Photo credit: Chad Andrews

Photo credit: Chad Andrews

05/09/2011 Year in Yosemite: Animal Kingdom

Rumor has it that there are 230 species of birds and 80 species of mammals in Yosemite National Park. After living here for 18-plus months, I'd like to ask, "Exactly where?" Because while it's true that on any given day, I might see mule deer, gray squirrels, and an occasional coyote, everything else seems to have headed for the hills — or at least that's the theory. Naturalists working in the park claim that in a space the size of Rhode Island, the animals can't be bothered hanging out around people. According to them, except for black bears looking for easy pickings, most of the animals live in remote areas where there's little chance of human interaction. To which I say, "Hogwash." In the past 18 months, I've seen plenty of wildlife. It's just that none of it has been inside the park.

Ask me where you should go for the best animal viewing and I'd send you off to hang out on Highway 41. Going into Fresno about once a week, I've become fairly obsessed with the red-tailed hawks that seem to sit on every lamppost heading out of town. The farmland may be disappearing but their presence — with their nests stuck onto telephone poles just yards from the road — seems to say, this is still our country.

Same for the golden eagles. The first one I saw was a fledgling hiding in the grass not ten feet from my car. The first one my husband saw was on his way down to Oakhurst from the park. As most readers know, Yosemite is not my husband's favorite place. That he's here is a testament to his devotion to his daughter and our love for her park school. But one day, when his feelings of isolation were at their height, a golden eagle flew along with him as he made his way down the hill, holding itself at window height for about 100 yards. I, at least, took this as a cosmic sign that we were in the right place.

Rumor has it that there are 230 species of birds and 80 species of mammals in Yosemite National Park. After living here for 18-plus months, I'd like to ask, "Exactly where?" Because while it's true that on any given day, I might see mule deer, gray squirrels, and an occasional coyote, everything else seems to have headed for the hills — or at least that's the theory. Naturalists working in the park claim that in a space the size of Rhode Island, the animals can't be bothered hanging out around people. According to them, except for black bears looking for easy pickings, most of the animals live in remote areas where there's little chance of human interaction. To which I say, "Hogwash." In the past 18 months, I've seen plenty of wildlife. It's just that none of it has been inside the park.

Ask me where you should go for the best animal viewing and I'd send you off to hang out on Highway 41. Going into Fresno about once a week, I've become fairly obsessed with the red-tailed hawks that seem to sit on every lamppost heading out of town. The farmland may be disappearing but their presence — with their nests stuck onto telephone poles just yards from the road — seems to say, this is still our country.

Same for the golden eagles. The first one I saw was a fledgling hiding in the grass not ten feet from my car. The first one my husband saw was on his way down to Oakhurst from the park. As most readers know, Yosemite is not my husband's favorite place. That he's here is a testament to his devotion to his daughter and our love for her park school. But one day, when his feelings of isolation were at their height, a golden eagle flew along with him as he made his way down the hill, holding itself at window height for about 100 yards. I, at least, took this as a cosmic sign that we were in the right place.

Photo credit: Charles Phillips

Photo credit: Charles Phillips

On that same road we've seen beaver, deer, and bobcats. Then a few weeks ago, right outside of Oakhurst, I hit the animal jackpot. A huge, enormous bear ran across the road directly in front of my car. I was far enough away to miss it, but close enough to gasp with delight and grab the arm of my passenger while yelling, "A bear. A bear. My first bear."

Now I know there are bears in Yosemite. I know this because when you travel the roads of the park, there are yellow signs painted with red bears and the message "Speed kills." I doubt many visitors to Yosemite know these signs mark the place where a bear was taken out by a car. The signs appear fairly frequently along the roadside, so while I haven't actually seen a bear in the park, I know they are here, along with mountain lions, which many of my neighbors have seen right in my neighborhood. So far, no viewings for me. I'm hoping to keep it that way (unless I'm in the safety of a car).

When Galen Clark became the first guardian of Yosemite in the 1860s, he wrote extensively about the abundance of game — beavers, raccoons, opossum, deer, bear, fox, coyote, mountain lions, and big horn sheep. I've seen several of these species in the backyard of my home in Los Angeles, but never here. To see them in the Sierras, take my advice: stake out a viewing spot along Highway 41.

-- Jamie Simons

Now I know there are bears in Yosemite. I know this because when you travel the roads of the park, there are yellow signs painted with red bears and the message "Speed kills." I doubt many visitors to Yosemite know these signs mark the place where a bear was taken out by a car. The signs appear fairly frequently along the roadside, so while I haven't actually seen a bear in the park, I know they are here, along with mountain lions, which many of my neighbors have seen right in my neighborhood. So far, no viewings for me. I'm hoping to keep it that way (unless I'm in the safety of a car).

When Galen Clark became the first guardian of Yosemite in the 1860s, he wrote extensively about the abundance of game — beavers, raccoons, opossum, deer, bear, fox, coyote, mountain lions, and big horn sheep. I've seen several of these species in the backyard of my home in Los Angeles, but never here. To see them in the Sierras, take my advice: stake out a viewing spot along Highway 41.

-- Jamie Simons

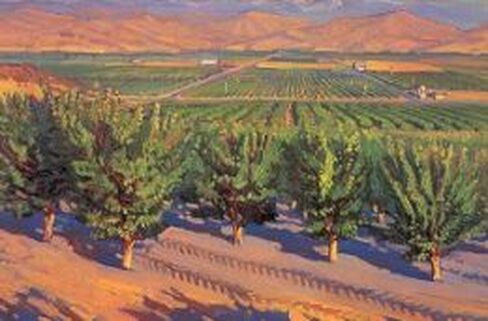

05/18/2011 Year in Yosemite: Farm Animal

One day last week, my husband, my daughter Karis and I were taking a walk down the road by our house in Yosemite National Park when we came across a family of deer happily munching on grass. "Oh," sighed Karis. "Don't you wish we were like the deer and could find food so easily? Then we wouldn't have the hassle of driving to Oakhurst."

Being the annoying kind of parents that can't let any innocent comment go untouched, my husband pointed out that when it snows, the deer don't find it easy either. While I felt it necessary to take things to a whole new level by talking about how the Indian peoples who lived in the Yosemite area for 10,000 years were able to collect two year's worth of acorns — their main food source — in just two weeks.* My husband and I may have been busy turning a simple walk into a series of teaching moments, but in my heart of hearts, my daughter had me. Why did we have to drive over an hour round-trip down to Oakhurst at least once a week (and make the three-hour round-trip to Fresno at least once a month for all-important, happiness-sustaining visits to Trader Joe's and Costco)?

Shortly thereafter, I went to a party where a female ranger and a ranger's wife were rhapsodizing about "the box" — a once-a-week delivery of organic fruits and vegetables that comes right to your door (thanks to a community-organized pick-up system). The produce comes from T&D Willey Farms, a Madera-based community-supported-agriculture farm that supplies everyone from Alice Waters at Chez Panisse to, well, my neighbors. That all sounded fine, in fact very impressive, but, in truth, it was the women's clear eyes and perfect skin that made me come home and immediately order the box. (We'll ignore the fact that they are both twenty-plus years younger than I am.)

This week we had our first box experience. Peeling back the wrapper with the excitement of children on Christmas morning, we discovered sugar snap peas, summer crisp lettuce, red chard, spring onions, parsley, Camerosa strawberries and a vegetable called kohlrabi that looked like a Dr. Seuss design. Now what to do? We had one week to make use of everything in the box or be deluged with more. I felt like Lucy Ricardo at the chocolate factory.

The sugar snap peas and strawberries were easy. My daughter took them to school for snacks. We're salad freaks, so we dispensed of the lettuce quickly and I make chard tacos just about every week, so that had a purpose, too. Then there was the kohlrabi. Having never seen it before, I didn't have a clue how to cook it. I went on-line for recipes, then resorted to the advice of other "box" users — when all else fails, roast it — which is exactly what we did. Separating the greens from the bulbs, I threw them in with the spring onion, sprinkled it with Spike (my one cooking necessity, I'm hopeless in the kitchen without it), then poured on the olive oil. When everything crisped up, my daughter and I stood over the pan and shoveled the results in our mouths, oohing and aahing the whole time.

One day last week, my husband, my daughter Karis and I were taking a walk down the road by our house in Yosemite National Park when we came across a family of deer happily munching on grass. "Oh," sighed Karis. "Don't you wish we were like the deer and could find food so easily? Then we wouldn't have the hassle of driving to Oakhurst."

