. In the midst of our biggest move yet, I began to wonder if adult needs should trump our daughter’s.

But as person after person—from friends to neighbors to the entire staff of the local Seventh Day Adventist Camp—came forward to offer their help with cleaning and packing and painting, I realized my life had become the living embodiment of Hanukah. When I felt I didn’t have enough left inside to make this move, my neighbors proved that, with their help, I was stronger than I knew. Together they formed an army of goodness that pushed away the darkness—or, in our case, the cobwebs. And so, here we’ll stay, and sometime around mid-January, when I finally find that menorah tucked away in its box, we’ll pull it out. Then we’ll invite the friends who’ve helped make our new home a cause for celebration and have a rousing party that speaks to our own kind of miracle—living each day in the Range of Light.

-- Jamie Simons

But as person after person—from friends to neighbors to the entire staff of the local Seventh Day Adventist Camp—came forward to offer their help with cleaning and packing and painting, I realized my life had become the living embodiment of Hanukah. When I felt I didn’t have enough left inside to make this move, my neighbors proved that, with their help, I was stronger than I knew. Together they formed an army of goodness that pushed away the darkness—or, in our case, the cobwebs. And so, here we’ll stay, and sometime around mid-January, when I finally find that menorah tucked away in its box, we’ll pull it out. Then we’ll invite the friends who’ve helped make our new home a cause for celebration and have a rousing party that speaks to our own kind of miracle—living each day in the Range of Light.

-- Jamie Simons

Photo by Karis Simons

Photo by Karis Simons

01/13/2011 Year in Yosemite: Perfection

Can a day be perfect? When people hear that my family and I live in Yosemite National Park, they seem to assume that each day is awash with wonder and contentment. And while it’s true that I only have to walk outside on a sunny day to feel happy and alive, those times are tempered by real life—a husband who loves Yosemite’s beauty but finds it too isolated and too quiet, a child who seems allergic to homework and a home still in need of unpacking and organizing one month after we moved in.

So can a day in Yosemite be perfect? Based on a Christmas visit to Yosemite Valley, when the whole, exquisite dreamscape that makes up the heart of the park seemed like it was putting on a holiday show, even my “I’d rather be in L.A.” husband would answer with a hearty yes.

Part of its magic was probably due to the fact that the day was completely unplanned. My niece and her best friend Kathy had come to Wawona to help us unpack a seemingly endless stack of boxes and bins. Knowing this was to be a work trip, they hoped to squeeze in a couple of quick hikes around our house. Desperate to make use of their strong backs and organizational skills, I was one with that plan.

Can a day be perfect? When people hear that my family and I live in Yosemite National Park, they seem to assume that each day is awash with wonder and contentment. And while it’s true that I only have to walk outside on a sunny day to feel happy and alive, those times are tempered by real life—a husband who loves Yosemite’s beauty but finds it too isolated and too quiet, a child who seems allergic to homework and a home still in need of unpacking and organizing one month after we moved in.

So can a day in Yosemite be perfect? Based on a Christmas visit to Yosemite Valley, when the whole, exquisite dreamscape that makes up the heart of the park seemed like it was putting on a holiday show, even my “I’d rather be in L.A.” husband would answer with a hearty yes.

Part of its magic was probably due to the fact that the day was completely unplanned. My niece and her best friend Kathy had come to Wawona to help us unpack a seemingly endless stack of boxes and bins. Knowing this was to be a work trip, they hoped to squeeze in a couple of quick hikes around our house. Desperate to make use of their strong backs and organizational skills, I was one with that plan.

Photo by Karis Simons

Photo by Karis Simons

But on their third day here, nature set me straight. After weeks of freezing, snowy weather, the day dawned bright and sunny with temperatures expected in the 60s. That, plus the fact that the two were raised in Ireland and Kathy had never been to Yosemite, made my husband and I decide that a trip to the Valley was in order. I quickly called The Ahwanhee Hotel to make a breakfast reservation only to be told that by the time we made the hour-long trip from Wawona, the dining room would be closed.

Then the lovely woman on the other end of the phone suggested that she tell the dining room we’d be late and see if they’d hold the reservation. We jumped in the car but in spite of our best efforts, a complete lack of traffic, and heroic driving on my husband’s part, we couldn’t make it on time. At 10:30, the very time the dining room closes, my cell phone rang. “Have you made it to the Valley floor yet?” asked the Delaware North employee. “We’re pulling up to the Ahwanhee now,” I replied. “Great,” she said, “because we’re keeping the dining room open for you.”

Needless to say, we couldn’t believe our luck. We bolted from the car and ran for the dining room just to be sure our luck held. It did. But as beautiful as the dining room and the Ahwanhee are, they paled in comparison to what awaited us outside.

In the weeks before our visit, an early winter storm had dumped three feet of snow on the Valley, turning everything white and encasing the autumn leaves in ice. Now with the spring-like temperatures, a fog was rising up from the ground while the sun, blazing down on the golden leaves, made them sparkle like diamonds. Could it get more perfect? Apparently so.

