WawonaNews.com - October 2013

Risky Measures to Save Big Trees Worked

By Diana Marcum - LA Times, September 22, 2013, 7:46 p.m.

YOSEMITE NATIONAL PARK, Calif. — Each afternoon the fire's thunderous plume rose.

At night, helicopter crews at the Crane Flat lookout watched a line of orange burning across the horizon. The line kept drawing closer.

By the last week of August, every effort to halt the Rim fire before it moved deeper into the national park had failed. The blaze now had a clear path to the Tuolumne and Merced groves of giant sequoia, and the Rockefeller grove, one of the last stands of giant sugar pine untouched by logging.

On Aug. 30, a Friday, a group of firefighters gathered at the lookout to launch a risky plan to protect some of Earth's oldest and largest living organisms.

Even Ben Jacobs, the division commander, was nervous.

Jacobs, 55, had fought wildfires and managed prescribed burns at Sequoia Kings Canyon National Park. But he had seen crews take chances earlier in the week trying to save family camps and businesses. If they'd gambled for buildings, what would they do for living giants?

He also worried that if crews lost control of the backfires they were about to ignite, flames could spread for miles, even as far as the Merced River, west of the park's famous valley.

"Listen," he said. "Nobody wants to be the guy who burned down Yosemite."

They had known a fire like this was coming.

A hundred years of fire suppression had created a buildup of trees, logs and other fuels. Fire could climb up and fly through the crowns of trees rather than burn on the ground as forest fires had for centuries. Add two years of extreme drought, and the Sierra Nevada was a pile of kindling.

Inside Yosemite, officials had tried to restore the natural cycle of fire. For 40 years, lightning-sparked flames in wilderness areas had been left to burn, and specialists lighted controlled burns near tourist areas. But that might not offer enough protection.

"Hypothetically those old fire scars would slow the fire the further it moved into the park," said Gus Smith, Yosemite's fire ecologist. "But the Rim fire was like a flood, and it was coming. This was not the fire you wanted to test out a hypothesis."

It had first been spotted in a remote area of neighboring Stanislaus National Forest.

Two days later, on Aug. 17, flames exploded over a ridge above the Tuolumne River. Whitewater rafters navigating the canyon of buckeyes and bald eagles said it sounded like bombs.

It was about 20 miles in the distance, but Yosemite Fire Chief Kelly Martin, a specialist in predicting fire behavior, knew it was headed their way.

"This is it," she said. "This is the Big One."

Now, it had pushed 30 miles inside the park, moving south toward California 120 — the main east-west route through Yosemite. In one day it had burned 50,000 acres inside the park. The biggest fire since the park began keeping records in 1930 had burned 46,000.

The sequoias evolved to face wildfire. But officials feared that this fire could kill even trees that had been shrugging off flames since before Rome burned.

Jacobs and Taro Pusina, Yosemite's deputy fire chief, drew up a plan. They would set three coordinated backfires and try to stop the wildfire with a "catcher's mitt" of charred earth.

But first they would wind the fires through two of the very groves they were trying to protect. The Tuolumne and Merced groves were at the top of a ridge, in the direct line of the Rim fire, in an area that had not burned for 100 years. If the hotter Rim fire reached them, it could climb to the tops of 200-foot trees.

A lot could go wrong. If the backfires were too hot, they could cook the groves. If they did not burn enough ground in time, the Rim fire would roar through unblocked. Those two groves and the Merced Grove to the south would burn, the lookout tower and helicopter base would burn, and the firefighters would have to run.

"We knew it was a longshot," Pusina said. "But no amount of bulldozers or planes or crews had stopped this fire. We were out of options."

They met at the lookout peak at 1:30 p.m. that Friday. The flames were two miles away — a mile closer than the day before.

They lighted a test blaze. The plants were so dry that flames shot over 50 feet high at the edge of the helipad.

"So, OK. Looks like we're going to have our hands a little bit full," said Pusina, the deputy fire chief, drawing a laugh.

Hotshot crews hiked down to the Rockefeller grove. It was purchased in 1930 with the help of a $1.7-million donation from John D. Rockefeller, saving the towering sugar pines about to be cut for timber and expanding the national park.

With a drip torch mixing three parts diesel and one part gasoline, crews started a line of fire.

"I'm not a big guy of faith," said Smith, the Yosemite fire ecologist. "But at that moment, we're committed. You just had to let go and believe that it was going to be the right thing."

Winds blew smoke and flames back, as the crew pushed the fire into thousands of acres of sugar pines, cedar and ponderosa.

"C'mon, c'mon. You have to move faster," Jacobs told them.

All through the night, the grove growled and crashed with fire.

The next day, with the first grove still burning, a handful of firefighters drove into the Tuolumne grove, a mile to the east.

A fire crew from Arizona had prepared the area — raking debris away from trees, sawing snags and logs. Many of them had never seen a giant sequoia, which is native only on the western slope of the Sierra Nevada. The species dates back to the Ice Age.

"They were in awe of the trees. They kept looking up as they worked," recalled Gary Oye, division chief of wilderness stewardship.

When Jacobs arrived, the first thing he had the Arizona crew do was pull out the sprinkler system that had been installed as a backup plan. The grove was crowded and there were few young trees. Sequoias thrive in fire as long as it does not reach their canopies. It helps cones disperse seeds and makes room for new growth.

"If we were going to do this, I wanted to know the grove was going to be here in a thousand years," Jacobs said. "I wanted to picture seedlings and saplings."

He gave drip torches to the Arizona firefighters, who would set small fires amid the massive landmark trees, then get out.

Smoke curled around the enormous trunks with red bark that hangs like candle drippings. Small fires glowed through the grove. On the ridge, hotshots laid out flames. A mile away, a super blaze kept coming.