Being the annoying kind of parents that can't let any innocent comment go untouched, my husband pointed out that when it snows, the deer don't find it easy either. While I felt it necessary to take things to a whole new level by talking about how the Indian peoples who lived in the Yosemite area for 10,000 years were able to collect two year's worth of acorns — their main food source — in just two weeks.* My husband and I may have been busy turning a simple walk into a series of teaching moments, but in my heart of hearts, my daughter had me. Why did we have to drive over an hour round-trip down to Oakhurst at least once a week (and make the three-hour round-trip to Fresno at least once a month for all-important, happiness-sustaining visits to Trader Joe's and Costco)?

Shortly thereafter, I went to a party where a female ranger and a ranger's wife were rhapsodizing about "the box" — a once-a-week delivery of organic fruits and vegetables that comes right to your door (thanks to a community-organized pick-up system). The produce comes from T&D Willey Farms, a Madera-based community-supported-agriculture farm that supplies everyone from Alice Waters at Chez Panisse to, well, my neighbors. That all sounded fine, in fact very impressive, but, in truth, it was the women's clear eyes and perfect skin that made me come home and immediately order the box. (We'll ignore the fact that they are both twenty-plus years younger than I am.)

This week we had our first box experience. Peeling back the wrapper with the excitement of children on Christmas morning, we discovered sugar snap peas, summer crisp lettuce, red chard, spring onions, parsley, Camerosa strawberries and a vegetable called kohlrabi that looked like a Dr. Seuss design. Now what to do? We had one week to make use of everything in the box or be deluged with more. I felt like Lucy Ricardo at the chocolate factory.

The sugar snap peas and strawberries were easy. My daughter took them to school for snacks. We're salad freaks, so we dispensed of the lettuce quickly and I make chard tacos just about every week, so that had a purpose, too. Then there was the kohlrabi. Having never seen it before, I didn't have a clue how to cook it. I went on-line for recipes, then resorted to the advice of other "box" users — when all else fails, roast it — which is exactly what we did. Separating the greens from the bulbs, I threw them in with the spring onion, sprinkled it with Spike (my one cooking necessity, I'm hopeless in the kitchen without it), then poured on the olive oil. When everything crisped up, my daughter and I stood over the pan and shoveled the results in our mouths, oohing and aahing the whole time.

Then we turned our attention to the bulbs. Their exterior skin is tough and sinewy. Four knives, a cleaver and a vegetable peeler later, we finally wrestled them to the ground, leaving us with something soft enough to be cut into slices, sprinkled with Spike, (I don’t own stock, I promise), and covered with enough olive oil to keep a small fleet of biofuel cars going for a week. The result was lip-smacking delicious.

But here's the thing. Had I been a Miwok Indian living in Yosemite Valley, I would have fallen into the category of cooks who removed the nasty tasting tannin in their acorns by burying them whole in mud for several months. I am not a labor-intensive-type of chef. No removing the acorn hulls, grinding the meat into flour and endless leaching for me. I want to be like a deer, just scratching for food on the ground outside my door.

Maybe that's why I can't stop perusing the newsletter that accompanies "the box." Seems that eggs, milk, cheese, stone fruit, meat, olive oil, coffee, rice, juice and nuts can also be delivered to one's door. And while I love the ease of that as well as the whole organic, grass-fed, family-farm, simple life vibe, I'm hoping that if they send another vegetable like kohlrabi, they send Alice Waters too.

*The Natural World of the California Indians, Robert Heizer and Albert Elsasser, University of California Press, pgs. 95,96

(Photos courtesy T&D Willey Farms.)

--Jamie Simons

But here's the thing. Had I been a Miwok Indian living in Yosemite Valley, I would have fallen into the category of cooks who removed the nasty tasting tannin in their acorns by burying them whole in mud for several months. I am not a labor-intensive-type of chef. No removing the acorn hulls, grinding the meat into flour and endless leaching for me. I want to be like a deer, just scratching for food on the ground outside my door.

Maybe that's why I can't stop perusing the newsletter that accompanies "the box." Seems that eggs, milk, cheese, stone fruit, meat, olive oil, coffee, rice, juice and nuts can also be delivered to one's door. And while I love the ease of that as well as the whole organic, grass-fed, family-farm, simple life vibe, I'm hoping that if they send another vegetable like kohlrabi, they send Alice Waters too.

*The Natural World of the California Indians, Robert Heizer and Albert Elsasser, University of California Press, pgs. 95,96

(Photos courtesy T&D Willey Farms.)

--Jamie Simons

The neighbors. Photo credit: Nancy Casolaro.

The neighbors. Photo credit: Nancy Casolaro.

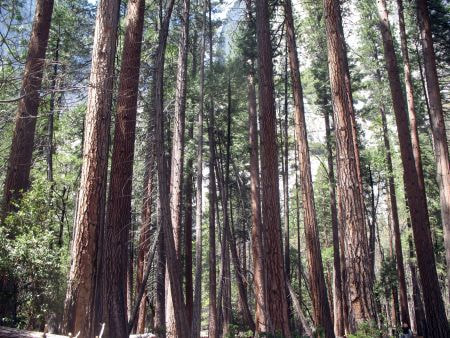

05/27/2011 Year in Yosemite: Zen Garden

Over the centuries, the Japanese have refined the art of the meditation garden. It usually involves a sentinel stone that symbolizes the Buddha and carefully raked smaller stones that represent everything from children to small animals to elves. So delicate and profound are the designs that these gardens are not to be entered. A bench is provided for meditation. Contemplation is the name of the game.

If you come to Yosemite National Park at this time of year, you can see Zen gardening Western style. There's nothing delicate about it. We're raking, but it's not stones and gravel being arranged to tell a story. No, this is big, brawny work that results in huge, massive piles of pine needles sitting helter skelter by the side of the road waiting for front loaders to come pick them up. If there is contemplation involved (and there is) it doesn't come from sitting and reflecting. It comes from taking action. Having a bad day? Grab a rake and go for it. The repetitive nature of the movement is sure to calm you down. Better yet, satisfaction is virtually instantaneous. It takes just minutes to pull the needles into large piles. Unfortunately, moving those piles from behind the house to the front of the house is not so satisfying. That's when another form of reflection comes in — how do I get my children to do this? Which would be more effective — the carrot or the stick?

So what's up with the piles? Well, nature may see them as part of the life cycle of a pine tree, but in Wawona they are seen as fuel. We live with thousands of pine trees so by summer, the ground around our homes is piled high with millions of needles. They are dry as brittle bones and fires, especially the out-of-control kind, love them. Hence, all the raking and loading. Last year, the county of Mariposa picked up enough pine needles to fill a football field. Wading across that stadium, you would have been four feet deep in needles. And that's just from Wawona, a place so tiny the word village is an exaggeration. We're really more like a hamlet — just a scattering of houses anchored by a library and a school.

Over the centuries, the Japanese have refined the art of the meditation garden. It usually involves a sentinel stone that symbolizes the Buddha and carefully raked smaller stones that represent everything from children to small animals to elves. So delicate and profound are the designs that these gardens are not to be entered. A bench is provided for meditation. Contemplation is the name of the game.

If you come to Yosemite National Park at this time of year, you can see Zen gardening Western style. There's nothing delicate about it. We're raking, but it's not stones and gravel being arranged to tell a story. No, this is big, brawny work that results in huge, massive piles of pine needles sitting helter skelter by the side of the road waiting for front loaders to come pick them up. If there is contemplation involved (and there is) it doesn't come from sitting and reflecting. It comes from taking action. Having a bad day? Grab a rake and go for it. The repetitive nature of the movement is sure to calm you down. Better yet, satisfaction is virtually instantaneous. It takes just minutes to pull the needles into large piles. Unfortunately, moving those piles from behind the house to the front of the house is not so satisfying. That's when another form of reflection comes in — how do I get my children to do this? Which would be more effective — the carrot or the stick?

So what's up with the piles? Well, nature may see them as part of the life cycle of a pine tree, but in Wawona they are seen as fuel. We live with thousands of pine trees so by summer, the ground around our homes is piled high with millions of needles. They are dry as brittle bones and fires, especially the out-of-control kind, love them. Hence, all the raking and loading. Last year, the county of Mariposa picked up enough pine needles to fill a football field. Wading across that stadium, you would have been four feet deep in needles. And that's just from Wawona, a place so tiny the word village is an exaggeration. We're really more like a hamlet — just a scattering of houses anchored by a library and a school.