Photo by Jon Jay

Photo by Jon Jay

As we stood in front of the walkway to Yosemite Falls, three enormous bucks came romping through the snow-covered meadow, each displaying a rack of antlers so large and glorious they looked like their names should be Cupid, Donner, and Blitzen. We’ve lived in Yosemite for over a year now and we’ve seen a lot of deer, but until this day I had never seen such huge bucks, one after another, running across a snow-covered field like something straight out of a Christmas card. Then they crossed the road, gathered up their does and fawns and lay down among the visitors allowing people to get close enough to pet them (which thankfully no one did). It was at this point that I began to think the day had taken on an almost mystical aura, something even beyond the normal awe-inspiring beauty of the place.

The feeling was confirmed as we rounded the corner just below El Capitan. Shadows filled the meadow that runs alongside the river. Fog rose. Leaves shimmered. It was a landscape unlike anything I’d witnessed before in the park. Every car stopped. People leapt out with their cameras. My 9-year-old daughter nailed it.

John Muir once wrote, “So abundant and novel are the objects of interest in a pure wilderness that unless you are pursuing special studies it matters little where you go, or how often to the same place. Wherever you chance to be always seems at the moment of all places the best; and you feel that there can be no happiness in this world or in any other for those who may not be happy here.” On that day and in that place, even my husband had to concur.

-- Jamie Simons

As we stood in front of the walkway to Yosemite Falls, three enormous bucks came romping through the snow-covered meadow, each displaying a rack of antlers so large and glorious they looked like their names should be Cupid, Donner, and Blitzen. We’ve lived in Yosemite for over a year now and we’ve seen a lot of deer, but until this day I had never seen such huge bucks, one after another, running across a snow-covered field like something straight out of a Christmas card. Then they crossed the road, gathered up their does and fawns and lay down among the visitors allowing people to get close enough to pet them (which thankfully no one did). It was at this point that I began to think the day had taken on an almost mystical aura, something even beyond the normal awe-inspiring beauty of the place.

The feeling was confirmed as we rounded the corner just below El Capitan. Shadows filled the meadow that runs alongside the river. Fog rose. Leaves shimmered. It was a landscape unlike anything I’d witnessed before in the park. Every car stopped. People leapt out with their cameras. My 9-year-old daughter nailed it.

John Muir once wrote, “So abundant and novel are the objects of interest in a pure wilderness that unless you are pursuing special studies it matters little where you go, or how often to the same place. Wherever you chance to be always seems at the moment of all places the best; and you feel that there can be no happiness in this world or in any other for those who may not be happy here.” On that day and in that place, even my husband had to concur.

-- Jamie Simons

Photo by Jon Jay

Photo by Jon Jay

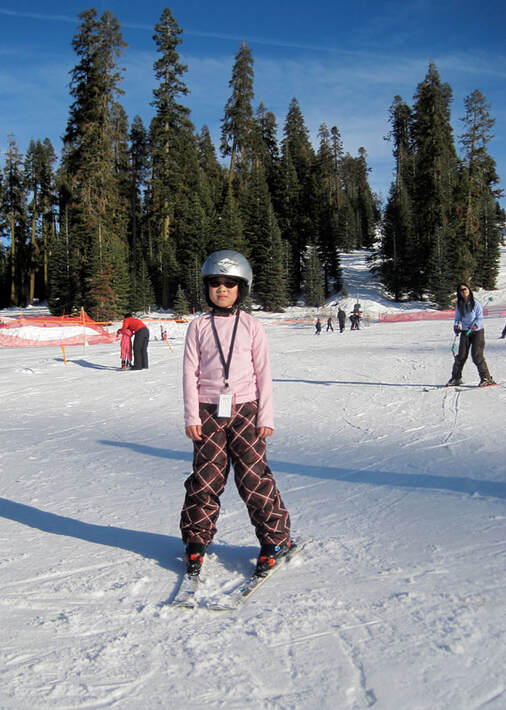

01/22/ Year In Yosemite Yosemite Education: Karis learns to ski.

At 17 months our daughter Karis was diagnosed with a condition that occupational therapists call Sensory Integration Dysfunction. My Jewish mother calls it spilkes (ants in the pants), my friends politely call it busy (usually while shaking their heads in dismay) and most doctors call it hogwash.

Be that as it may, when our daughter was a toddler, she would wash her body in ice cream just for the sensation. She banged her head against the wall without stopping for minutes at a time and shook her head back and forth so violently we thought we were living with Linda Blair in "The Exorcist." She had trouble navigating different surfaces without falling down and when it was time to talk, she could understand everything that was said to her but couldn’t form even a two-word sentence.