At Crane Flat, crews lighted a fire to burn east and meet the Tuolumne blaze. By 9 p.m., the backfires linked.

There was a thin black line between the ancient trees and the Rim fire.

"It felt like a moment out of time," Oye said. "You knew these trees had seen this before and survived. Man had almost destroyed them. But this time man was trying to save them."

Pusina said he felt a sense of solace.

"I know it sounds cheesy — but I swear I could hear the trees sigh with relief. They wanted our fire," he said. "They knew the Rim fire was out there."

Smith, the fire ecologist, anxiously waited for the flames to die down so he could get to the trees. He was most concerned for the sugar pines, which nature built to resist flames. But nothing was as fireproof as a sequoia, with its soft, stringy, 2-foot-thick bark.

That Thursday, he hiked a fire line into the Rockefeller grove. Helicopters and planes buzzed overhead. The Rim fire, now the third-largest in California history, was still being fought on other fronts.

His shoulders slumped when he saw a tall cedar, cut down, a fire burning within it.

"That was my favorite cedar. It had fire in it for a long time," he said.

The ground was thick with pieces of things that once were — giant logs, young trees, craggy snags burned down to charcoal. Corkscrews of smoke rose across the landscape, bowls of stumps and fallen trees burned orange.

Smith stamped out a flame with his shovel. He bent to look at bear tracks. He fingered dogwood, some of the leaves still green and listened to the song of a nuthatch.

He studied the bottom of the trunks of burned trees. If there had been a lot of pine needles and cones piled up at the base, the fire could have ringed them with too much heat and cut off their vascular system. They would stand for now, providing shelter for birds and animals but be dead within seven years.

"You might make it," he said to a towering pine with a black ring stretching less than halfway around.

Deep in the grove, 400-year-old sugar pines still stood. There were few girdle marks.

Smith turned slowly in a half circle looking up at the fluttering green canopy hundreds of feet above. He smiled.

"Come back in the spring," he said. "This is going to be gorgeous."

YOSEMITE NATIONAL PARK, Calif. — Each afternoon the fire's thunderous plume rose.

At night, helicopter crews at the Crane Flat lookout watched a line of orange burning across the horizon. The line kept drawing closer.

By the last week of August, every effort to halt the Rim fire before it moved deeper into the national park had failed. The blaze now had a clear path to the Tuolumne and Merced groves of giant sequoia, and the Rockefeller grove, one of the last stands of giant sugar pine untouched by logging.

On Aug. 30, a Friday, a group of firefighters gathered at the lookout to launch a risky plan to protect some of Earth's oldest and largest living organisms.

Even Ben Jacobs, the division commander, was nervous.

Jacobs, 55, had fought wildfires and managed prescribed burns at Sequoia Kings Canyon National Park. But he had seen crews take chances earlier in the week trying to save family camps and businesses. If they'd gambled for buildings, what would they do for living giants?

He also worried that if crews lost control of the backfires they were about to ignite, flames could spread for miles, even as far as the Merced River, west of the park's famous valley.

"Listen," he said. "Nobody wants to be the guy who burned down Yosemite."

They had known a fire like this was coming.

A hundred years of fire suppression had created a buildup of trees, logs and other fuels. Fire could climb up and fly through the crowns of trees rather than burn on the ground as forest fires had for centuries. Add two years of extreme drought, and the Sierra Nevada was a pile of kindling.

Inside Yosemite, officials had tried to restore the natural cycle of fire. For 40 years, lightning-sparked flames in wilderness areas had been left to burn, and specialists lighted controlled burns near tourist areas. But that might not offer enough protection.

"Hypothetically those old fire scars would slow the fire the further it moved into the park," said Gus Smith, Yosemite's fire ecologist. "But the Rim fire was like a flood, and it was coming. This was not the fire you wanted to test out a hypothesis."

It had first been spotted in a remote area of neighboring Stanislaus National Forest.

Two days later, on Aug. 17, flames exploded over a ridge above the Tuolumne River. Whitewater rafters navigating the canyon of buckeyes and bald eagles said it sounded like bombs.

It was about 20 miles in the distance, but Yosemite Fire Chief Kelly Martin, a specialist in predicting fire behavior, knew it was headed their way.

"This is it," she said. "This is the Big One."

Now, it had pushed 30 miles inside the park, moving south toward California 120 — the main east-west route through Yosemite. In one day it had burned 50,000 acres inside the park. The biggest fire since the park began keeping records in 1930 had burned 46,000.

The sequoias evolved to face wildfire. But officials feared that this fire could kill even trees that had been shrugging off flames since before Rome burned.

Jacobs and Taro Pusina, Yosemite's deputy fire chief, drew up a plan. They would set three coordinated backfires and try to stop the wildfire with a "catcher's mitt" of charred earth.

But first they would wind the fires through two of the very groves they were trying to protect. The Tuolumne and Merced groves were at the top of a ridge, in the direct line of the Rim fire, in an area that had not burned for 100 years. If the hotter Rim fire reached them, it could climb to the tops of 200-foot trees.

A lot could go wrong. If the backfires were too hot, they could cook the groves. If they did not burn enough ground in time, the Rim fire would roar through unblocked. Those two groves and the Merced Grove to the south would burn, the lookout tower and helicopter base would burn, and the firefighters would have to run.

"We knew it was a longshot," Pusina said. "But no amount of bulldozers or planes or crews had stopped this fire. We were out of options."

They met at the lookout peak at 1:30 p.m. that Friday. The flames were two miles away — a mile closer than the day before.

They lighted a test blaze. The plants were so dry that flames shot over 50 feet high at the edge of the helipad.

"So, OK. Looks like we're going to have our hands a little bit full," said Pusina, the deputy fire chief, drawing a laugh.