Photo credit: Jon Jay.

Photo credit: Jon Jay.

So what happens to our needles? They burn them. Send them up in smoke, but in a very controlled way. Hearing that, I began to wonder if there were more creative uses for pine needles. Turns out there are. The Indian peoples who inhabited the area for thousands of years used them in all sorts of ways — from making exquisite pine needle baskets to making tea so rich in vitamin C it could cure scurvy. Local inhabitants (Indian* and otherwise) still use pine needles to make baskets, line their chicken coops, and to mulch their strawberries and other acid-loving plants.

Which led me to wonder if poor, cash-strapped Mariposa County could become the pine needle capital of the world. Think of the money we could bring in with our Paul Bunyan-size needle piles. Nope said the county. Seems it costs a fortune to get anything out of Yosemite National Park. Too far to drive. Too many fuel costs. Too big a hassle. (And they were kind enough not to add "too insane an idea").

I also learned that for a number of public policy reasons, the pine needle program may be on its last legs. If they are not going to be picked up, what are we going to do with all that spontaneously combustible fuel? Once my "pine needle capital of the world" idea went up in smoke, I didn't have an answer.

But I do know this. The Indians who lived here before us didn't have a pine needle problem. Ten thousand years before we came up with the practice of controlled burns, they regularly let nature have its way with fire. The result was healthier ecosystems and no pesky ground fuel. Of course, that's easy when the trees (and all those needles) don't surround structures you want to live and work in. Seems they had an answer for that, too. In Yosemite Valley, where their own homes sat, they burnt the forests to the ground to turn them into meadows. What likes meadows? Oak trees and deer—happily two of the locals' favorite foods. Obviously, this is no longer an option. Still, it makes me wonder if, while the forests burned, the Miwok people sat quietly watching, lost in deep reflective contemplation.

*Forgive me if I'm wrong, but I use the term Indian peoples or Indians because my Indian friends tell me they prefer it to Native-American. I’m just trying to follow their lead.

-- Jamie Simons

Which led me to wonder if poor, cash-strapped Mariposa County could become the pine needle capital of the world. Think of the money we could bring in with our Paul Bunyan-size needle piles. Nope said the county. Seems it costs a fortune to get anything out of Yosemite National Park. Too far to drive. Too many fuel costs. Too big a hassle. (And they were kind enough not to add "too insane an idea").

I also learned that for a number of public policy reasons, the pine needle program may be on its last legs. If they are not going to be picked up, what are we going to do with all that spontaneously combustible fuel? Once my "pine needle capital of the world" idea went up in smoke, I didn't have an answer.

But I do know this. The Indians who lived here before us didn't have a pine needle problem. Ten thousand years before we came up with the practice of controlled burns, they regularly let nature have its way with fire. The result was healthier ecosystems and no pesky ground fuel. Of course, that's easy when the trees (and all those needles) don't surround structures you want to live and work in. Seems they had an answer for that, too. In Yosemite Valley, where their own homes sat, they burnt the forests to the ground to turn them into meadows. What likes meadows? Oak trees and deer—happily two of the locals' favorite foods. Obviously, this is no longer an option. Still, it makes me wonder if, while the forests burned, the Miwok people sat quietly watching, lost in deep reflective contemplation.

*Forgive me if I'm wrong, but I use the term Indian peoples or Indians because my Indian friends tell me they prefer it to Native-American. I’m just trying to follow their lead.

-- Jamie Simons

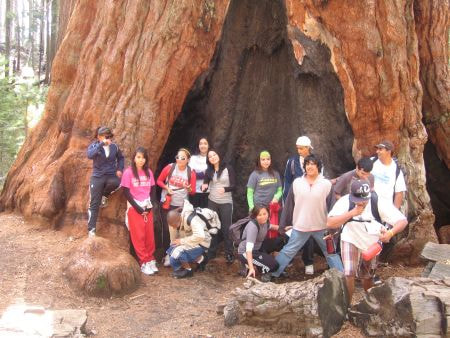

06/10/2011 Year in Yosemite: In the Footsteps of Giants

ARC students with Giant Sequoia.

At the top of a trail just up the hill from our house in Yosemite National Park stands the Mariposa Grove of Giant Sequoias. With over 500 of the world's largest sequoia trees, it is a must-see for most visitors to the park. But while standing next to a mature sequoia can leave one slack-jawed with wonder, it's their cones that fascinate me. Because the largest living thing on Earth starts its life in the tiniest, simplest way. Its seed is just the size of an oat. Its cone is less than three inches long. Its needs are profound — only the right mixture of sun, soil, and water as well as help from hungry chickarees, boring beetles or fire will allow these massive trees to get a start in life.

This week the teenagers participating in the Adventure Risk Challenge (ARC) program at Yosemite will move into their home base at my daughter's school. Many of them are only fourteen-years-old. Over the next forty days they will hike, backpack, river raft, rock climb, and more importantly, learn to rely on themselves and each other. Most of them are from families where English is the second language. Many of them attend knowing they are their family's hope for a different kind of life. It is up to these kids to learn the skills that will take them to college and their families from agricultural work in the Central Valley into the mainstream of American life. Their journey reminds me of the sequoias.

Like the sequoia's cones, they are chockfull of the gifts of life — in their case, talent, smarts, kindness, hope and a willingness to work hard. But like the giant trees, they will need just the right mixture of conditions to flourish. By teaching wilderness skills, leadership training and putting the students through a rigorous writing curriculum, ARC, a program sponsored by the University of California at Berkeley and Merced (but funded by private donations), hopes to provide just that. I know it can happen because I've watched many ARC participants grow and mature in this program, going from high school kids showing promise to successful students at top universities.

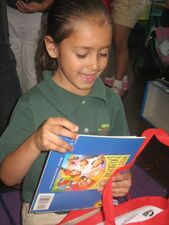

The last time I did a writing workshop with the ARC students, the topic was service. All through the class I wanted to share my friend Nancy Casolaro’s story. For whatever reason, I refrained. Then last Sunday I spent the day at Nancy's helping to put books into book bags for kids at an inner city school. Three years ago, Nancy and another friend, Sarina Simon, took it upon themselves to adopt an inner-city KIP school (of Waiting for Superman fame). The principal's main request? Help get books to the students, many of whom had never owned even one. Using their own money and Nancy's considerable bargain-hunting skills, Project Bookbag was born. Each year they have given every student in the school a bag containing seven too-good-to-put-down books.

ARC students with Giant Sequoia.

At the top of a trail just up the hill from our house in Yosemite National Park stands the Mariposa Grove of Giant Sequoias. With over 500 of the world's largest sequoia trees, it is a must-see for most visitors to the park. But while standing next to a mature sequoia can leave one slack-jawed with wonder, it's their cones that fascinate me. Because the largest living thing on Earth starts its life in the tiniest, simplest way. Its seed is just the size of an oat. Its cone is less than three inches long. Its needs are profound — only the right mixture of sun, soil, and water as well as help from hungry chickarees, boring beetles or fire will allow these massive trees to get a start in life.

This week the teenagers participating in the Adventure Risk Challenge (ARC) program at Yosemite will move into their home base at my daughter's school. Many of them are only fourteen-years-old. Over the next forty days they will hike, backpack, river raft, rock climb, and more importantly, learn to rely on themselves and each other. Most of them are from families where English is the second language. Many of them attend knowing they are their family's hope for a different kind of life. It is up to these kids to learn the skills that will take them to college and their families from agricultural work in the Central Valley into the mainstream of American life. Their journey reminds me of the sequoias.

Like the sequoia's cones, they are chockfull of the gifts of life — in their case, talent, smarts, kindness, hope and a willingness to work hard. But like the giant trees, they will need just the right mixture of conditions to flourish. By teaching wilderness skills, leadership training and putting the students through a rigorous writing curriculum, ARC, a program sponsored by the University of California at Berkeley and Merced (but funded by private donations), hopes to provide just that. I know it can happen because I've watched many ARC participants grow and mature in this program, going from high school kids showing promise to successful students at top universities.