Thanks to an enlightened pediatrician, she began therapies to correct these problems when she was 18 months old and by kindergarten she seemed like any other kid...sort of. There was still the little problem of sitting still and paying attention but her personality is so sunny and ebullient, most teachers overlooked this—until second grade.

As I write this, I still have trouble believing that we upended our lives because of second grade problems. But we had done everything we could to even the playing field for her. After horrible experiences with her local public school, we put her in a private school where class sizes were small, kindness was the order of the day and the teachers were enthusiastic and involved. It worked great until she got a teacher who was absolutely fantastic—as long as her students remained seated.

This teacher did everything she could to get Karis to pay attention. But toward the end of the year, I was getting daily calls where she would put Karis on the phone and somehow, magically, I was supposed to get her to perform. Short of stapling her to the chair, I didn’t have any answers. I just had a permanent stomachache and the absolute knowledge that I could not go through another year like that one, and our daughter did not deserve to.

Then, while on a family trip to Yosemite National Park, I brought along Richard Louv’s book Last Child in the Woods and read these words: “The back page of an October issue of San Francisco magazine displays a vivid photograph of a small boy, eyes wide with excitement and joy, leaping and running on a great expanse of California beach, storm clouds and towering waves behind him. A short article explains that the boy was hyperactive, he had been kicked out of his school, and his parents had not known what to do with him, but they had observed how nature engaged and soothed him. So for years they took the son to beaches, forests, dunes, and rivers to let nature do its work.” The photograph was taken in 1907. The boy was Ansel Adams.

Was this a sign? Maybe, because on the same day that I read about Ansel Adams, we got lost on a trail and ended up in front of a school. A school? In a national park? Yes. A public school. Free. No tuition. In heaven’s playground. You could even see Half Dome from the slide. I turned to my husband and said, “Let’s move here.” But it was not to be. The school in the Valley is reserved for kids whose parents live in the park, either because they work for the park service or the concessionaire. It is a public school, so if you are willing to make a treacherous ride over mountain passes in winter conditions, your child can also attend. Much as I love my daughter and want the best for her, one year in I still can’t face the roads in the park, especially in winter, making that school a definite no go.

Then someone mentioned Wawona to us. Sweet, wonderful Wawona. To most people there is absolutely nothing here; it feels like the back of beyond, which I suppose it is. But it boasts a wonderful library and a school. And it was the school that drew us like a magnet because, whether by luck or by chance, it also attracts teachers of unimaginable creativity and talent—people who are able to juggle the needs of kindergartners just learning their letters with sixth graders doing higher math.

More importantly for our daughter, learning takes place all around the classroom, which means she gets to move and that increases her ability to learn. Add in skiing one day a week in winter, outings with naturalists, lunches with rangers, cooking lessons to teach geography, a classroom of kids who think of each other as extended family and you have a prescription for success—not a single child left behind.

At 17 months our daughter Karis was diagnosed with a condition that occupational therapists call Sensory Integration Dysfunction. My Jewish mother calls it spilkes (ants in the pants), my friends politely call it busy (usually while shaking their heads in dismay) and most doctors call it hogwash.

Be that as it may, when our daughter was a toddler, she would wash her body in ice cream just for the sensation. She banged her head against the wall without stopping for minutes at a time and shook her head back and forth so violently we thought we were living with Linda Blair in "The Exorcist." She had trouble navigating different surfaces without falling down and when it was time to talk, she could understand everything that was said to her but couldn’t form even a two-word sentence.

Thanks to an enlightened pediatrician, she began therapies to correct these problems when she was 18 months old and by kindergarten she seemed like any other kid...sort of. There was still the little problem of sitting still and paying attention but her personality is so sunny and ebullient, most teachers overlooked this—until second grade.

As I write this, I still have trouble believing that we upended our lives because of second grade problems. But we had done everything we could to even the playing field for her. After horrible experiences with her local public school, we put her in a private school where class sizes were small, kindness was the order of the day and the teachers were enthusiastic and involved. It worked great until she got a teacher who was absolutely fantastic—as long as her students remained seated.

This teacher did everything she could to get Karis to pay attention. But toward the end of the year, I was getting daily calls where she would put Karis on the phone and somehow, magically, I was supposed to get her to perform. Short of stapling her to the chair, I didn’t have any answers. I just had a permanent stomachache and the absolute knowledge that I could not go through another year like that one, and our daughter did not deserve to.

Then, while on a family trip to Yosemite National Park, I brought along Richard Louv’s book Last Child in the Woods and read these words: “The back page of an October issue of San Francisco magazine displays a vivid photograph of a small boy, eyes wide with excitement and joy, leaping and running on a great expanse of California beach, storm clouds and towering waves behind him. A short article explains that the boy was hyperactive, he had been kicked out of his school, and his parents had not known what to do with him, but they had observed how nature engaged and soothed him. So for years they took the son to beaches, forests, dunes, and rivers to let nature do its work.” The photograph was taken in 1907. The boy was Ansel Adams.