Hotshot crews hiked down to the Rockefeller grove. It was purchased in 1930 with the help of a $1.7-million donation from John D. Rockefeller, saving the towering sugar pines about to be cut for timber and expanding the national park.

With a drip torch mixing three parts diesel and one part gasoline, crews started a line of fire.

"I'm not a big guy of faith," said Smith, the Yosemite fire ecologist. "But at that moment, we're committed. You just had to let go and believe that it was going to be the right thing."

Winds blew smoke and flames back, as the crew pushed the fire into thousands of acres of sugar pines, cedar and ponderosa.

"C'mon, c'mon. You have to move faster," Jacobs told them.

All through the night, the grove growled and crashed with fire.

The next day, with the first grove still burning, a handful of firefighters drove into the Tuolumne grove, a mile to the east.

A fire crew from Arizona had prepared the area — raking debris away from trees, sawing snags and logs. Many of them had never seen a giant sequoia, which is native only on the western slope of the Sierra Nevada. The species dates back to the Ice Age.

"They were in awe of the trees. They kept looking up as they worked," recalled Gary Oye, division chief of wilderness stewardship.

When Jacobs arrived, the first thing he had the Arizona crew do was pull out the sprinkler system that had been installed as a backup plan. The grove was crowded and there were few young trees. Sequoias thrive in fire as long as it does not reach their canopies. It helps cones disperse seeds and makes room for new growth.

"If we were going to do this, I wanted to know the grove was going to be here in a thousand years," Jacobs said. "I wanted to picture seedlings and saplings."

He gave drip torches to the Arizona firefighters, who would set small fires amid the massive landmark trees, then get out.

Smoke curled around the enormous trunks with red bark that hangs like candle drippings. Small fires glowed through the grove. On the ridge, hotshots laid out flames. A mile away, a super blaze kept coming.

At Crane Flat, crews lighted a fire to burn east and meet the Tuolumne blaze. By 9 p.m., the backfires linked.

There was a thin black line between the ancient trees and the Rim fire.

"It felt like a moment out of time," Oye said. "You knew these trees had seen this before and survived. Man had almost destroyed them. But this time man was trying to save them."

Pusina said he felt a sense of solace.

"I know it sounds cheesy — but I swear I could hear the trees sigh with relief. They wanted our fire," he said. "They knew the Rim fire was out there."

Smith, the fire ecologist, anxiously waited for the flames to die down so he could get to the trees. He was most concerned for the sugar pines, which nature built to resist flames. But nothing was as fireproof as a sequoia, with its soft, stringy, 2-foot-thick bark.

That Thursday, he hiked a fire line into the Rockefeller grove. Helicopters and planes buzzed overhead. The Rim fire, now the third-largest in California history, was still being fought on other fronts.

His shoulders slumped when he saw a tall cedar, cut down, a fire burning within it.

"That was my favorite cedar. It had fire in it for a long time," he said.

The ground was thick with pieces of things that once were — giant logs, young trees, craggy snags burned down to charcoal. Corkscrews of smoke rose across the landscape, bowls of stumps and fallen trees burned orange.

Smith stamped out a flame with his shovel. He bent to look at bear tracks. He fingered dogwood, some of the leaves still green and listened to the song of a nuthatch.

He studied the bottom of the trunks of burned trees. If there had been a lot of pine needles and cones piled up at the base, the fire could have ringed them with too much heat and cut off their vascular system. They would stand for now, providing shelter for birds and animals but be dead within seven years.

"You might make it," he said to a towering pine with a black ring stretching less than halfway around.

Deep in the grove, 400-year-old sugar pines still stood. There were few girdle marks.

Smith turned slowly in a half circle looking up at the fluttering green canopy hundreds of feet above. He smiled.

"Come back in the spring," he said. "This is going to be gorgeous."

Mariposa County Discusses Raising the Transient Occupancy Tax (TOT, Bed Tax)

On Friday, September 13, 2013 at the Government Center Board Chambers the Yosemite/Mariposa County Tourism Bureau hosted a town hall meeting that included a discussion on raising the Transient Occupancy Tax (TOT, Bed Tax). The following are excerpts from the meeting:

Mariposa County CAO Rick Benson: The Board of Supervisors (BOS) is considering increasing the TOT. Currently the rate is 10% plus a 1% BID for a total of 11%. The BOS is considering raising this to 12% plus the 1% BID for a total of 13%. This raise in TOT would increase money to the County of around $2,000,000 a year.

County Budget total of $100,000,000 for spending on county operations. $60,000,000 is not discretionary. Leaving $40,000,000 but $15,0000 of that money is also not discretionary.

BOS controls about $25,000,000. $12,500,000 is used for public protection which includes the Sheriff Department, County Jail, District Attorney's office and Probation Department. The other $12,500,000 pays for expenses including Parks and Recreation, Libraries and general operations of the county.

Overall county revenues have remained fairly stable, sales tax and property tax are down a little. TOT has been growing or maintaining through the economic downturn. The funding of $500,000 to the Tourism Bureau comes from discretionary funds. During 2012 - 2013 TOT dipped slightly from the previous year.

County costs have been going up. One cost that has been going up has been retirement benefits for county employees and the unfunded liability. Cannot cut retirement benefits due to court rulings.

Mariposa County faces level revenues but increased costs. Only two layoffs have occurred this year. County has to either increase revenue or decrease services.

Today to have a TOT increase the county has to follow Prop 218 rules. The voters get to vote on this increase. Cannot have a special election. Earliest this would probably be on the ballot would be in the fall 2014 general election.

The BOS has not made the decision whether or not to pursue raising the TOT tax. They have been discussing it.

This is an increase in taxes and an increase on costs.

TOT in other counties: Calaveras County at 6%, Fresno County at 11.4%, Madera County 9%, Merced County 10% and Tuolumne County 10%.