The last time I did a writing workshop with the ARC students, the topic was service. All through the class I wanted to share my friend Nancy Casolaro’s story. For whatever reason, I refrained. Then last Sunday I spent the day at Nancy's helping to put books into book bags for kids at an inner city school. Three years ago, Nancy and another friend, Sarina Simon, took it upon themselves to adopt an inner-city KIP school (of Waiting for Superman fame). The principal's main request? Help get books to the students, many of whom had never owned even one. Using their own money and Nancy's considerable bargain-hunting skills, Project Bookbag was born. Each year they have given every student in the school a bag containing seven too-good-to-put-down books.

Project Bookbag day at school.

Project Bookbag day at school.

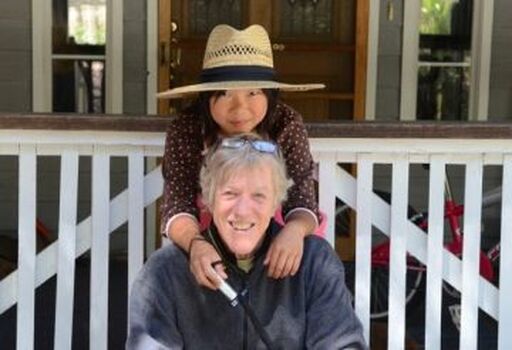

For Nancy this is personal. The child of first-generation Italian immigrants, her father never finished grammar school; her mother had to drop out of high school (and later earned her GED). There were no books in their home. But they had a neighbor, Doug McGall, who worked in a bookstore. He made it his business to read to Nancy, her brother and her cousins and to give them books.

Doug McGall died when Nancy was in the second grade, but he left money for Nancy, her brother and her cousins to go to college. Nancy's brother grew up to be one of the country’s most famous prosecutors. Nancy has devoted her life to education. They still credit Doug McGall with instilling in them a love of learning. Now Nancy is passing on the gift.

Doug McGall died when Nancy was in the second grade, but he left money for Nancy, her brother and her cousins to go to college. Nancy's brother grew up to be one of the country’s most famous prosecutors. Nancy has devoted her life to education. They still credit Doug McGall with instilling in them a love of learning. Now Nancy is passing on the gift.

(Picture: Doug McGall and Nancy.)

(Picture: Doug McGall and Nancy.)

Later this week, I’ll meet the students who will spend their forty days in the wilderness learning to be more than they ever hoped they could be. I hope to share with them the story of Doug McGall. Actions don’t have to be huge to make a difference. Service can pay off decades after the original deed. Like the towering sequoia, great things can happen from even the tiniest seed.

-- Jamie Simons

-- Jamie Simons

09/21/2011 Year in Yosemite: Love Story

This past summer my family and I left our home in Yosemite National Park to take a 3000-mile round trip to Yellowstone, Grand Teton, Zion and Death Valley National Parks. Here's what I learned: Ignore the TV. Turn off the radio, the iPad and the cell phone. Don't read magazine or newspaper articles. Ignore the constant drumbeat of doom and gloom, the drone of best-guess pundits, the stifling undercurrent of fear that seems to consume America these days. Instead, get in the car, (preferably a hybrid) and start driving. In our case, we headed northeast to the huge open swathes of land that make up northern Nevada, Idaho, Montana and Wyoming. I'm not convinced it matters where you go. What seems to matter is really seeing our country and our people, because when I did, I found myself falling deeply in love with America.

This past summer my family and I left our home in Yosemite National Park to take a 3000-mile round trip to Yellowstone, Grand Teton, Zion and Death Valley National Parks. Here's what I learned: Ignore the TV. Turn off the radio, the iPad and the cell phone. Don't read magazine or newspaper articles. Ignore the constant drumbeat of doom and gloom, the drone of best-guess pundits, the stifling undercurrent of fear that seems to consume America these days. Instead, get in the car, (preferably a hybrid) and start driving. In our case, we headed northeast to the huge open swathes of land that make up northern Nevada, Idaho, Montana and Wyoming. I'm not convinced it matters where you go. What seems to matter is really seeing our country and our people, because when I did, I found myself falling deeply in love with America.

For starters, Americans are nice. Really nice. From the Hell's Angel biker who ran out of a restaurant in Cody, Wyoming to return my sweater to the junior high school counselor from San Diego who was waiting tables at Yellowstone's Pahaska Tepee, Americans go out of their way to be helpful. We like good stories. We like to share. When a need arises, we watch out for one another. When not whipped into a negative frenzy, we're funny and kind.

Maybe it's the West. Maybe it's the great, rolling splendor of the land, but to me, America looked vibrant and healthy -- a country rich with resources. And I'm not just talking about the national parks. Right outside of Elko, Nevada -- which will never make anyone's bucket list of places they have to see before they die -- the sky turned black with thunder clouds, lightning filled the air and a double rainbow grew before us, stretching from the earth to the sky. Maybe someone should rethink that list -- even Elko is capable of offering moments of startling beauty.

Maybe it's the West. Maybe it's the great, rolling splendor of the land, but to me, America looked vibrant and healthy -- a country rich with resources. And I'm not just talking about the national parks. Right outside of Elko, Nevada -- which will never make anyone's bucket list of places they have to see before they die -- the sky turned black with thunder clouds, lightning filled the air and a double rainbow grew before us, stretching from the earth to the sky. Maybe someone should rethink that list -- even Elko is capable of offering moments of startling beauty.

My very first trip around the West was thirty years ago with a friend from Germany. While anyone who's ever been to Europe knows it's hard to compete with the charm of its villages, towns and cities, she was wide-eyed at the beauty of America's “wilderness.” She couldn't believe there could be so much land filled, not with the 60 million buffalo America’s native peoples knew, but with enough bison and grizzlies and pronghorn to still make her slack-jawed with envy. Traveling with her, I came to understand something the rest of the world seems to get instinctively -- Yellowstone is our Eiffel Tower, Zion is our Chartres Cathedral, Yosemite is our Tower of London. But better. Being part of nature, they reach out and touch some primordial piece of us. They become emblazoned in our memories.

We took this trip because when my husband was 12, he and his mother and father got in a car (definitely not a hybrid), and drove from Philadelphia through the Black Hills to Yellowstone and Grand Teton parks. Now that our daughter is just about that age, he wanted to share these places with her. More than fifty years after he first made the journey, America did not disappoint. And while Yellowstone, the Grand Tetons, Zion and the other magnificent national parks are one of America’s better ideas; to me, it’s Americans -- with our kindness, our humor and, at our best, a reverence for the land -- that makes us great.

(Photos credit: Jon Jay.)

-- Jamie Simons

(Photos credit: Jon Jay.)

-- Jamie Simons

Grand Tetons National Park

Grand Tetons National Park

09/29/2011 Year in Yosemite: Redux

Grand Teton National Park.

This is the start of our third year of living inside Yosemite National Park. I'm happy here but, truth be told, it's not my favorite national park. I haven't had the good fortune to visit them all, but of the many I've seen, the one that calls me back again and again is Zion. Like a pilgrim to Mecca, I make it a point to visit there yearly. I never tire of its grandeur. But I make no apologies for my wayward affections. The National Park Service rangers we live among taught me that.

Grand Teton National Park.

This is the start of our third year of living inside Yosemite National Park. I'm happy here but, truth be told, it's not my favorite national park. I haven't had the good fortune to visit them all, but of the many I've seen, the one that calls me back again and again is Zion. Like a pilgrim to Mecca, I make it a point to visit there yearly. I never tire of its grandeur. But I make no apologies for my wayward affections. The National Park Service rangers we live among taught me that.

Yellowstone National Park

Yellowstone National Park

These are people who have decided to devote their lives to the national parks. It sounds romantic, but it comes at no small cost. Not only is the pay ridiculously low, but getting a permanent job in a national park takes all but an act of Congress. And so rangers move around ... a lot. At first (hopefully when they are young and without families), they take any seasonal work that comes their way, no matter where it is.

After living out of a suitcase and changing jobs and locations every six months (sometimes for years), with luck they'll be offered a full-time position. It may not be at the park of their choice, but so few are the opportunities for permanent status (as it's called), that people grab it anyway.

After living out of a suitcase and changing jobs and locations every six months (sometimes for years), with luck they'll be offered a full-time position. It may not be at the park of their choice, but so few are the opportunities for permanent status (as it's called), that people grab it anyway.

A moose in Grand Teton.

A moose in Grand Teton.

So you might work in Yosemite or the Everglades or Big Bend or the Black Hills, but it may not be where you really want to be. Perhaps it's the parks of the Olympic peninsula that touch your soul or the volcanoes of Hawaii's Big Island or even an historic park in a city center. But rangers go where the jobs are and they’ll stay until an opportunity for moving up sends them on to their next posting. That’s kind of how I am with Yosemite. I recognize that I'm unbelievably lucky to be able to call it home and yet (don’t hate me Yosemite lovers) I've always felt it wouldn’t make my personal list of top five parks ... until this summer.

In July we took a road trip, visiting four other national parks along the way. Suddenly I found myself behaving like a mother on her child’s first day of kindergarten. Standing in awe before the magnificent beauty of Yellowstone, with its shooting geysers, buffalo herds, wildflower-covered wilderness, and massive waterfalls, I was like the parent who looks around the classroom wondering, “Will my child be able to make the grade? Does she have what it takes?” At one point I actually asked my husband, “Can Yosemite hold a candle to this?”

In July we took a road trip, visiting four other national parks along the way. Suddenly I found myself behaving like a mother on her child’s first day of kindergarten. Standing in awe before the magnificent beauty of Yellowstone, with its shooting geysers, buffalo herds, wildflower-covered wilderness, and massive waterfalls, I was like the parent who looks around the classroom wondering, “Will my child be able to make the grade? Does she have what it takes?” At one point I actually asked my husband, “Can Yosemite hold a candle to this?”

Zion National Park

Zion National Park

My anxiety deepened as we traveled down to Grand Teton National Park. Magnificent seems a paltry word to describe the Tetons’ meeting of land and water. Newly carved (in geological time), like a precocious child, the youngest mountains in the Rockies demand that you give them your full attention. Add to their beauty the sun shimmering on Lake Jackson, the elk-filled willow flats, the moose grazing on the shore as bald eagles fly overhead and the only thing left to say is “OMG!”

Now I know that countless millions of people have stood at the lookout at Yosemite’s Tunnel View and cried “OMG!” In truth, what other reaction could you have? But as we traveled on to my beloved Zion and then cut across Death Valley to get home, I still wondered, and even worried, if Yosemite would be able to make the grade.

I had my answer when we drove over Tioga Pass, passed by Tuolumne Meadows, skirted the edge of Tenaya Lake, and dropped down into Yosemite Valley. I was giddy with delight. No revelation to anyone else -- but a major breakthrough for me -- with its soaring granite towers and gushing waterfalls, Yosemite seemed the very epitome of nature’s

Now I know that countless millions of people have stood at the lookout at Yosemite’s Tunnel View and cried “OMG!” In truth, what other reaction could you have? But as we traveled on to my beloved Zion and then cut across Death Valley to get home, I still wondered, and even worried, if Yosemite would be able to make the grade.

I had my answer when we drove over Tioga Pass, passed by Tuolumne Meadows, skirted the edge of Tenaya Lake, and dropped down into Yosemite Valley. I was giddy with delight. No revelation to anyone else -- but a major breakthrough for me -- with its soaring granite towers and gushing waterfalls, Yosemite seemed the very epitome of nature’s

Yosemite

Yosemite

power. Not only did we hold our own, we triumphed. Of course, this could only mean one thing. Some how, some way, without my even realizing it, I had fallen deeply in love with where we live.

Yosemite had moved to the top of my list (okay, maybe still behind Zion) -- but way up there. My mother always says that the bond between a parent and child is not about genes but about time put in. If that’s the case, as we start our third year here I realize how deeply I feel connected to this place. Yellowstone, Grand Teton, Zion, and Death Valley cast a splendor all their own. But this is truly home.

(Top photo of Grand Teton by Karis Simons. All other photos by Jon Jay.)

-- Jamie Simons

Yosemite had moved to the top of my list (okay, maybe still behind Zion) -- but way up there. My mother always says that the bond between a parent and child is not about genes but about time put in. If that’s the case, as we start our third year here I realize how deeply I feel connected to this place. Yellowstone, Grand Teton, Zion, and Death Valley cast a splendor all their own. But this is truly home.

(Top photo of Grand Teton by Karis Simons. All other photos by Jon Jay.)

-- Jamie Simons

The California Tunnel Tree. Tunnel was carved through the tree in 1895 as a way to promote the grove. Originally, it could accommodate a car. Since that time, the bark has been growing inward in an attempt to close its wound.

The California Tunnel Tree. Tunnel was carved through the tree in 1895 as a way to promote the grove. Originally, it could accommodate a car. Since that time, the bark has been growing inward in an attempt to close its wound.

10/06/2011 Year in Yosemite: A Walk with Giants

Things move slowly around here. On October 13, 2010 the Fossil Discovery Center of Madera County finally opened its doors. It took 17 years to plan and build. The museum celebrates the era when massive wooly mammoths, saber tooth cats and dire wolves roamed the region. Last Thursday, I joined two friends and spent the day wandering among the last living relics of that time.

Located just up the hill from our home in Yosemite National Park, the giant sequoias of the Mariposa Grove represent just a tiny slice of the massive forests of sequoias that scientists believe once stretched across this part of California. Their growth is even slower than that of the Fossil Discovery Center. Stretching up and out at a rate of just inches a year, it has taken some of these beauties almost 3,000 years to reach their present girth and height. It was worth the wait. As their heartfelt guardian Galen Clark wrote more than 100 years ago, "Here it seems one is standing in a great temple, silent, restful, with the air seemingly filled with eternal peace."

Things move slowly around here. On October 13, 2010 the Fossil Discovery Center of Madera County finally opened its doors. It took 17 years to plan and build. The museum celebrates the era when massive wooly mammoths, saber tooth cats and dire wolves roamed the region. Last Thursday, I joined two friends and spent the day wandering among the last living relics of that time.

Located just up the hill from our home in Yosemite National Park, the giant sequoias of the Mariposa Grove represent just a tiny slice of the massive forests of sequoias that scientists believe once stretched across this part of California. Their growth is even slower than that of the Fossil Discovery Center. Stretching up and out at a rate of just inches a year, it has taken some of these beauties almost 3,000 years to reach their present girth and height. It was worth the wait. As their heartfelt guardian Galen Clark wrote more than 100 years ago, "Here it seems one is standing in a great temple, silent, restful, with the air seemingly filled with eternal peace."

The Grizzly Giant. The first branch on the right has grown vertically. Its diameter is larger than the trunk of any non sequoia in the grove.

The Grizzly Giant. The first branch on the right has grown vertically. Its diameter is larger than the trunk of any non sequoia in the grove.

Not everyone saw it that way. Just a couple of miles away, in an area now called the Nelder Grove, the Madera Flume and Trading Company tried logging these giants. The results were disastrous. The trunks were so massive that it took days and several men with massive saws to cut down a single tree. When the sequoia fell, the ground shook with the intensity of an earthquake, shattering the tree into thousands of pieces -- useful for making only shingles, pencils and matchsticks.

Before speculators like the Madera Flume and Trading Company bought the land, the native peoples of the Sierra Nevada had respected the sequoia groves as sacred ground. Galen Clark saw them that way too. Exploring the Mariposa Grove for the first time in 1857, he became fairly obsessed with saving it. The idea was radical and new. No one in the history of the world had ever set aside land simply to protect and preserve it for all people, for all time. Yet, just seven years after Clark first laid eyes on the Mariposa Grove, Abraham Lincoln signed a land grant protecting it and Yosemite Valley from development.

Trio of Sequoias on the right dwarf neighboring trees. All photos by Jon Jay.

Ever since, people have been debating exactly what that means. Where does the balance between preservation, public enjoyment, and taking care of visitors' needs lie? What is it that has value? Access or true wilderness?

Wandering through the sequoia groves on a warm autumn day, I did not think of any of this. Like Mr. Clark, I stood "filled with a sense of awe and veneration, as if treading on hallowed ground."

Before speculators like the Madera Flume and Trading Company bought the land, the native peoples of the Sierra Nevada had respected the sequoia groves as sacred ground. Galen Clark saw them that way too. Exploring the Mariposa Grove for the first time in 1857, he became fairly obsessed with saving it. The idea was radical and new. No one in the history of the world had ever set aside land simply to protect and preserve it for all people, for all time. Yet, just seven years after Clark first laid eyes on the Mariposa Grove, Abraham Lincoln signed a land grant protecting it and Yosemite Valley from development.

Trio of Sequoias on the right dwarf neighboring trees. All photos by Jon Jay.

Ever since, people have been debating exactly what that means. Where does the balance between preservation, public enjoyment, and taking care of visitors' needs lie? What is it that has value? Access or true wilderness?