Before the BOS makes a decision they will have a Public Hearing and have a vote to put it on the ballot.

If they were to specifically designate what the increased funding would be spent on, the vote would have to pass by a two thirds majority instead of a 50% plus one majority.

The CAO, Rick Benson is not for specifically designating what the increased funding would be spent on.

The BOS is considering a 2% increase.

The Tourism Bureau did not initiate the raising of the TOT and the Tourism Board has taken a neutral stance on the issue.

The CAO said the money could go to infrastructure repair and roads.

On a question directed to Tourism, if they expected to receive a share in the proposed increase in TOT, Roger Biery representing the Yosemite/Mariposa County Tourism Bureau Advisory Council said it only stands to reason, if there is more money.

Public speakers that were for or against raising the TOT.

One for.

Four against.

Mariposa County CAO Rick Benson: The Board of Supervisors (BOS) is considering increasing the TOT. Currently the rate is 10% plus a 1% BID for a total of 11%. The BOS is considering raising this to 12% plus the 1% BID for a total of 13%. This raise in TOT would increase money to the County of around $2,000,000 a year.

County Budget total of $100,000,000 for spending on county operations. $60,000,000 is not discretionary. Leaving $40,000,000 but $15,0000 of that money is also not discretionary.

BOS controls about $25,000,000. $12,500,000 is used for public protection which includes the Sheriff Department, County Jail, District Attorney's office and Probation Department. The other $12,500,000 pays for expenses including Parks and Recreation, Libraries and general operations of the county.

Overall county revenues have remained fairly stable, sales tax and property tax are down a little. TOT has been growing or maintaining through the economic downturn. The funding of $500,000 to the Tourism Bureau comes from discretionary funds. During 2012 - 2013 TOT dipped slightly from the previous year.

County costs have been going up. One cost that has been going up has been retirement benefits for county employees and the unfunded liability. Cannot cut retirement benefits due to court rulings.

Mariposa County faces level revenues but increased costs. Only two layoffs have occurred this year. County has to either increase revenue or decrease services.

Today to have a TOT increase the county has to follow Prop 218 rules. The voters get to vote on this increase. Cannot have a special election. Earliest this would probably be on the ballot would be in the fall 2014 general election.

The BOS has not made the decision whether or not to pursue raising the TOT tax. They have been discussing it.

This is an increase in taxes and an increase on costs.

TOT in other counties: Calaveras County at 6%, Fresno County at 11.4%, Madera County 9%, Merced County 10% and Tuolumne County 10%.

Before the BOS makes a decision they will have a Public Hearing and have a vote to put it on the ballot.

If they were to specifically designate what the increased funding would be spent on, the vote would have to pass by a two thirds majority instead of a 50% plus one majority.

The CAO, Rick Benson is not for specifically designating what the increased funding would be spent on.

The BOS is considering a 2% increase.

The Tourism Bureau did not initiate the raising of the TOT and the Tourism Board has taken a neutral stance on the issue.

The CAO said the money could go to infrastructure repair and roads.

On a question directed to Tourism, if they expected to receive a share in the proposed increase in TOT, Roger Biery representing the Yosemite/Mariposa County Tourism Bureau Advisory Council said it only stands to reason, if there is more money.

Public speakers that were for or against raising the TOT.

One for.

Four against.

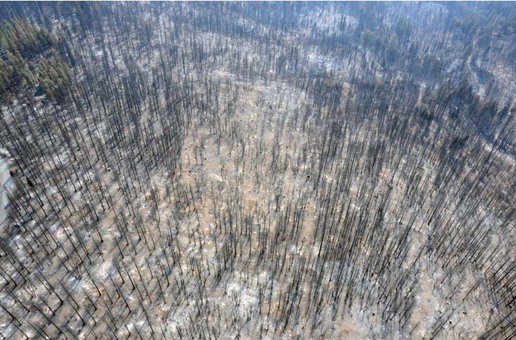

Rim Fire "Unprecedented" Destruction Leaves Barren Moonscape, but Yosemite Forests Mostly Spared

A fire that raged in forest land in and around Yosemite National Park has left a barren moonscape in the Sierra Nevada mountains that experts say is larger than any burned there in centuries.

The fire has consumed about 400 square miles, and within that footprint are a solid 60 square miles that burned so intensely that everything is dead, researchers said.

"In other words, it's nuked," said Jay Miller, senior wildland fire ecologist with the U.S. Forest Service. "If you asked most of the fire ecologists working in the Sierra Nevada, they would call this unprecedented."

Smaller pockets inside the fire's footprint also burned hot enough to wipe out trees and other vegetation.

In total, Miller estimates that almost 40 percent of the area inside the fire's boundary is nothing but charred land. Other areas that burned left trees scarred but alive.

Using satellite imagery, Miller created a map of the devastation in the wake of the third-largest wildfire in California history and the largest recorded in the Sierra Nevada.

Biologists who have mapped and studied the ages and scarring of trees throughout the mountain range have been able to determine the severity and size of fires that occurred historically.

Miller says a fire has not left such a contiguous moonscape in the Sierra since before the Little Ice Age, which began in 1350.

In the decades before humans began controlling fire in forests, the Sierra would burn every 10 to 20 years, clearing understory growth on the ground and opening up clearings for new tree growth. Modern-day practices of firesuppression, combined with cutbacks in forest service budgets and a desire to reduce smoke impacts in the polluted San Joaquin Valley, have combined to create tinderboxes, experts say.

Drought, and dryness associated with a warming climate also have contributed to the intensity of fires this year, researchers say.

"If you had a fire every 20 years, you wouldn't have many like this or you'd never have trees that were 400 years old," Miller said.