Wandering through the sequoia groves on a warm autumn day, I did not think of any of this. Like Mr. Clark, I stood "filled with a sense of awe and veneration, as if treading on hallowed ground."

Trio of Sequoias on the right dwarf neighboring trees. All photos by Jon Jay

Trio of Sequoias on the right dwarf neighboring trees. All photos by Jon Jay

But while I felt blessed to be walking among these ancient giants, the pragmatic side of me realized that, like the saber tooth cats and the wooly mammoth, the Madera Flume and Trading Company is extinct. Mariposa County (which encompasses a great deal of Yosemite National Park) has seen logging companies, gold rush prospectors, and cattle ranchers all move on. Without the park, it would be as bereft of funds as the counties that surround it. It is almost completely dependent for its economic survival on the tourists that Yosemite National Park attracts. Which begs the question, was Galen Clark an enlightened preservationist or an economic genius?

-- Jamie Simons

-- Jamie Simons

After roasting our acorns, we extracted the seeds and ground them into a fine flour. This Valley Oak acorn is among the few that aren't bitter.

After roasting our acorns, we extracted the seeds and ground them into a fine flour. This Valley Oak acorn is among the few that aren't bitter.

10/13/2011 Year in Yosemite: Native Genius

I spent the day yesterday leaching acorns and learning to make acorn mush. It's not what I usually serve to family and friends in our Yosemite home but I can't remember the last time cooking was so much fun. This is the time of year when traditionally, Miwok and other native tribes of the region would have been collecting enough acorns -- 1,000 to 2,000 pounds per family -- to keep them in food for a year. The Miwok would have spent two weeks filling massive baskets with acorns but we took the easy way out. We had a group of school kids collect one bag each from around their neighborhoods in Oakhurst, Mariposa, and Fresno and bring them to us to be leached.

Tonight these same kids will come to Yosemite National Park and make their way to a private camp, Camp Wawona, for their first foray into a world that's virtually disappeared from sight. For one night and a day they will get to experience a tiny piece of what Yosemite was like for the native peoples who thought of it as their three-season home for over 3,000 years. In the short time that the students are here, they will experience what it took to find shelter, food, clothing and warmth using only what nature provides.

Yesterday, my husband and I were at the camp to help the staff get ready for the group that's about to descend on them. Even after a lifetime spent hiking, camping, and backpacking (with the help of JanSport, North Face and REI), I was surprised to learn that nature provides absolutely everything needed to get the job done -- manmade materials need not apply.

I spent the day yesterday leaching acorns and learning to make acorn mush. It's not what I usually serve to family and friends in our Yosemite home but I can't remember the last time cooking was so much fun. This is the time of year when traditionally, Miwok and other native tribes of the region would have been collecting enough acorns -- 1,000 to 2,000 pounds per family -- to keep them in food for a year. The Miwok would have spent two weeks filling massive baskets with acorns but we took the easy way out. We had a group of school kids collect one bag each from around their neighborhoods in Oakhurst, Mariposa, and Fresno and bring them to us to be leached.

Tonight these same kids will come to Yosemite National Park and make their way to a private camp, Camp Wawona, for their first foray into a world that's virtually disappeared from sight. For one night and a day they will get to experience a tiny piece of what Yosemite was like for the native peoples who thought of it as their three-season home for over 3,000 years. In the short time that the students are here, they will experience what it took to find shelter, food, clothing and warmth using only what nature provides.

Yesterday, my husband and I were at the camp to help the staff get ready for the group that's about to descend on them. Even after a lifetime spent hiking, camping, and backpacking (with the help of JanSport, North Face and REI), I was surprised to learn that nature provides absolutely everything needed to get the job done -- manmade materials need not apply.

But not all of our acorns were Valley Oak so we had to soak the flour in hot water (3-4 times) to leach out the bitter tannins. When the bitterness was gone, the mush was spread onto cookie sheets and baked into tasty crackers.

But not all of our acorns were Valley Oak so we had to soak the flour in hot water (3-4 times) to leach out the bitter tannins. When the bitterness was gone, the mush was spread onto cookie sheets and baked into tasty crackers.

Now I get that modern conveniences are just what the words say, modern and convenient. Truth be told, we were only able to create enough acorn crackers to feed 40 people because we used modern inventions. Instead of leaving the acorns out in the sun to dry, we put them in large, industrial-size ovens overnight at 200 degrees. While the Miwok would have used stones to crack them open, we used hammers. After the kernels were removed, the Miwok would have put them on grinding stones and hit them with rocks until they created acorn flour. (That's what the kids will do). Having use of a kitchen, we put them in a nut grinder, then moved them to a blender to get the fine acorn powder needed for cooking. We didn't sit by a river for hours at a time leaching out the bitter tannins. Our method was to simply boil water on the stove and pour it over the flour time after time until the bitter taste disappeared. Then we spread the wet mush onto cookie sheets, placed them in the oven, and minutes later had nutty-tasting acorn crackers rich in protein and fat, calcium, phosphorus, potassium, and niacin. It was terrific fun but it wasn’t what produced my aha moment.

With five people and a couple of minutes, we made a primitive friction fire with a bow and drill.

With five people and a couple of minutes, we made a primitive friction fire with a bow and drill.

That came from the cumulative experience of the day. Because, while the acorn mush was baking, we also made a protein-rich tea from the tips of incense cedars leaves. Then we picked out the very best shells left from the acorns and put them aside to make poultices to kill the itch caused by poison oak and mosquito bites. After that we moved outside to learn how to make fire using a wooden bow and drill. With five people working together, it took about two minutes to create a hot coal that we placed in a nest of incense cedar shavings and bark. When we blew on it, it erupted into flame. It seemed so amazing to me that I asked to do it again and again.

In one day, I learned that two trees -- oak and incense cedar -- can provide the majority of life's necessities. I can't wait to see the look on the kids' faces as they realize that just from the ground around their camp, they have everything they need to make hunting tools, build a shelter, make rope, start a fire, create food, even fashion a toothbrush.*

I came home from yesterday's training session entranced. I felt that for once, I was wowed, not by nature's power and beauty, but by its gentle, giving ways. The overnight at the Indian Camp is the kickoff for a year-long program that will start in the world of the indigenous people and end with an overnight at Wawona's Pioneer Village where this group of 5th through 8th graders will live as if the year were 1880 and Yosemite was just being "discovered" by all but the native peoples.

In one day, I learned that two trees -- oak and incense cedar -- can provide the majority of life's necessities. I can't wait to see the look on the kids' faces as they realize that just from the ground around their camp, they have everything they need to make hunting tools, build a shelter, make rope, start a fire, create food, even fashion a toothbrush.*

I came home from yesterday's training session entranced. I felt that for once, I was wowed, not by nature's power and beauty, but by its gentle, giving ways. The overnight at the Indian Camp is the kickoff for a year-long program that will start in the world of the indigenous people and end with an overnight at Wawona's Pioneer Village where this group of 5th through 8th graders will live as if the year were 1880 and Yosemite was just being "discovered" by all but the native peoples.

he umuucha was the typical shelter of Yosemite's Miwok Indians.

he umuucha was the typical shelter of Yosemite's Miwok Indians.

Several weekends ago a group of ten parents went through the park service training at the Pioneer Village so we would be ready to chaperon the kids when they come for their overnight this spring. I don't know the last time I learned so much or had so much fun ... until I trained for the Indian Camp. That Yosemite is special is something millions of people around the world know and acknowledge. That it came stocked with everything people and animals need to flourish without any outside help or inventions is something only the native people seemed to understand. I feel lucky to have experienced a modern interpretation of their way of life for even a nano-second. To live with respect, appreciation and gratitude for the natural world is the native peoples’ great teaching. With all the time I’ve spent in nature, I didn’t fully understand how beneficial and generous a gift that teaching was. Now I do.

*Nothing we use for the camp will be grown in Yosemite National Park. It’s all from private land.

-- Jamie Simons/Photos by Jon Jay

*Nothing we use for the camp will be grown in Yosemite National Park. It’s all from private land.

-- Jamie Simons/Photos by Jon Jay

The Wawona Golf Course was our nation's first organic course.

The Wawona Golf Course was our nation's first organic course.

11/02/2011 Year in Yosemite: Fore Ever

Yosemite National Park is one of the only national parks to host a golf course within its boundaries. For the public record, I own the sixth hole. Not own as in, I hit a hole-in-one there and now both the sixth hole and I are famous. I don’t golf. But I think of it as mine just the same. That’s because each year during Wawona Elementary School’s Golf Tournament and Fundraiser, it’s the place I sit waiting to witness someone else make a hole-in-one. If they do (and so far no one has), they instantly win a car. And while it would be thrilling to see someone win both the hole and the car, it’s not the reason I sign up for sixth-hole duty each year. Nope. My reasons have to do with its quiet and beauty and the sheer audacious resilience of the place.

Originally designed in 1917 for the Washburn brothers (the original owners of the Wawona Hotel), the Wawona Golf Course became part of Yosemite National Park when the Wawona Hotel and its surroundings were deeded to the federal government in 1932. More interested in wilderness than golf courses, the federal government found they couldn’t get rid of the course (it was there before they took ownership), but they could let it die of benign neglect. Which is exactly what they set out to do until a man named Kim Porter showed up in 1980. He became obsessed with restoring the nine-hole golf course to its former glory — no mean feat when it’s inside a national park.

Yosemite National Park is one of the only national parks to host a golf course within its boundaries. For the public record, I own the sixth hole. Not own as in, I hit a hole-in-one there and now both the sixth hole and I are famous. I don’t golf. But I think of it as mine just the same. That’s because each year during Wawona Elementary School’s Golf Tournament and Fundraiser, it’s the place I sit waiting to witness someone else make a hole-in-one. If they do (and so far no one has), they instantly win a car. And while it would be thrilling to see someone win both the hole and the car, it’s not the reason I sign up for sixth-hole duty each year. Nope. My reasons have to do with its quiet and beauty and the sheer audacious resilience of the place.

Originally designed in 1917 for the Washburn brothers (the original owners of the Wawona Hotel), the Wawona Golf Course became part of Yosemite National Park when the Wawona Hotel and its surroundings were deeded to the federal government in 1932. More interested in wilderness than golf courses, the federal government found they couldn’t get rid of the course (it was there before they took ownership), but they could let it die of benign neglect. Which is exactly what they set out to do until a man named Kim Porter showed up in 1980. He became obsessed with restoring the nine-hole golf course to its former glory — no mean feat when it’s inside a national park.

Clearly, using pesticides to restore the greens was out of the question, so he went organic, making Wawona the first organic golf course in the nation. He combined natural grasses to keep the fairways and greens healthy, relied on the area’s hawks, owls and eagles to keep the rodent population under control and watered it all with reclaimed water. Once the fairways and greens were in good working order, he turned to the wilderness, letting it take over any sections of the course that weren’t crucial to play. To me, one of the most beautiful sections of the course is, you got it, the sixth hole, where a restored riparian habitat sits side by side with a par-three hole.But I’m not the only one impressed by Kim Porter’s strategy. The Wawona Golf Course garnered the prestigious Audubon Cooperative Sanctuary Award, a nod to the fact that this ecologically correct piece of earth is beloved by golfers and non-golfers alike. Where else can you sit at the edge of a green and listen to wildlife (bears and mountain lions included) root around in the forest? Or watch deer mosey across the fairway between players? Or take a hike on a trail when your game is done? It seems fitting to me that this is the place where our little school holds its major fundraiser each year. Because, like the golf course, in order to exist we’ve had to learn to work with what we have, relying on the love of the community that fought to keep the golf course here and now works like mad to keep the school alive.

Two years ago the local school district shut our school. The federal government gave us money to keep it going but those monies are caught up in a bureaucratic boondoggle of epic proportions. And so we have to count on the kindness, and donations, of both friends and strangers to keep our doors open, all the while hoping for a miracle.

On the day of the golf tournament, the sun filled the sky and the scent of autumn filled the air. Then around noon, clouds moved in, bringing with them colder temperatures and worry. If it rained, would our fundraiser, with its moneymaking silent auction and BBQ, be cancelled? At 2 p.m., a call came in from Yosemite Valley—a freak storm had dumped over an inch of rain in just an hour. The Valley was flooded; restaurants and stores were closed. At 3 p.m., with storm clouds building, a roll of thunder went so long and loud that I scurried from my sixth-hole chair and headed for the safety of the Wawona Hotel. At 4 p.m., the sun returned ... only a few sprinkles had fallen on our day. I took it as a sign. Perhaps, like Kim Porter and the golf course, the school will flourish, proving the power of an audacious dream and a resilient nature. That’s a hole in one I’d like to see.

-- Jamie Simons/Photos by Jon Jay

Two years ago the local school district shut our school. The federal government gave us money to keep it going but those monies are caught up in a bureaucratic boondoggle of epic proportions. And so we have to count on the kindness, and donations, of both friends and strangers to keep our doors open, all the while hoping for a miracle.

On the day of the golf tournament, the sun filled the sky and the scent of autumn filled the air. Then around noon, clouds moved in, bringing with them colder temperatures and worry. If it rained, would our fundraiser, with its moneymaking silent auction and BBQ, be cancelled? At 2 p.m., a call came in from Yosemite Valley—a freak storm had dumped over an inch of rain in just an hour. The Valley was flooded; restaurants and stores were closed. At 3 p.m., with storm clouds building, a roll of thunder went so long and loud that I scurried from my sixth-hole chair and headed for the safety of the Wawona Hotel. At 4 p.m., the sun returned ... only a few sprinkles had fallen on our day. I took it as a sign. Perhaps, like Kim Porter and the golf course, the school will flourish, proving the power of an audacious dream and a resilient nature. That’s a hole in one I’d like to see.

-- Jamie Simons/Photos by Jon Jay

11/11/2011 Year in Yosemite: Winter? It's All Downhill From Here

There are people in this world whose entire day can be dictated by a morning ritual that starts with stepping on a scale. Numbers up? Bad, sad mood. Numbers down? The world is a wonderful place. Same for those who start each day by looking at the stock market. Numbers up? Good day. Numbers down? Not so fine. Me? Ever since we moved to Yosemite National Park, my ritual goes like this—get up, make a cup of coffee, turn on the computer and read Yosemite’s Daily Report. Put out by the park service for Yosemite employees, it always starts the same way—with the weather report. And like the scale and stock market watchers, my mood is dictated by what I read, but in the opposite way. Numbers up? I’m elated. Numbers down? My mood is bad and sad.

This being November, each day I look, the numbers are headed in the wrong direction. We live in California after all, home to palm trees, sunshine, year ‘round tans (natural and otherwise) and surfers. I don’t remember the Beach Boys crooning anything about ice, snow, hail and sleet. Yet starting about now, that’s just what Yosemite’s tiny population of year ‘rounders and its visitors can expect.

The first year we lived here, in the blush of new-found love, the winter didn’t bother me, even a ten-day power outage brought on by wet snow and blowing winds seemed romantic in a Little House on the Prairie way. (Okay, it was romantic for about the first four days, then it was just a pain). By the second year, the snow, ice and freezing temperatures were something I put up with, fairly successfully. By that time, we’d acquired a generator; two used all-wheel drive Subarus, heated mattress pads for our beds (for those lucky days when the electricity in our home actually worked), and the good sense to leave the park for warmer climes when we had another weeklong power outage.

This year, neither my husband nor myself have the stomach for winter, with its freezing temperatures, power meltdowns and dangerous driving conditions. We’re in sunny, warm Southern California as I write and the thought of going home chills us. Truth be told, we’d stay here if we could, but we’ve got a problem. We moved to Yosemite National Park more for our daughter than ourselves. At the time, we couldn’t imagine a better experience for a child than going to school in a national park. And we were right. Everything about our time in Yosemite has improved our daughter’s life. She’s happier, more adaptable and more curious. She has core values we value. And, having had to make a life in a place with few, if any, kids her age, she’s friendly, out-going and pretty accepting of kids of all ages (considering that she’s ten, and like most children, wants the world, and her friends, to fit her picture of the way things should be).

She’s also over the moon about snow. If she were in charge of the weather, winter would be ten months long. When we first came to look at Yosemite as a serious place to settle, the teacher at the local school told our daughter that she had two goals for her—to learn to love math (the bane of our daughter’s existence) and for her to become a good skier. By the end of the first year of living here, both those goals had been met. And winter, with its snow-covered hills for sledding and snow-covered mountains for skiing, had become our daughter’s favorite time of year. So we’re staying put.