Some areas of the Stanislaus National Forest ravaged by the Rim Fire had not burned in 100 years. Most of the land that now resembles a moonscape burned on Aug. 21 and Aug. 22, when the fire jumped to canopies and was spreading the fastest.

In Yosemite National Park, where lightning fires mostly are allowed to burn out naturally and prescribed burns mimic natural conditions, the destruction was much less.

The Rim Fire has burned 77,000 acres in wilderness areas in the northeast corner of Yosemite, but only 7 percent of that area was considered high intensity that would result in tree mortality, said Chris Holbeck, a resource biologist for the National Park Service.

"It really burned here much like a prescribed fire would to a large degree because of land management practices," Holbeck said. "Fire plays a natural part of that system. It can't all be old growth forests, though Yosemite holds some of the oldest trees in the Sierra."

Short-term impacts in the park could include the displacement of a unique and threatened subspecies of great gray owls that makes home in treetops in the fire's range.

The Rim Fire started Aug. 17, when a hunter's fire spread, and continues to burn. It is named for a ridge near the location where the fire started — The Rim of the World, an overlook above a gorge carved by the Tuolumne River. The area that burned in 1987 and again in 1996 was filled with chaparral.

By the time the Rim Fire ripped through the canyon, it developed its own weather system that pushed it to consume up to 50,000 acres in a day.

The satellite was able to map only the parts of the fire where the canopy of trees was destroyed. Other areas burned closer to the ground, so it could take a year to determine whether root systems of trees outside the worst areas of destruction will die as well.

Researchers used satellites to measure the amount of chlorophyll left in canopies to determine which areas will now resemble a charred moonscape.

"We look at where the photosynthetic vegetation is killed," Miller said. "It's not a measure of the intensity of the fire but a measure of a change in the chlorophyll that is there by and large."

While the landscape has been ravaged, the soil that determines the amount of post-fire erosion that might occur when winter storms hit didn't suffer as badly as scientists feared.

Severe soil damage occurred on just 7 percent of the land inside the fire's footprint, said officials with the federal Burned Area Environmental Response team. Fire can destroy soil and make it susceptible to erosion by either burning the fine roots and other organic matter that holds it together, or by burning chaparral that releases oils that create an impervious barrier preventing rainwater from being absorbed.

"Before we can start talking about erosion, we have to figure out where the soil is damaged," said forest service soil scientist Randy Westmoreland.

The fire has consumed about 400 square miles, and within that footprint are a solid 60 square miles that burned so intensely that everything is dead, researchers said.

"In other words, it's nuked," said Jay Miller, senior wildland fire ecologist with the U.S. Forest Service. "If you asked most of the fire ecologists working in the Sierra Nevada, they would call this unprecedented."

Smaller pockets inside the fire's footprint also burned hot enough to wipe out trees and other vegetation.

In total, Miller estimates that almost 40 percent of the area inside the fire's boundary is nothing but charred land. Other areas that burned left trees scarred but alive.

Using satellite imagery, Miller created a map of the devastation in the wake of the third-largest wildfire in California history and the largest recorded in the Sierra Nevada.

Biologists who have mapped and studied the ages and scarring of trees throughout the mountain range have been able to determine the severity and size of fires that occurred historically.

Miller says a fire has not left such a contiguous moonscape in the Sierra since before the Little Ice Age, which began in 1350.

In the decades before humans began controlling fire in forests, the Sierra would burn every 10 to 20 years, clearing understory growth on the ground and opening up clearings for new tree growth. Modern-day practices of firesuppression, combined with cutbacks in forest service budgets and a desire to reduce smoke impacts in the polluted San Joaquin Valley, have combined to create tinderboxes, experts say.

Drought, and dryness associated with a warming climate also have contributed to the intensity of fires this year, researchers say.

"If you had a fire every 20 years, you wouldn't have many like this or you'd never have trees that were 400 years old," Miller said.

Some areas of the Stanislaus National Forest ravaged by the Rim Fire had not burned in 100 years. Most of the land that now resembles a moonscape burned on Aug. 21 and Aug. 22, when the fire jumped to canopies and was spreading the fastest.

In Yosemite National Park, where lightning fires mostly are allowed to burn out naturally and prescribed burns mimic natural conditions, the destruction was much less.

The Rim Fire has burned 77,000 acres in wilderness areas in the northeast corner of Yosemite, but only 7 percent of that area was considered high intensity that would result in tree mortality, said Chris Holbeck, a resource biologist for the National Park Service.

"It really burned here much like a prescribed fire would to a large degree because of land management practices," Holbeck said. "Fire plays a natural part of that system. It can't all be old growth forests, though Yosemite holds some of the oldest trees in the Sierra."

Short-term impacts in the park could include the displacement of a unique and threatened subspecies of great gray owls that makes home in treetops in the fire's range.

The Rim Fire started Aug. 17, when a hunter's fire spread, and continues to burn. It is named for a ridge near the location where the fire started — The Rim of the World, an overlook above a gorge carved by the Tuolumne River. The area that burned in 1987 and again in 1996 was filled with chaparral.

By the time the Rim Fire ripped through the canyon, it developed its own weather system that pushed it to consume up to 50,000 acres in a day.

The satellite was able to map only the parts of the fire where the canopy of trees was destroyed. Other areas burned closer to the ground, so it could take a year to determine whether root systems of trees outside the worst areas of destruction will die as well.

Researchers used satellites to measure the amount of chlorophyll left in canopies to determine which areas will now resemble a charred moonscape.

"We look at where the photosynthetic vegetation is killed," Miller said. "It's not a measure of the intensity of the fire but a measure of a change in the chlorophyll that is there by and large."

While the landscape has been ravaged, the soil that determines the amount of post-fire erosion that might occur when winter storms hit didn't suffer as badly as scientists feared.

Severe soil damage occurred on just 7 percent of the land inside the fire's footprint, said officials with the federal Burned Area Environmental Response team. Fire can destroy soil and make it susceptible to erosion by either burning the fine roots and other organic matter that holds it together, or by burning chaparral that releases oils that create an impervious barrier preventing rainwater from being absorbed.

"Before we can start talking about erosion, we have to figure out where the soil is damaged," said forest service soil scientist Randy Westmoreland.

Slackline Girls Talk About Their Sport

Highliners Emily Sukiennik and Libby Sauter -- the Slackline Girls -- to talk about their sport, its safety, how they've developed their skills, and their next challenge. Video footage shows the same spot on The Fissures which Jake Baker used earlier this week (see video below).

STATE ROUTE 120 (Tioga) Reopens

Tioga Road opens to through traffic at Noon on Saturday, September 14

SR-120 (Tioga Road) which had been closed from Crane Flat to White Wolf, within Yosemite National Park, will reopen to all vehicular traffic at noon, Saturday, September 14, 2013.

Visitors will have access to Yosemite Valley from Highway 395 via SR-120. However, due to continued fire activity in the area, stopping along the roadway is strictly prohibited. The public is advised to use extreme caution as firefighting activities continue in the area and visibility may be reduced due to smoke. For current road conditions in the park visit: http://www.nps.gov/yose/planyourvisit/traffic.htm.

Current road conditions can also be found at Caltrans’ website: www.dot.ca.gov/

or by calling Caltrans District 10 Public Affairs Office at (209) 948-7977. The area burned by the Rim Fire within Yosemite National Park remains closed due to hazardous conditions.

Rim Fire Stanislaus National Forest closures remain in effect. For forest closure information visit www.fs.usda.gov/stanislaus

Amazing Feet (and Feat)

Tightrope walker Jake Baker walked the width of one of the Fissures this morning near Taft Point. Jake prepared his equipment for a period of one hour prior to his walk. This included hanging from the rope at different intervals while he applied tape to the two ropes he set up. Click on the video to watch Jake walk across the Fissure and then click on the images below to enlarge them.

Rim Fire Grows Over Weekend: Still 80% Contained

L.A. Times

By Jason Wells and Joseph Serna September 9, 2013, 9:45 a.m.

The massive Rim fire in and around Yosemite National Park remains 80% contained after growing in size over the weekend.

Firefighters on Monday face hot, extremely dry conditions that, combined with shifting winds and low humidity, can make for “active fire behavior,” according to the U.S. Forest Service.

The Rim fire — the third-largest fire in California history — has so far cost $96.2 million to fight after erupting in the Stanislaus National Forest on Aug. 17. It has destroyed 11 homes and 97 outbuildings, according to the Forest Service.

On Monday, there were more than 3,100 personnel assigned to the blaze.

Officials said they expected the Rim fire — started by a hunter who lost control of his campfire — to intensify as flames burn through remaining vegetation within its interior.

Authorities opened the western section of California 120 into Yosemite National Park on Friday, giving visitors full access to Yosemite Valley from the park's western entrance from Groveland for the first time since the Rim fire broke out.

A 14-mile stretch of the highway remained closed within the park, from Crane Flat to White Wolf.

The top priority for firefighters was containing spot fires, particularly along Tioga Road, according to an incident update from the Forest Service. Firefighters also planned to monitor the site of a four-acre blaze near Long Barn that was fully contained Sunday.

Cal Fire crews have shored up heavy defenses along the Rim fire's northern and western faces, from Pinecrest to Groveland, eliminating the threat to thousands of homes.

By Jason Wells and Joseph Serna September 9, 2013, 9:45 a.m.

The massive Rim fire in and around Yosemite National Park remains 80% contained after growing in size over the weekend.

Firefighters on Monday face hot, extremely dry conditions that, combined with shifting winds and low humidity, can make for “active fire behavior,” according to the U.S. Forest Service.

The Rim fire — the third-largest fire in California history — has so far cost $96.2 million to fight after erupting in the Stanislaus National Forest on Aug. 17. It has destroyed 11 homes and 97 outbuildings, according to the Forest Service.

On Monday, there were more than 3,100 personnel assigned to the blaze.

Officials said they expected the Rim fire — started by a hunter who lost control of his campfire — to intensify as flames burn through remaining vegetation within its interior.

Authorities opened the western section of California 120 into Yosemite National Park on Friday, giving visitors full access to Yosemite Valley from the park's western entrance from Groveland for the first time since the Rim fire broke out.

A 14-mile stretch of the highway remained closed within the park, from Crane Flat to White Wolf.

The top priority for firefighters was containing spot fires, particularly along Tioga Road, according to an incident update from the Forest Service. Firefighters also planned to monitor the site of a four-acre blaze near Long Barn that was fully contained Sunday.

Cal Fire crews have shored up heavy defenses along the Rim fire's northern and western faces, from Pinecrest to Groveland, eliminating the threat to thousands of homes.

Yosemite Conservancy Photo of the Week!

Wow! Wawona photographer Nancy Robbins captured this stunning image of the Milky Way over the Rim Fire in Yosemite National Park. You can view more of Nancy's beautiful photography by accessing her website:

www.robbinsphotography.com

www.robbinsphotography.com

Rim Fire burns into fourth week

By TRACIE CONE | Associated Press – 5 p.m. September 7, 2013

SACRAMENTO, Calif. (AP) — As a gigantic wildfire in and around Yosemite National Park entered its fourth week Saturday, environmental scientists moved in to begin assessing the damage and protecting habitat and waterways before the fall rainy season.

Members of the federal Burned Area Emergency Response team were hiking the rugged Sierra Nevada terrain even as thousands of firefighters still were battling the blaze, now the third-largest wildfire in modern California history.