There are people in this world whose entire day can be dictated by a morning ritual that starts with stepping on a scale. Numbers up? Bad, sad mood. Numbers down? The world is a wonderful place. Same for those who start each day by looking at the stock market. Numbers up? Good day. Numbers down? Not so fine. Me? Ever since we moved to Yosemite National Park, my ritual goes like this—get up, make a cup of coffee, turn on the computer and read Yosemite’s Daily Report. Put out by the park service for Yosemite employees, it always starts the same way—with the weather report. And like the scale and stock market watchers, my mood is dictated by what I read, but in the opposite way. Numbers up? I’m elated. Numbers down? My mood is bad and sad.

This being November, each day I look, the numbers are headed in the wrong direction. We live in California after all, home to palm trees, sunshine, year ‘round tans (natural and otherwise) and surfers. I don’t remember the Beach Boys crooning anything about ice, snow, hail and sleet. Yet starting about now, that’s just what Yosemite’s tiny population of year ‘rounders and its visitors can expect.

The first year we lived here, in the blush of new-found love, the winter didn’t bother me, even a ten-day power outage brought on by wet snow and blowing winds seemed romantic in a Little House on the Prairie way. (Okay, it was romantic for about the first four days, then it was just a pain). By the second year, the snow, ice and freezing temperatures were something I put up with, fairly successfully. By that time, we’d acquired a generator; two used all-wheel drive Subarus, heated mattress pads for our beds (for those lucky days when the electricity in our home actually worked), and the good sense to leave the park for warmer climes when we had another weeklong power outage.

This year, neither my husband nor myself have the stomach for winter, with its freezing temperatures, power meltdowns and dangerous driving conditions. We’re in sunny, warm Southern California as I write and the thought of going home chills us. Truth be told, we’d stay here if we could, but we’ve got a problem. We moved to Yosemite National Park more for our daughter than ourselves. At the time, we couldn’t imagine a better experience for a child than going to school in a national park. And we were right. Everything about our time in Yosemite has improved our daughter’s life. She’s happier, more adaptable and more curious. She has core values we value. And, having had to make a life in a place with few, if any, kids her age, she’s friendly, out-going and pretty accepting of kids of all ages (considering that she’s ten, and like most children, wants the world, and her friends, to fit her picture of the way things should be).

She’s also over the moon about snow. If she were in charge of the weather, winter would be ten months long. When we first came to look at Yosemite as a serious place to settle, the teacher at the local school told our daughter that she had two goals for her—to learn to love math (the bane of our daughter’s existence) and for her to become a good skier. By the end of the first year of living here, both those goals had been met. And winter, with its snow-covered hills for sledding and snow-covered mountains for skiing, had become our daughter’s favorite time of year. So we’re staying put.

One of our neighbors, a woman who has lived inside Yosemite Park for over twenty years, once told me it was the winters that broke people. If they moved away, it was the weather, more than the isolation, that drove them away. Third year in, I can believe it. I grew up in Minnesota. I know about cold and snow. I also know that I live in a state that provides a choice. Unlike major parts of America, one can live in California one’s whole life and never have to drive on ice or shovel a walk.

Still, when I’m sitting in Southern California traffic and looking out over miles and miles of seemingly mindless development, the picture I conjure up to calm my soul is not Yosemite in summer, or even spring with its wondrous waterfalls and budding growth. No, it’s a day last winter, when in a storm, we drove along roads bordered by trees so thick with snow that all color had faded to black and white by mid-day. It was, and remains, the singular most beautiful landscape I’ve ever seen. Sitting, as I do now, at the beach in Southern California, I know that’s quite a statement. But it reminds me that indulgent parents that we might be, life is often best when seen through the eyes of a child.

-- Jamie Simons/Photos by Jon Jay

Still, when I’m sitting in Southern California traffic and looking out over miles and miles of seemingly mindless development, the picture I conjure up to calm my soul is not Yosemite in summer, or even spring with its wondrous waterfalls and budding growth. No, it’s a day last winter, when in a storm, we drove along roads bordered by trees so thick with snow that all color had faded to black and white by mid-day. It was, and remains, the singular most beautiful landscape I’ve ever seen. Sitting, as I do now, at the beach in Southern California, I know that’s quite a statement. But it reminds me that indulgent parents that we might be, life is often best when seen through the eyes of a child.

-- Jamie Simons/Photos by Jon Jay

11/18/2011 Year in Yosemite: A Grand Vision

I once interviewed an artist who had been raised in Yosemite Valley from the time he was a toddler until he left for college in Manhattan. Asked how he made the transition from living in a national park to living in America's largest city, he replied, "It was easy. They remind me of each other." At the time, I chalked his comment up to an artist's sensibility. But then several more people told me that their two favorite places on Earth were Yosemite and Manhattan. Coincidence? Or something more?

Obviously both places are defined by massive walls that tower overhead (and let's face it, the Valley floor in summer feels like Manhattan at rush hour), but, that said, I couldn't help but wonder why so many people seemed to feel a connection between two places that, to me at least, seemed so different. Then I read Bill Bryson's At Home: A Short History of Private Life. There, on page 323, in a chapter called “The Garden,” I had my aha moment. Both places were heavily shaped and influenced by the vision of one man -- and that man was Frederick Law Olmstead.

In 1857, at the age of 35, Olmstead won his first commission as a landscape architect. The place was 840 acres of scrub and marshland in what was then the far reaches of Manhattan -- now known as Central Park. At the time, his only experience moving earth was as a farmer. He hadn't a clue how to draft a blueprint. But he'd witnessed the British movement away from the structured, geometric gardens of France and Italy to a more pastoral design. He wanted the same for America, only better. In Europe, parks and countryside retreats were strictly the domain of the aristocracy, the rich and the well connected. A patriotic American, Olmstead believed the government had a moral obligation to provide green space -- huge, great, massive tracts of it -- for all the people to enjoy.

I once interviewed an artist who had been raised in Yosemite Valley from the time he was a toddler until he left for college in Manhattan. Asked how he made the transition from living in a national park to living in America's largest city, he replied, "It was easy. They remind me of each other." At the time, I chalked his comment up to an artist's sensibility. But then several more people told me that their two favorite places on Earth were Yosemite and Manhattan. Coincidence? Or something more?

Obviously both places are defined by massive walls that tower overhead (and let's face it, the Valley floor in summer feels like Manhattan at rush hour), but, that said, I couldn't help but wonder why so many people seemed to feel a connection between two places that, to me at least, seemed so different. Then I read Bill Bryson's At Home: A Short History of Private Life. There, on page 323, in a chapter called “The Garden,” I had my aha moment. Both places were heavily shaped and influenced by the vision of one man -- and that man was Frederick Law Olmstead.

In 1857, at the age of 35, Olmstead won his first commission as a landscape architect. The place was 840 acres of scrub and marshland in what was then the far reaches of Manhattan -- now known as Central Park. At the time, his only experience moving earth was as a farmer. He hadn't a clue how to draft a blueprint. But he'd witnessed the British movement away from the structured, geometric gardens of France and Italy to a more pastoral design. He wanted the same for America, only better. In Europe, parks and countryside retreats were strictly the domain of the aristocracy, the rich and the well connected. A patriotic American, Olmstead believed the government had a moral obligation to provide green space -- huge, great, massive tracts of it -- for all the people to enjoy.

Teaming up with architect Calvert Vaux (who knew his way around a drafting table), Olmstead was, in Bryson's words, absolutely against anything "noisy, vigorous or fun. He especially didn't want diversions like zoos and boating lakes -- the very sorts of amusements users craved." Instead, Olmstead felt that parks should have a wildness to them in order to provide opportunity for reflection and renewal. Only then could nature act as an antidote to the crushing noise, daily stresses and overcrowding of urban life. But the "masses" for whom he'd designed Central Park didn't see things quite his way. Hence the boating lake, pavilions, skating rink and zoo that help make Central Park what it is today.

Disappointed, Olmstead accepted a job out West working for the flamboyant John and Jessie Fremont. Hired to run their mining operation in Mariposa County, he hated every moment of his stay, finding Californians to be "thriftless, fortune-hunting, improvident, gambling vagabonds." He had even worse things to say about the people we call pioneers. But he did have a solution. A park -- one done on a massive scale -- designed by heaven and Frederick Olmstead to act as a civilizing force. He called it "Yo Semite."

To accomplish this, he proposed a radical idea. Writing as the head of a commission that was to decide how the Yosemite land grant (signed into law by Abraham Lincoln in the midst of the Civil War) should be administered, Olmstead wrote that