Federal officials have amassed a team of 50 scientists, more than twice what is usually deployed to assess wildfire damage. With so many people assigned to the job, they hope to have a preliminary report ready in two weeks so remediation can start before the first storms, Alex Janicki, the Stanislaus National Forest BAER response coordinator, said.

Team members are working to identify areas at the highest risk for erosion into streams, the Tuolumne River and the Hetch Hetchy Reservoir, San Francisco's famously pure water supply.

The wildfire started in the Stanislaus National Forest on Aug. 17 when a hunter's illegal fire swept out of control and has burned 394 square miles of timber, meadows and sensitive wildlife habitat.

It has cost more than $89 million to fight, and officials say it will cost tens of millions of dollars more to repair the environmental damage alone.

About 5 square miles of the burned area is in the watershed of the municipal reservoir serving 2.8 million people - the only one in a national park.

"That's 5 square miles of watershed with very steep slopes," Janicki said "We are going to need some engineering to protect them."

So far the water remains clear despite falling ash, and the city water utility has a six month supply in reservoirs closer to the Bay Area.

The BAER team will be made up of hydrologists, botanists, archeologists, biologists, geologists and soil scientists from the U.S. Forest Service, Yosemite National Park, the Natural Resource Conservation and the U.S. Geological Survey.

The team also will look at potential for erosion and mudslides across the burn area, assess what's in the path and determine what most needs protecting.

"We're looking to evaluate what the potential is for flooding across the burned area," said Alan Gallegos, a team member and geologist with the Sierra National Forest. "We evaluate the potential for hazard and look at what's at risk -- life, property, cultural resources, species habitat. Then we come up with a list of treatments."

In key areas with a high potential for erosion ecologists can dig ditches to divert water, plant native trees and grasses, and spray costly hydro-mulch across steep canyon walls in the most critical places.

Fire officials still have not released the name of the hunter responsible for starting the blaze. On Friday Kent Delbon, the lead investigator, would not characterize what kind of fire the hunter had set or how they had identified the suspect.

"I can say some really good detective work out there made this thing happen," he told the Associated Press.

Delbon said the Forest Service announced the cause of the fire before being able to release details in order to end rumors started by a local fire chief that the blaze ignited in an illegal marijuana garden.

Wawona Tunnel Repairs Begin Sept. 8

Wawona Tunnel Repairs September 8 - December 13, 2013 Sunday nights 8:30 pm - Friday afternoons at 4:30 pm (no work between Friday evening and Sunday evening)

You should expect the following delays as you are traveling along the Wawona Road:

Crews will be working with controlled traffic and pilot car operations, so please be cautious and patient as you are traveling through the work zone.

You should expect the following delays as you are traveling along the Wawona Road:

- September 8 - 29, 2013: 8:00 pm - 6:00 am = 30 minute delays; 6:00 am - 8:00 pm = 15 minute delays

- September 30 - December 13, 2013: 8:00 pm - 10:00 pm = 30 minute delays; 10:00 pm - 6:00 am = 2 hour delays; 6:00 am - 8:00 pm = 15 minute delays

Crews will be working with controlled traffic and pilot car operations, so please be cautious and patient as you are traveling through the work zone.

State Route 120 from Groveland to Yosemite National Park to Reopen Today - Sept. 6

Road opens at Noon on Friday, September 6

State Route 120 (SR-120) from Groveland, CA into Yosemite National Park will reopen to all vehicular traffic at noon, Friday, September 6, 2013.

Visitors will have full access to Yosemite Valley via SR-120. However, due to continued fire activity in the area stopping along the roadway is strictly prohibited. The public is advised to use extreme caution as firefighting activities continue in this area.

Cherry Lake Road, Evergreen Road, Old Yosemite Road, Harden Flat and all other secondary roads and trailheads off of SR-120 remain closed.

SR-120 (Tioga Road) remains closed from Crane Flat to White Wolf within Yosemite National Park. Park visitors can access the Toulumne Meadows area from SR-395 via the parks east entrance at Tioga Pass.

For updated road conditions and information visit Caltrans’ website: www.dot.ca.gov/ or call Caltrans District 10 Public Affairs Office at (209) 948-7977.

Forest closures remain in effect for the Stanislaus National Forest within the Rim Fire incident perimeter. For closure information visit www.fs.usda.gov/stanislaus (S. Gediman)

State Route 120 (SR-120) from Groveland, CA into Yosemite National Park will reopen to all vehicular traffic at noon, Friday, September 6, 2013.

Visitors will have full access to Yosemite Valley via SR-120. However, due to continued fire activity in the area stopping along the roadway is strictly prohibited. The public is advised to use extreme caution as firefighting activities continue in this area.

Cherry Lake Road, Evergreen Road, Old Yosemite Road, Harden Flat and all other secondary roads and trailheads off of SR-120 remain closed.

SR-120 (Tioga Road) remains closed from Crane Flat to White Wolf within Yosemite National Park. Park visitors can access the Toulumne Meadows area from SR-395 via the parks east entrance at Tioga Pass.

For updated road conditions and information visit Caltrans’ website: www.dot.ca.gov/ or call Caltrans District 10 Public Affairs Office at (209) 948-7977.

Forest closures remain in effect for the Stanislaus National Forest within the Rim Fire incident perimeter. For closure information visit www.fs.usda.gov/stanislaus (S. Gediman)

Hunter Caused Rim Fire, U.S. Forest Service Says

AP/ September 5, 2013, 12:59 PM

A gigantic wildfire in and around Yosemite National Park was caused by an illegal fire set by a hunter, the U.S. Forest Service said Thursday. The agency said there is no indication the hunter was involved with illegal marijuana cultivation, which a local fire chief had speculated as the possible cause of the blaze.

No arrests have been made, and the hunter's name was being withheld pending further investigation, according to the Forest Service.

A Forest Service statement gave no details on how the illegal fire escaped the hunter's control.

The Rim Fire began on Aug. 17 in an isolated area of the Stanislaus National Forest and has burned nearly 371 square miles — one of the largest wildfires in California history.

Officials said 111 structures, including 11 homes, have been destroyed. Thousands of firefighters were called in to battle the blaze, which at one point threatened more than 4,000 structures,

The blaze is now 80 percent contained.

Chief Todd McNeal of the Twain Harte Fire Department told a community group recently that there was no lightning in the area, so the fire must have been caused by humans. He said he suspected it might have caused by an illicit marijuana growing operation.

But the U.S Forest Service said on Thursday no marijuana cultivation sites were located near the origin of the fire.

California's largest fire on record, a 2003 blaze in the Cleveland National Forest east of San Diego, was sparked by a novice deer hunter who became lost and set a signal fire in hope of being rescued.

Sergio Martinez was sentenced to six months in a work-furlough program, 960 hours of community service and five years of probation in 2005.

The so-called Cedar Fire burned nearly 430 square miles, caused 15 deaths and destroyed more than 2,200 homes.

A gigantic wildfire in and around Yosemite National Park was caused by an illegal fire set by a hunter, the U.S. Forest Service said Thursday. The agency said there is no indication the hunter was involved with illegal marijuana cultivation, which a local fire chief had speculated as the possible cause of the blaze.

No arrests have been made, and the hunter's name was being withheld pending further investigation, according to the Forest Service.

A Forest Service statement gave no details on how the illegal fire escaped the hunter's control.

The Rim Fire began on Aug. 17 in an isolated area of the Stanislaus National Forest and has burned nearly 371 square miles — one of the largest wildfires in California history.

Officials said 111 structures, including 11 homes, have been destroyed. Thousands of firefighters were called in to battle the blaze, which at one point threatened more than 4,000 structures,

The blaze is now 80 percent contained.

Chief Todd McNeal of the Twain Harte Fire Department told a community group recently that there was no lightning in the area, so the fire must have been caused by humans. He said he suspected it might have caused by an illicit marijuana growing operation.

But the U.S Forest Service said on Thursday no marijuana cultivation sites were located near the origin of the fire.

California's largest fire on record, a 2003 blaze in the Cleveland National Forest east of San Diego, was sparked by a novice deer hunter who became lost and set a signal fire in hope of being rescued.

Sergio Martinez was sentenced to six months in a work-furlough program, 960 hours of community service and five years of probation in 2005.

The so-called Cedar Fire burned nearly 430 square miles, caused 15 deaths and destroyed more than 2,200 homes.

What it Has Taken To Fight The Rim Fire

Rim Fire Fact Sheet

3 September 2013

Day 17

Acreage: 235,841 Square miles: 368.5

Largest wildfire in the United States to date in 2013

(Second largest to date in 2013: Lime Hills Fire, Alaska -- 201,809 acres)

No. 1-ranked on national wildland firefighting priority list

Fourth largest California wildfire in historical records dating to 1932

The four largest California wildfires have all occurred since 2003

Personnel currently on incident: 4,359

States that have sent firefighters or other personnel: 44 and the District of Columbia

Cal Fire geographical units that have sent personnel: 20 of 21

Inmate personnel from the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation: 746

Proportion of inmate personnel working on the fire: 17.1 percent

Completed containment line: 110.7 miles

Completed dozer line: 149.7 miles

Hand line: 9.3 miles Road Used as Line: 19.9 miles

Total acres burned in California to date in 2013: 493,627

Rim Fire acres as a proportion of burned acres in California: 47.8 percent

Total aviation hours: 1,543

Water dropped: 2.0 million gallons Fire retardant dropped: 2.3 million gallons

Acreage in Yosemite National Park: 66,155

Proportion of the fire burning in Yosemite National Park: 28 percent

Proportion of Yosemite National Park within the fire perimeter: 8.7 percent

Size of the fire area:

More than five times the size of Washington, D.C.

Hot meals served:

Breakfasts: 45,133 Dinners: 41,558

Pounds of firefighter laundry washed:14,148.3

Origin of Rim Fire name:

The fire started near a scenic overlook in Stanislaus National Forest called “Rim of the World”

3 September 2013

Day 17

Acreage: 235,841 Square miles: 368.5

Largest wildfire in the United States to date in 2013

(Second largest to date in 2013: Lime Hills Fire, Alaska -- 201,809 acres)

No. 1-ranked on national wildland firefighting priority list

Fourth largest California wildfire in historical records dating to 1932

The four largest California wildfires have all occurred since 2003

Personnel currently on incident: 4,359

States that have sent firefighters or other personnel: 44 and the District of Columbia

Cal Fire geographical units that have sent personnel: 20 of 21

Inmate personnel from the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation: 746

Proportion of inmate personnel working on the fire: 17.1 percent

Completed containment line: 110.7 miles

Completed dozer line: 149.7 miles

Hand line: 9.3 miles Road Used as Line: 19.9 miles

Total acres burned in California to date in 2013: 493,627

Rim Fire acres as a proportion of burned acres in California: 47.8 percent

Total aviation hours: 1,543

Water dropped: 2.0 million gallons Fire retardant dropped: 2.3 million gallons

Acreage in Yosemite National Park: 66,155

Proportion of the fire burning in Yosemite National Park: 28 percent

Proportion of Yosemite National Park within the fire perimeter: 8.7 percent

Size of the fire area:

More than five times the size of Washington, D.C.

Hot meals served:

Breakfasts: 45,133 Dinners: 41,558

Pounds of firefighter laundry washed:14,148.3

Origin of Rim Fire name:

The fire started near a scenic overlook in Stanislaus National Forest called “Rim of the World”